“It's hard for me because I am a very impatient person and I want things to change; I want things to get done. I worry a lot about what I am expressing outwardly when I embody those things too, especially as an East Asian woman too.”

she/her

This transcript has been edited for claritye.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This Is Tonia Sing Chi, and I'm here with Jenn Low for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora.

I would love it if you would tell me about how your identity as Chinese has played a role in your experience growing up. What was your family home like? Did you grow up around other Chinese or immigrant families?

Jenn Low (JL): Thanks. So my Chinese identity growing up was a little bit of a mixed bag. I am from Seattle, Washington, the suburbs in a town called Issaquah, Washington. I was born and raised there. I have two significantly older sisters. So my sisters, Teresa and Sandra, are eleven and thirteen years older than me. Teresa is actually Canadian; she was born in Canada. (laughs)

My parents were married up in British Columbia, and then subsequently, they went to Seattle, had Sandra, and then I came much, much later in the family. As a result, too, I had a sister that had passed away. So it was also this need to just recover, grieve, and then build the family too. I have very strongly identifying immigrant parents. They came from China, to Canada, to Seattle.

That influence was always like I knew that I was Chinese. I didn't understand my identity being a kid that lived in America. It was very much like an inside-outside experience. I understood who I was inside my home vaguely, but kind of just also knew that I was just a different kid. Growing up I didn't actually know how to speak Cantonese like my parents did. And then the rest of my extended family who is Chinese Canadian—everyone speaks fluent Cantonese. It was a much more culturally Chinese community and sort of existence and immersion for the remainder of my extended family. I think me and my sisters felt a little bit detached from that. Besides visits, going to birthdays and baby showers and my grandma's birthday, it was always like an in-and-out space for me. So it was very confusing because we basically grew up in a predominantly white, suburban neighborhood outside of Seattle. So being different there and then also being different within my own family was very shaping. I didn't know how to articulate that besides just feeling generally awkward for most of my childhood. So adolescence was always just trying to unpack on that aspect of my identity.

TSC: Do you think there was a reason why, when your parents moved to Issaquah, Washington, that they didn’t share your language or maybe as much of your culture with you and your siblings?

JL: It was a very distinct experience. So when my family moved to Seattle, they were living in the Green Lake, Fremont neighborhood. It’s a pretty nice neighborhood now. And my sisters grew up in the Seattle School District, and they were reprimanded. So it was like the early seventies probably. So the fact that my mom hadn't taught my sisters English—it was actually a pretty traumatic experience because the teachers basically berated my mom that my sisters couldn't speak English. ESL didn't exist back then. So, because of that whole experience, she was just led to believe, "I shouldn't actually teach you Chinese because we live here now. And for you to be able to be successful in school, I'm not going to have you go through the same things that your sisters went through." So even thatis very distinct—my sisters can actually translate for me, but they can't speak it anymore, which is so fascinating to me. But then I can't speak it.

TSC: Wow. Thank you for sharing that experience. I had a feeling that it was an intentional decision on your parent’s part, and that it wasn't just by accident or by negligence.

JL: Yeah!

TSC: Growing up, did you maintain any sort of connection with the parts of China that your family is from? Or did you feel that there was more of a break from that history?

JL: It was a pretty clear break and something that I wasn't inquisitive about. I don't remember being as a child—I think I was much more conscious of my Chinese Canadian family because we had a really big family both on my mom and dad's side. That history was fairly long because I do have older parents. They're both in their—my dad's in his later eighties; my mom is approaching eighty. So I had a curiosity specifically for my grandfathers because they had passed away at a younger age and I never knew them. So there was a lot about our history and our family that I would ask questions about through that aspect of just not knowing that family history and me being so much younger in the family—it just felt like there was so much that happened before I came into existence.

Then my mom, I think significantly, was always talking about her childhood in Hong Kong. So I'd get fun stories because my mom is very sort of, like, maker-y. She's a seamstress, and she has much more vivid memories about getting paid a penny sewing little things. She would take them home. But I mean, it's a very specific anecdote she would give me of her childhood because she had five siblings in Hong Kong living in a city. She was much more illustrative about those experiences, and my dad was much quieter. So it was like, I really didn't have that facet in my brain. So it was mostly kind of the Hong Kong life that she had that was—more because she likes to reminisce and just kind of talk about her siblings.

TSC: You talk about growing up in a very white area as a Chinese immigrant family—were there spaces that you did see yourself and your culturally mixed experiences reflected? Were there moments in your childhood where you went places and felt like, Oh, I see myself in this?

JL: I think growing up I did find that all of us Black, Brown, and Asian kids kind of gravitated to each other. There was very few of us around, but it just felt really familial. From the ages of five to before pre-teen, that's just how it was before I understood socialness or hierarchies that existed in public schools and/or middle school and being a teenager. So, again, I didn't have words to it, I think, growing up, but we did have an okay population of, like, Asian American—not specifically Chinese or Japanese, but we just had Asian Americans in my neighborhood. We had Black friends in our neighborhood. There was only a few of them, but we just kind of found each other on a corner in a neighborhood and would just hang out when we were super little. So that just felt familiar for very probably subconscious reasons. But that's where I felt, like, okay with friends, and curating my own communities became sort of like a facet about my environments that I was very much in tune to because it was harder—either family life or being in the classroom or something.

TSC: I love that. Do you feel like it was more of a coming together and creating a community around difference? Or do you think there were similarities in your familial or cultural upbringing with other Black and Brown and Asian kids?

JL: I think maybe because we also knew each other's families. I think we gravitated to each other because our parents were all sort of very much in the picture when we’d go to each other's houses. I would say also I come from a very white suburban, upper middle class—I think it's now much more upper middle-class neighborhood. Religion was, like, a binding thing, and I wasn't religious. I didn't go to a Christian Church. Mormon Church was a predominant space, and those were predominantly white spaces. So it was a different type of ecosystem that was built. But I think it was, like, an extension of the families because we had our friends as peers, but we knew that—my friend, Shaunda, had her older sister, and we knew her and hermother. Jeannie, I knew her mom because she was always around. So there was just fluid family spaces that felt a little bit comfier and safer because of that.

TSC: What is your relationship to the word Asian? I know you wrote that you identify as Asian in the questionnaire. I'm just curious how you feel about that term, how you feel about being racialized as Asian. Do you feel that that label or identity empowers or limits you in any way?

JL: It has been hard. I think Asian Americans specifically—I have felt really empowered. And I think it has been more in adulthood where I've come to understand what that identity means in terms of me feeling like there's a sense of identity and belonging with this space in between. When I started to partner with the 1882 Foundation, most of the people in that group are between the ages of seventy to ninety years old, and they're all in the East Coast—Asian American, Chinese American men that have lived in the DC area, Virginia area for a very long time since they immigrated with their families. So, fundamentally, I was like, There was nothing that I would find that probably would be connected.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This Is Tonia Sing Chi, and I'm here with Jenn Low for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora.

I would love it if you would tell me about how your identity as Chinese has played a role in your experience growing up. What was your family home like? Did you grow up around other Chinese or immigrant families?

Jenn Low (JL): Thanks. So my Chinese identity growing up was a little bit of a mixed bag. I am from Seattle, Washington, the suburbs in a town called Issaquah, Washington. I was born and raised there. I have two significantly older sisters. So my sisters, Teresa and Sandra, are eleven and thirteen years older than me. Teresa is actually Canadian; she was born in Canada. (laughs)

My parents were married up in British Columbia, and then subsequently, they went to Seattle, had Sandra, and then I came much, much later in the family. As a result, too, I had a sister that had passed away. So it was also this need to just recover, grieve, and then build the family too. I have very strongly identifying immigrant parents. They came from China, to Canada, to Seattle.

That influence was always like I knew that I was Chinese. I didn't understand my identity being a kid that lived in America. It was very much like an inside-outside experience. I understood who I was inside my home vaguely, but kind of just also knew that I was just a different kid. Growing up I didn't actually know how to speak Cantonese like my parents did. And then the rest of my extended family who is Chinese Canadian—everyone speaks fluent Cantonese. It was a much more culturally Chinese community and sort of existence and immersion for the remainder of my extended family. I think me and my sisters felt a little bit detached from that. Besides visits, going to birthdays and baby showers and my grandma's birthday, it was always like an in-and-out space for me. So it was very confusing because we basically grew up in a predominantly white, suburban neighborhood outside of Seattle. So being different there and then also being different within my own family was very shaping. I didn't know how to articulate that besides just feeling generally awkward for most of my childhood. So adolescence was always just trying to unpack on that aspect of my identity.

TSC: Do you think there was a reason why, when your parents moved to Issaquah, Washington, that they didn’t share your language or maybe as much of your culture with you and your siblings?

JL: It was a very distinct experience. So when my family moved to Seattle, they were living in the Green Lake, Fremont neighborhood. It’s a pretty nice neighborhood now. And my sisters grew up in the Seattle School District, and they were reprimanded. So it was like the early seventies probably. So the fact that my mom hadn't taught my sisters English—it was actually a pretty traumatic experience because the teachers basically berated my mom that my sisters couldn't speak English. ESL didn't exist back then. So, because of that whole experience, she was just led to believe, "I shouldn't actually teach you Chinese because we live here now. And for you to be able to be successful in school, I'm not going to have you go through the same things that your sisters went through." So even thatis very distinct—my sisters can actually translate for me, but they can't speak it anymore, which is so fascinating to me. But then I can't speak it.

TSC: Wow. Thank you for sharing that experience. I had a feeling that it was an intentional decision on your parent’s part, and that it wasn't just by accident or by negligence.

JL: Yeah!

TSC: Growing up, did you maintain any sort of connection with the parts of China that your family is from? Or did you feel that there was more of a break from that history?

JL: It was a pretty clear break and something that I wasn't inquisitive about. I don't remember being as a child—I think I was much more conscious of my Chinese Canadian family because we had a really big family both on my mom and dad's side. That history was fairly long because I do have older parents. They're both in their—my dad's in his later eighties; my mom is approaching eighty. So I had a curiosity specifically for my grandfathers because they had passed away at a younger age and I never knew them. So there was a lot about our history and our family that I would ask questions about through that aspect of just not knowing that family history and me being so much younger in the family—it just felt like there was so much that happened before I came into existence.

Then my mom, I think significantly, was always talking about her childhood in Hong Kong. So I'd get fun stories because my mom is very sort of, like, maker-y. She's a seamstress, and she has much more vivid memories about getting paid a penny sewing little things. She would take them home. But I mean, it's a very specific anecdote she would give me of her childhood because she had five siblings in Hong Kong living in a city. She was much more illustrative about those experiences, and my dad was much quieter. So it was like, I really didn't have that facet in my brain. So it was mostly kind of the Hong Kong life that she had that was—more because she likes to reminisce and just kind of talk about her siblings.

TSC: You talk about growing up in a very white area as a Chinese immigrant family—were there spaces that you did see yourself and your culturally mixed experiences reflected? Were there moments in your childhood where you went places and felt like, Oh, I see myself in this?

JL: I think growing up I did find that all of us Black, Brown, and Asian kids kind of gravitated to each other. There was very few of us around, but it just felt really familial. From the ages of five to before pre-teen, that's just how it was before I understood socialness or hierarchies that existed in public schools and/or middle school and being a teenager. So, again, I didn't have words to it, I think, growing up, but we did have an okay population of, like, Asian American—not specifically Chinese or Japanese, but we just had Asian Americans in my neighborhood. We had Black friends in our neighborhood. There was only a few of them, but we just kind of found each other on a corner in a neighborhood and would just hang out when we were super little. So that just felt familiar for very probably subconscious reasons. But that's where I felt, like, okay with friends, and curating my own communities became sort of like a facet about my environments that I was very much in tune to because it was harder—either family life or being in the classroom or something.

TSC: I love that. Do you feel like it was more of a coming together and creating a community around difference? Or do you think there were similarities in your familial or cultural upbringing with other Black and Brown and Asian kids?

JL: I think maybe because we also knew each other's families. I think we gravitated to each other because our parents were all sort of very much in the picture when we’d go to each other's houses. I would say also I come from a very white suburban, upper middle class—I think it's now much more upper middle-class neighborhood. Religion was, like, a binding thing, and I wasn't religious. I didn't go to a Christian Church. Mormon Church was a predominant space, and those were predominantly white spaces. So it was a different type of ecosystem that was built. But I think it was, like, an extension of the families because we had our friends as peers, but we knew that—my friend, Shaunda, had her older sister, and we knew her and hermother. Jeannie, I knew her mom because she was always around. So there was just fluid family spaces that felt a little bit comfier and safer because of that.

TSC: What is your relationship to the word Asian? I know you wrote that you identify as Asian in the questionnaire. I'm just curious how you feel about that term, how you feel about being racialized as Asian. Do you feel that that label or identity empowers or limits you in any way?

JL: It has been hard. I think Asian Americans specifically—I have felt really empowered. And I think it has been more in adulthood where I've come to understand what that identity means in terms of me feeling like there's a sense of identity and belonging with this space in between. When I started to partner with the 1882 Foundation, most of the people in that group are between the ages of seventy to ninety years old, and they're all in the East Coast—Asian American, Chinese American men that have lived in the DC area, Virginia area for a very long time since they immigrated with their families. So, fundamentally, I was like, There was nothing that I would find that probably would be connected.

Interview Segment:

It’s a hard thing to shake off

INTERVIEW 12 DETAILS

Narrator:

Jenn Low, she/her

Interview Date:

July 9, 2023

Keywords:

Themes: Asian American identity, Chinese identity, Cantonese, language loss, landscape architecture, design research, model minority, participatory art, public history, community history, humanities, equity, design justice, everyday life

Places: Canada, Green Lake, Fremont, Seattle, Issaquah, Washington, DC, Hong Kong, Chinatown DC, University of Washington, University of Michigan, Carleton University

References: Emergent Strategy, Adrienne Maree Brown, 1882 Foundation, Ted Gong, Harry Chow, Sojin Kim, The W.O.W. Project, Rosten Woo, Dear Chinatown DC, Dark Matter U, The Urban Studio, Justin Garrett Moore, Bryan Lee Jr, Colloqate

ABOUT JENN

Ancestral Land:

Hong Kong and Guangzhou, China*

*That I know of so far. On my mother’s side, I’m still learning more about my grandfather’s side of the family that may actually extend my ancestry outside of mainland China (new information since we had this interview).

Homeland:

Sammamish Band of the Duwamish and Snoqualmie Land (Issaquah, Washington)

Current Land:

Nacotchtank and the Piscataway Land (Washington, DC)

Diaspora Story:

My parents migrated together to the US around the early to mid-1970s by way of Vancouver and Penticton, British Columbia, Canada. This was before I was born.

Creative Fields:

Design research (qualitative), community research, landscape architecture, urban design, participatory design

Racial Justice Affiliations:

1882 Foundation, Dark Matter U, The Urban Studio, Openbox

Favorite Fruit:

Mango and oranges

Biography:

Jenn is an integrative designer, educator, and landscape

architect with over 18 years of experience in the planning and design of public

spaces. Jenn is interested in the intersection of human-centered design and the

built environment and sees both design research and the power of place as key

tools to advance our work toward justice and equity. As work in the public

realm becomes increasingly more complex, Jenn’s work aims to push for more

holistic and collaborative methods of design practice.

︎ jennwlow.com

But

hearing one gentleman—his name is Harry Chow, and he ended up documenting his whole teens and

twenties in the Shaw neighborhood in Chinatown when he was a kid through

photography. He kind of unpacked—this is the first time I met 1882 Foundation—was through this little

tour he gave of Chinatown. We just went through all his photos of him growing

up, and he was unpacking his identity of being in this in-between. He was like, “I was neither Black. I was neither

white. So I felt like stuck. I also wasn't Chinese enough. I had a family that—I

couldn't speak Chinese, so I just didn't feel like I belonged to that community

too.” That was the first time I could hear articulated what that identity is to

be in this in-between space and this fluctuation, which is like, Oh!

There's a tension that sort of released a little bit. I'm like, Oh, this is a

thing! (laughs) This is an actual identity. There's a community of people that

feel like this. It's not just like I'm just sort of a vector that just doesn't

belong into any particular space.

Then talking to, like, other Asian Americans in DC, too—Sojin Kim, who is like an amazing public historian here. She's like, “I am Korean American, but I do identify as Asian American.” I do think that has been a facet that I do feel community with other Asians who have immigrant parents who do exist in sort of this in-between space. It has been hard for me to just identify as Asian because I do feel like I've held a lot of tensions outward or, like, external self-identification of myself of belonging to a monolith that I don't belong to. So it's hard when I put down census information or demographic information, I don't put "Asian." I do the "other" and I put "Asian American" because I'm like, It's different!

And it has also because I actually have never been on the continent of Asia. I haven't ever been to Hong Kong or where my father grew up in southern China before. So it isn't accurate for me to really—I don't have that experience. I have a very specific cultural experience through the ways that I've moved through different places growing up in the States. So I feel very specific. Sometimes I do think, “Oh, I'm not really an Asian because I can't operate in certain facets or don't have some of those cultural connections sometimes.” But I grew up in a Chinese family, so it's funny that I still feel that way.

TSC: I love the way that you articulated the specificity of your experience, but also the way that it's connected to so many others' experiences of being Asian. I think that for me too, similarly, using the term Asian helps me feel connected to other people whose current way of being has been shaped by our racialization as Asian. So even if it's not necessarily an identifier that many of us fully understand or feel connected to, it has still shaped who we are today. And there's power in sharing that experience.

I want to talk a little bit about your work. What I find really exciting about you and your work is that you're always kind of integrating multiple fields and methodologies to work towards a goal that's often founded in equity, justice in the built environment. You're a landscape architect; you have an integrative design degree; you've worked in visual communications, in design research, participatory design. So I'm curious how you would describe your work and how your upbringing and your identity has shaped your creative path and also the way that you approach your work.

JL: They're all really good questions. I'm trying to think of which one—can you ask it one more time? I'm going to make sure I answer all three questions.

TSC: Sure! You don't have to answer them in order. It's just more like some questions for you to think about. Mostly I’m just curious how you would describe your work or what you do, and then how you feel that your upbringing or your identity has shaped your creative path and how you approach your work.

JL: Okay. Thank you. I would say that a large part of what motivates me is to bring visibility to things that are very much invisible. As a landscape architect, too, working in an architecture and engineering industry, I think, one, it was a profession that was sort of like a smaller profession within a bigger profession. And not having to be raised in that type of design space where we had to advocate and demonstrate value of things that are very much, like, viscerally, just part of people's experience. I think landscapes and sort of the broader context of place—we often take for granted that it even exists. So I was alwaysparticularly interested in, like, people should know and should see. And I don't think everyone sees the same way how those environments impact all parts of how you move through space, experience space, come together with community or not able to do any of those things.

So when it connects to, like, my equity and justice work, I think I had always thought that that was really a powerful thing that, like, landscape architecture and place had the power to do—to be able to really viscerally, tangibly shape and impact social and environmental change. That's just the places that we move within even though we're in our phones in digital spaces. It's just the foundation of our being. And then I was also just very mad that fundamentally was not part of what the strategy was in my thirteen years of professional practice. It was just completely absent for something that was very much, I thought, an obvious thing or something that I think maybe in very sort of small ways was probably mentioned when I first started school like in the early 2000s, but just you never hear of again, and still only kind of hear of today.

But because of that, it has evolved into a people thing. Whatever I had learned about the environment and ecology, I've taken analogous spaces into people and how people move together, work together, build community together. Emergent Strategyand adrienne maree brown's work started to really click. I was like, Oh, ecological systems and people systems all function the same way and we're all just living dynamic systems. So that was really exciting to me. I also just think that there's so much information that we don't know about the small things in life, about people's everyday existence, people's cultures, what really brings people together that just needs to be woven into how we shape our built environments.

So I think that's what is the biggest facet to me is that we have a very small group of individuals who shape what all of our lives are. Everybody is a planner or a designer in their own way, and everyone's doing the work and working really hard to figure out positive change in their own lives, in their own communities and family lives. So I feel like there's just so much to be acknowledged and built from—there is no divine inspiration; nothing is a new idea. There are so many people doing really incredible work that are doing “little d” design or “little p” planning that go really unrecognized.

But that to me was where innovation is and sustainability is. So it's just an obvious thing to me. And the things that really connect us all are about community. It's not the prettiest thing. So yeah, it evolved. It evolved from a very much like, I don't understand why we do this thing when it's very object-based. It's very much for a designer's particular gratification. But, at the end of the day, we're trying to build environments where everyone can experience and have joy in their everyday lives. So that's what the major driver is. And, now, it becomes really focused-to-me work trying to decenter anything that I've learned or trying to unlearn about what is inspiring and being translated into design decisions now. A little bit long-winded.

But I try to equate it to my equity and justice work in the sense that there's just so much about our built environment that we love deeply that is unrecognized and invisible. And making those things visible is, like, to me where the exciting stuff happens. I no longer get particularly excited about any sort of design thing. It's sort of pretty and cool. But then I get really excited when I see people building stuff with their communities, coming up with other things. So I love this profession in the sense that I'm in a constant state of learning. And the spaces I love learning in now is spaces that I'm not a part of. I'm learning from others and I'm getting schooled or unlearning things that I've had to construct over the past fifteen years in my professional career.

TSC: I'm also curious how you even knew about landscape architecture. How did you get into it? It's not like there's a lot of awareness around a whole lineage of immigrant Asian landscape architects in the US. (laughs)

JL: No. I didn't realize how trapped I was into this little community. It's pretty Waspy. My sister who's a very much more extroverted person than I am—when she was younger, she met some landscape architect on an airplane. It was very random. She just knows me very well, and she was like, “I really think that you would really be into this profession.” She knows that I have always been a creatively minded person, but I really had no—and I looked at architecture—but I still didn't really get architecture. (laughs) I was like, That's kind of cool, but I don't know if I can actually do that! So she had me meet this guy that she was on an airplane with because when she was living in Southern California—and it ended up being, I think, a guy that works at EDAW. Remember EDAW before AECOM?

TSC: Oh yes.

JL: The original. So, before AECOM emerged, it was EDAW, which was, I think, like, a very large corporate landscape architecture firm. It was in Irvine, California, where she was living in Orange County, and she's like, “Meet this guy.” I'm like, “Okay.” It was really fascinating to know that there was a profession that dealt with the spaces in between buildings. So it was so open—granted he was showing me golf courses, (laughs) and I'm sure I was looking at theme parks or something. But there was something about looking at these plan graphics, about shaping place and land that was like, “Whoa, this is fascinating to me!”

TSC: I love that—a profession that addresses the space in between buildings. I love the way that you describe everybody as being a designer or a planner in their own lives. I also resonate with getting most excited about seeing projects emerge from within communities that are about people getting together with each other and celebrating, or preserving, or strengthening, or working towards something with things that are already thereversus proposing new interventions or projects that can come from external influences. I almost wonder—regardless of whether you'd met that landscape architect or not and if you'd done something else, if you would still have landed where you are today.

Then talking to, like, other Asian Americans in DC, too—Sojin Kim, who is like an amazing public historian here. She's like, “I am Korean American, but I do identify as Asian American.” I do think that has been a facet that I do feel community with other Asians who have immigrant parents who do exist in sort of this in-between space. It has been hard for me to just identify as Asian because I do feel like I've held a lot of tensions outward or, like, external self-identification of myself of belonging to a monolith that I don't belong to. So it's hard when I put down census information or demographic information, I don't put "Asian." I do the "other" and I put "Asian American" because I'm like, It's different!

And it has also because I actually have never been on the continent of Asia. I haven't ever been to Hong Kong or where my father grew up in southern China before. So it isn't accurate for me to really—I don't have that experience. I have a very specific cultural experience through the ways that I've moved through different places growing up in the States. So I feel very specific. Sometimes I do think, “Oh, I'm not really an Asian because I can't operate in certain facets or don't have some of those cultural connections sometimes.” But I grew up in a Chinese family, so it's funny that I still feel that way.

TSC: I love the way that you articulated the specificity of your experience, but also the way that it's connected to so many others' experiences of being Asian. I think that for me too, similarly, using the term Asian helps me feel connected to other people whose current way of being has been shaped by our racialization as Asian. So even if it's not necessarily an identifier that many of us fully understand or feel connected to, it has still shaped who we are today. And there's power in sharing that experience.

I want to talk a little bit about your work. What I find really exciting about you and your work is that you're always kind of integrating multiple fields and methodologies to work towards a goal that's often founded in equity, justice in the built environment. You're a landscape architect; you have an integrative design degree; you've worked in visual communications, in design research, participatory design. So I'm curious how you would describe your work and how your upbringing and your identity has shaped your creative path and also the way that you approach your work.

JL: They're all really good questions. I'm trying to think of which one—can you ask it one more time? I'm going to make sure I answer all three questions.

TSC: Sure! You don't have to answer them in order. It's just more like some questions for you to think about. Mostly I’m just curious how you would describe your work or what you do, and then how you feel that your upbringing or your identity has shaped your creative path and how you approach your work.

JL: Okay. Thank you. I would say that a large part of what motivates me is to bring visibility to things that are very much invisible. As a landscape architect, too, working in an architecture and engineering industry, I think, one, it was a profession that was sort of like a smaller profession within a bigger profession. And not having to be raised in that type of design space where we had to advocate and demonstrate value of things that are very much, like, viscerally, just part of people's experience. I think landscapes and sort of the broader context of place—we often take for granted that it even exists. So I was alwaysparticularly interested in, like, people should know and should see. And I don't think everyone sees the same way how those environments impact all parts of how you move through space, experience space, come together with community or not able to do any of those things.

So when it connects to, like, my equity and justice work, I think I had always thought that that was really a powerful thing that, like, landscape architecture and place had the power to do—to be able to really viscerally, tangibly shape and impact social and environmental change. That's just the places that we move within even though we're in our phones in digital spaces. It's just the foundation of our being. And then I was also just very mad that fundamentally was not part of what the strategy was in my thirteen years of professional practice. It was just completely absent for something that was very much, I thought, an obvious thing or something that I think maybe in very sort of small ways was probably mentioned when I first started school like in the early 2000s, but just you never hear of again, and still only kind of hear of today.

But because of that, it has evolved into a people thing. Whatever I had learned about the environment and ecology, I've taken analogous spaces into people and how people move together, work together, build community together. Emergent Strategyand adrienne maree brown's work started to really click. I was like, Oh, ecological systems and people systems all function the same way and we're all just living dynamic systems. So that was really exciting to me. I also just think that there's so much information that we don't know about the small things in life, about people's everyday existence, people's cultures, what really brings people together that just needs to be woven into how we shape our built environments.

So I think that's what is the biggest facet to me is that we have a very small group of individuals who shape what all of our lives are. Everybody is a planner or a designer in their own way, and everyone's doing the work and working really hard to figure out positive change in their own lives, in their own communities and family lives. So I feel like there's just so much to be acknowledged and built from—there is no divine inspiration; nothing is a new idea. There are so many people doing really incredible work that are doing “little d” design or “little p” planning that go really unrecognized.

But that to me was where innovation is and sustainability is. So it's just an obvious thing to me. And the things that really connect us all are about community. It's not the prettiest thing. So yeah, it evolved. It evolved from a very much like, I don't understand why we do this thing when it's very object-based. It's very much for a designer's particular gratification. But, at the end of the day, we're trying to build environments where everyone can experience and have joy in their everyday lives. So that's what the major driver is. And, now, it becomes really focused-to-me work trying to decenter anything that I've learned or trying to unlearn about what is inspiring and being translated into design decisions now. A little bit long-winded.

But I try to equate it to my equity and justice work in the sense that there's just so much about our built environment that we love deeply that is unrecognized and invisible. And making those things visible is, like, to me where the exciting stuff happens. I no longer get particularly excited about any sort of design thing. It's sort of pretty and cool. But then I get really excited when I see people building stuff with their communities, coming up with other things. So I love this profession in the sense that I'm in a constant state of learning. And the spaces I love learning in now is spaces that I'm not a part of. I'm learning from others and I'm getting schooled or unlearning things that I've had to construct over the past fifteen years in my professional career.

TSC: I'm also curious how you even knew about landscape architecture. How did you get into it? It's not like there's a lot of awareness around a whole lineage of immigrant Asian landscape architects in the US. (laughs)

JL: No. I didn't realize how trapped I was into this little community. It's pretty Waspy. My sister who's a very much more extroverted person than I am—when she was younger, she met some landscape architect on an airplane. It was very random. She just knows me very well, and she was like, “I really think that you would really be into this profession.” She knows that I have always been a creatively minded person, but I really had no—and I looked at architecture—but I still didn't really get architecture. (laughs) I was like, That's kind of cool, but I don't know if I can actually do that! So she had me meet this guy that she was on an airplane with because when she was living in Southern California—and it ended up being, I think, a guy that works at EDAW. Remember EDAW before AECOM?

TSC: Oh yes.

JL: The original. So, before AECOM emerged, it was EDAW, which was, I think, like, a very large corporate landscape architecture firm. It was in Irvine, California, where she was living in Orange County, and she's like, “Meet this guy.” I'm like, “Okay.” It was really fascinating to know that there was a profession that dealt with the spaces in between buildings. So it was so open—granted he was showing me golf courses, (laughs) and I'm sure I was looking at theme parks or something. But there was something about looking at these plan graphics, about shaping place and land that was like, “Whoa, this is fascinating to me!”

TSC: I love that—a profession that addresses the space in between buildings. I love the way that you describe everybody as being a designer or a planner in their own lives. I also resonate with getting most excited about seeing projects emerge from within communities that are about people getting together with each other and celebrating, or preserving, or strengthening, or working towards something with things that are already thereversus proposing new interventions or projects that can come from external influences. I almost wonder—regardless of whether you'd met that landscape architect or not and if you'd done something else, if you would still have landed where you are today.

“That was the first time I could articulate what that identity is to be in this in-between space and this fluctuation, which is both like, Oh! There's a tension that sort of released a little bit.”

Interview Segment: A tension that released

JL: That's a really good

question. I think it would

always be something like—I do need to make things. I do think there's a part of me—most of the things I do now is,

like, community research—I do have an itch for it, and it could come from my

mother. It is this fact of like, What can you build with the things that you

have? She was always really great at that, just as a homemaker and a

seamstress. When you only have so much, you just figure out what do you got

with what you have, and you make something out of it. I find that such a cool

thing to do. She always had a huge bucket of scrap fabric where she would

construct things or like a pair of shorts or a shirt or something for a summer

even though, when I was a kid, I was like, “Eww, why would I wear this?” (laughs)

But she was always making things from things that other people didn't think of as things you would create with. She still always has a tiny little compost bucket that she just makes out of her cottage cheese containers. It's still on her sink. (laughs) Or things that people always buy or just don't think about. She upholsters her own couch for goodness’ sake! It's crazy.

So I think it stems from wanting to create things like that. She is a cook too, so I've actually even thought about—even before I went to grad school, I was like, Should I go to culinary school? It's funny because I'm not, like, an actual good cook, but I love the idea of constructing and composing something. So I'm fascinated by cooking not only from just a very comfort way, but I'm like, It does look like a very fascinating and intriguing design path—to create food! I'm like, Oh, that was always sort of an interesting facet.

TSC: Yeah! You're making me think about so many food-related things. I do think that there's a lot to be said about food, not just around creativity and design but also around what you were talking about before—the way that it brings people and communities together. If you run any community engagement event, you have to have food to either break the ice or bring people in—even just to get people to share a table with each other, sit together and share food. It can also be a point of entry or a low stakes way to share our cultures with each other.

JL: Yeah! It ended up being things I had to sort of trick some people into having conversation. I had to trick my mother to talk about family sometimes by just having her make something. I remember recording her making wontons and she'd just start. And I'd ask her questions because if I would sit her down for a formal interview or an oral history, she's like, “No, why would I tell you all these things?”

TSC: I love that! That's such a good idea. Having her make something and then just casually asking questions. That's also funny to me because I feel like that's the way that I ask questions to my parents too. It's always just casually inserting them in something else that's happening. But it's not the main focus because that would be too traumatic. (laughs)

JL: Exactly! Because they won't do it! I've tried it before. Even the 1882 Foundation doing oral histories or having any conversations with elders was really hard because they're like, “Why are you asking? I don't have anything to say. My story's not interesting.” Then you just put the little recorder to the side, and you have a round table and then you just start talking. If you bring their friends over it's like, “Okay, that’s how we’re going to do it.”

TSC: I love that. I'm going to piggyback on that in a second, but the other thing that you just made me think of was one of my favorite “dishes” to make is “stuff in the fridge.” I just open the fridge, see what's in here, and make something from what's in the fridge. My partner's like, “How did you make this out of nothing that's in the refrigerator?” I'm just like, “I don't know. There are things in there when you throw it together.” I'm much more that way than like, Here's this recipe that I'm going to go buy all the ingredients for and perfectly measure out. So you just made me think about that with your mom and being resourceful and looking around you and making something out of “nothing”—or what others may see as nothing, but where you recognize that there's value, especially when you bring it together with your own creativity.

But speaking of the 1882 Foundation—I think this is tied to your work with the Dear Chinatown DC mapping project, right?

JL: Yeah!

TSC: I wanted to talk about that a little bit because I was really inspired by that project. I'm curious how that idea came about or how you initiated the project and the partnerships, and then also what the experience was like for you doing community design work with and for other Chinese people about Chinese identity and experiences.

JL: I learned a lot. So the origins of that project, Dear Chinatown DC, emerged from my late graduate school experience. So I ended up going back to grad school at University of Michigan after being a landscape architect and doing traditional practice and working in a couple of nonprofits for about thirteen years. So what I really appreciated about the program—it was an integrated design program and the intention is to work with a community partner. To a degree, you're supposed to sort of go that avenue through what the university curated for you. But I had worked my entire sort of thirteen years doing what other people told me to do, working on projects other people have told me to. Something really interesting though—because a lot of academic advisors will tell you not to do a project that means something to you because you have a weird bias. For example, there was a couple of professors I remember specifically who were—to undergraduates, “Don't work on a project that you have a really deep connection to it because you get blinders of judgment to think critically about it,” which is, I think, so weird! (laughs)

TSC: I remember that era!

JL: Is that a thing? But I was like, “No, I'm going to do this. I need to work on a project about Chinatown.” And I had a deep curiosity for DC's Chinatown, which was a place that I just moved to in 2016. It was like a deeply invisible place. If you can just look at any sort of Google search of all of these assumptions people make and very judgements about a place they don't know about—is really profound. People are saying it's shrinking. It's not a real Chinatown. It looks like Disneyland. It's like, “What's this here? There's no Chinese people here, so this can't be an actual neighborhood.” So I wanted that to be the place I learned about more deeply and just did a lot of research to find my way to the 1882 Foundation, and it was very just kind of serendipitous.

But Ted Gong—it's funny. So you have a lot of these Asian Americans that grew up in the Civil Rights Movement era on the West Coast that have this particular identity. They have that identity, but they all were, like, federal employees that live in Northern Virginia and Maryland and DC. So they're all very sweet, but they all retired and this became their life—the 1882 Foundation. So Ted was actually really interested in a place-based project because their headquarters is stuffed in this little basement underneath a family association—the Moy Family Association. He saw sort of that changing neighborhood too. He draws—he's a very creative guy, but he has worked in the federal government. He worked at Homeland Security and Immigration all his life.

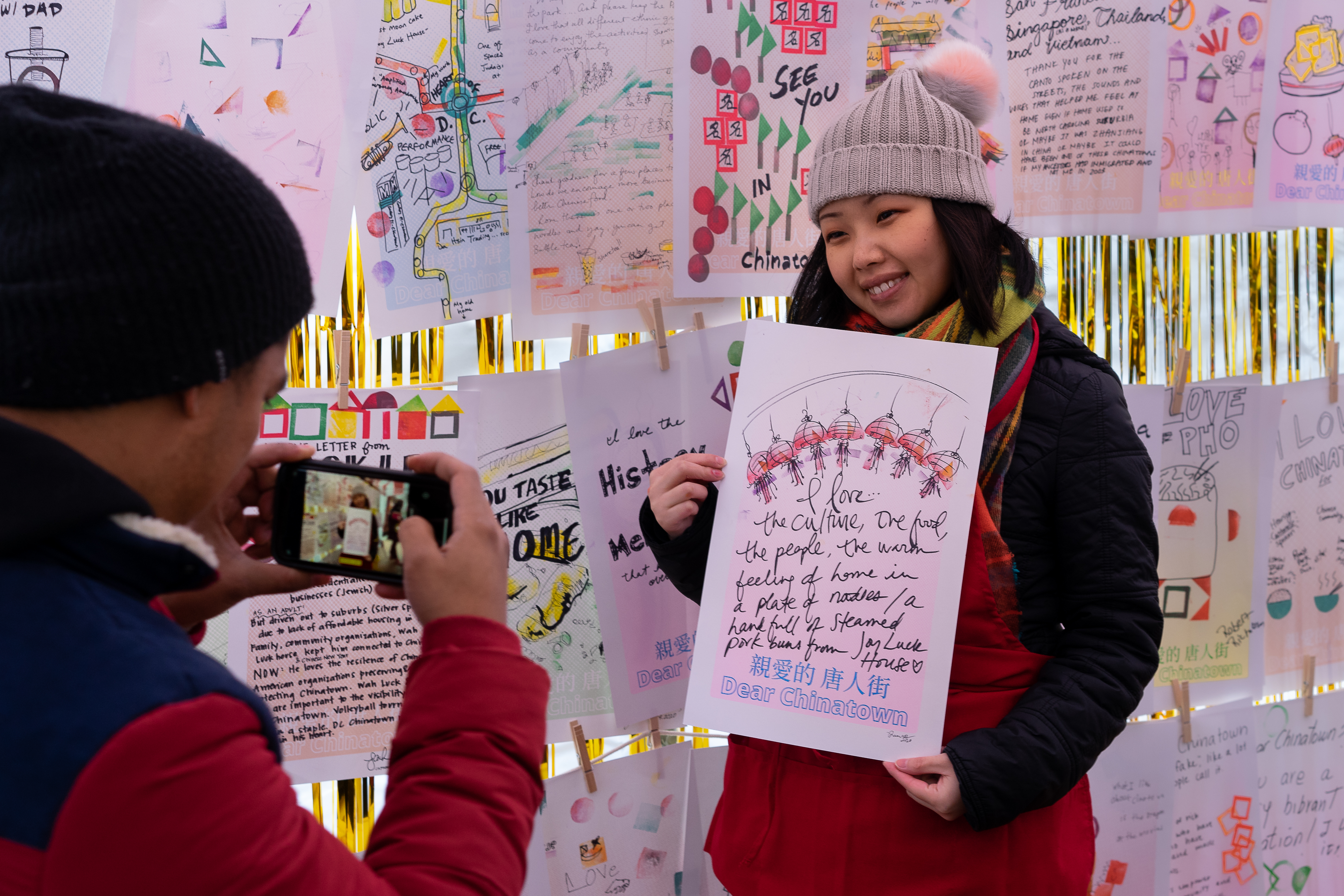

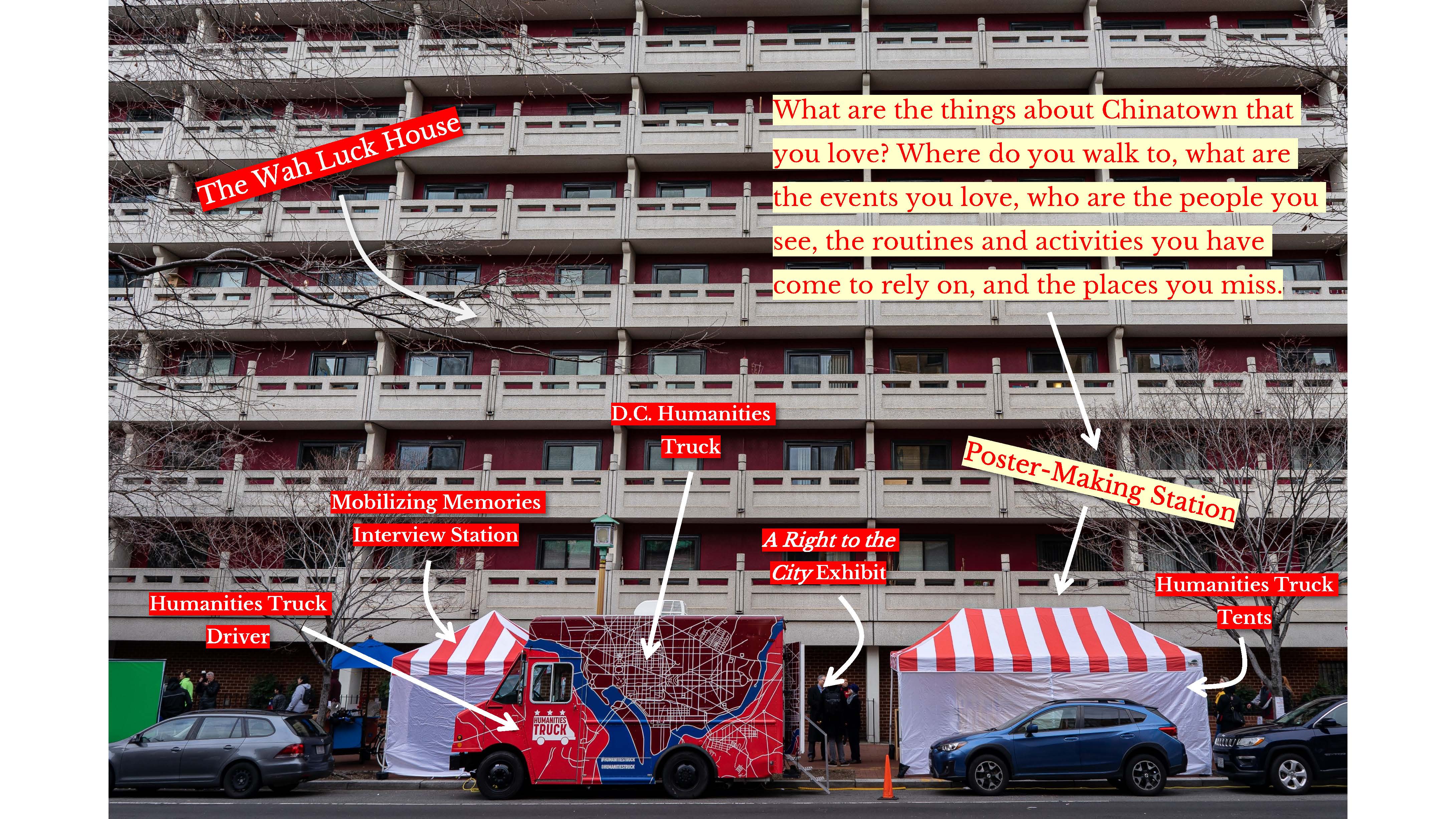

So he had a deep interest in this subject matter. And so that's how we sort of became partners and he became my community advisor and we just shared space together. I would just kind of follow along, go get lunch with Ted. I would go to what they have was called Talk Stories, which are these open mic nights that they had pre-pandemic, and they all just kind of went to the local church or they went to a basement of, like, a corporate building to do storytelling. So, through that partnership, I actually wanted to interrogate public engagement processes. So I did, like, a design research, an embodied prototype of doing something that was helpful to them because they were doing event stuff. So we were collaborating on a Chinese New Year parade and brought out a lot of people and created a whole sort of exhibit and poster-making, love-letter activity. There's this whole curated exhibit that exists for Chinatown through the Anacostia Community Museum. So we just brought all of those things together and placed it all in front of the Wah Luck House in DC's Chinatown, which is one of the few remaining public housing buildings in the neighborhood.

So it was just like a manifestation of the things that they do internally in their spaces and just try to bring it outside. Then there I just did a lot of observation and analysis and synthesis to have a conversation about what it actually means to have conversations, engage or learn from what is particularly meaningful and special about place to people, and found that also communities were very sort of fluid. We had people who lived in this particular Chinatown that are fewer, but there's also just a lot of connectedness to communities of people who live outside of the DC, because the DC boundaries are so kind of fuzzy because it's like a DC-Maryland-Virginia region. It's sort of all kind of a different bubble and it shows up differently than New York or San Francisco.

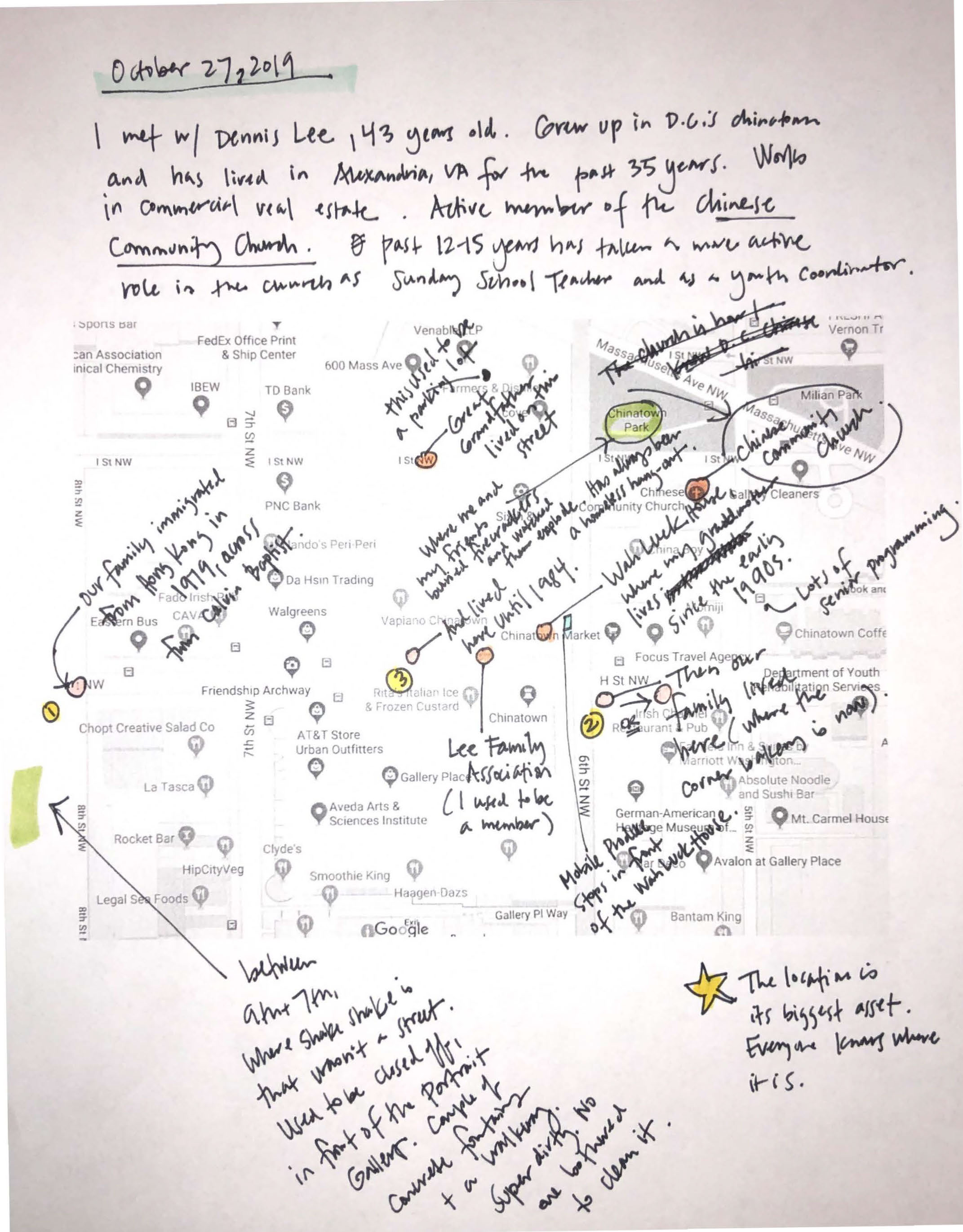

So that was, like, one facet and was able to just kind of map all of that together. That was just like a collection of that and just conversations and interviews. Each time I had an interview with different folks who were connected to DC's Chinatown or had a history and relationship to it, I'd make a little map-based interview of all the places that they had talked about in our interviews together and then translated all of that onto this map. It has been a long time; I haven't come back to it. It was supposed to be like a beta version, and, how projects go, I was anticipating a whole phase two and being able to make it interactive and people to be able to add data points too. A local teen actually got a hold of it, and she wanted to add things to the map for her capstone project this spring. She worked with my web developer and then added a bunch of business information to all the assets that are still there and exists for people to go to.

TSC: That's awesome!

JL: Long-term thing. One facet, longer term.

TSC: So it started out as a thesis project for your degree. Was that the kind of seed for it?

JL: Yeah. The seed for it was like a design research project really trying to interrogate public engagement processes. But, through that, most people from just looking at it as, like, a participatory art project. It was really inspired by—I wasn't the only one sort of doing that. A lot of different spaces were doing similar love-letter projects. So mine was like a very small one in the larger constellation of things happening. But I was also really inspired by—I was doing a lot of reading on what was happening in New York and the W.O.W. project. I was also reading a lot of Rosten Woo's past work too from Los Angeles. It was a lot of participatory work. So yeah, it's like letting everyday objects, everyday spaces breathe and have some visibility within a lot more noise in this particular neighborhood of people trying to shape a historic identity just through some calligraphy signage of, like, Fuddruckers or something. (laughs)

TSC: It's funny because I do think a lot of projects start off with people being like, “This is just the first phase and there'll other phases,” and then they kind of just sit there. But people find them! That’s exciting that that high school student found your project, wanted to add to it, and was inspired by it! I’ll just share that I have also been inspired by it. I heard you talk about it, I think, for the Carleton lecture series. I also cited it in an application that I put in recently.

JL: Aww. Thank you!

TSC: It was a question that was like, “What projects are you inspired by?” And yours was one of them I listed. So I think in that sense, it really is a seed for many people. Even if you never touch it again, I think that it’s already had a ripple effect where it's part of something greater. People see it and they get excited; they get inspired—and they want to do similar projects in their area. Maybe the phase two is everybody else that does projects from seeing and being inspired by that project of yours.

JL: Yeah. That's good to hear!

TSC: But also, maybe there is a real phase two! I'm not discouraging that.

JL: Maybe! (laughs)

TSC: Maybe, or maybe not! (laugh)

But she was always making things from things that other people didn't think of as things you would create with. She still always has a tiny little compost bucket that she just makes out of her cottage cheese containers. It's still on her sink. (laughs) Or things that people always buy or just don't think about. She upholsters her own couch for goodness’ sake! It's crazy.

So I think it stems from wanting to create things like that. She is a cook too, so I've actually even thought about—even before I went to grad school, I was like, Should I go to culinary school? It's funny because I'm not, like, an actual good cook, but I love the idea of constructing and composing something. So I'm fascinated by cooking not only from just a very comfort way, but I'm like, It does look like a very fascinating and intriguing design path—to create food! I'm like, Oh, that was always sort of an interesting facet.

TSC: Yeah! You're making me think about so many food-related things. I do think that there's a lot to be said about food, not just around creativity and design but also around what you were talking about before—the way that it brings people and communities together. If you run any community engagement event, you have to have food to either break the ice or bring people in—even just to get people to share a table with each other, sit together and share food. It can also be a point of entry or a low stakes way to share our cultures with each other.

JL: Yeah! It ended up being things I had to sort of trick some people into having conversation. I had to trick my mother to talk about family sometimes by just having her make something. I remember recording her making wontons and she'd just start. And I'd ask her questions because if I would sit her down for a formal interview or an oral history, she's like, “No, why would I tell you all these things?”

TSC: I love that! That's such a good idea. Having her make something and then just casually asking questions. That's also funny to me because I feel like that's the way that I ask questions to my parents too. It's always just casually inserting them in something else that's happening. But it's not the main focus because that would be too traumatic. (laughs)

JL: Exactly! Because they won't do it! I've tried it before. Even the 1882 Foundation doing oral histories or having any conversations with elders was really hard because they're like, “Why are you asking? I don't have anything to say. My story's not interesting.” Then you just put the little recorder to the side, and you have a round table and then you just start talking. If you bring their friends over it's like, “Okay, that’s how we’re going to do it.”

TSC: I love that. I'm going to piggyback on that in a second, but the other thing that you just made me think of was one of my favorite “dishes” to make is “stuff in the fridge.” I just open the fridge, see what's in here, and make something from what's in the fridge. My partner's like, “How did you make this out of nothing that's in the refrigerator?” I'm just like, “I don't know. There are things in there when you throw it together.” I'm much more that way than like, Here's this recipe that I'm going to go buy all the ingredients for and perfectly measure out. So you just made me think about that with your mom and being resourceful and looking around you and making something out of “nothing”—or what others may see as nothing, but where you recognize that there's value, especially when you bring it together with your own creativity.

But speaking of the 1882 Foundation—I think this is tied to your work with the Dear Chinatown DC mapping project, right?

JL: Yeah!

TSC: I wanted to talk about that a little bit because I was really inspired by that project. I'm curious how that idea came about or how you initiated the project and the partnerships, and then also what the experience was like for you doing community design work with and for other Chinese people about Chinese identity and experiences.

JL: I learned a lot. So the origins of that project, Dear Chinatown DC, emerged from my late graduate school experience. So I ended up going back to grad school at University of Michigan after being a landscape architect and doing traditional practice and working in a couple of nonprofits for about thirteen years. So what I really appreciated about the program—it was an integrated design program and the intention is to work with a community partner. To a degree, you're supposed to sort of go that avenue through what the university curated for you. But I had worked my entire sort of thirteen years doing what other people told me to do, working on projects other people have told me to. Something really interesting though—because a lot of academic advisors will tell you not to do a project that means something to you because you have a weird bias. For example, there was a couple of professors I remember specifically who were—to undergraduates, “Don't work on a project that you have a really deep connection to it because you get blinders of judgment to think critically about it,” which is, I think, so weird! (laughs)

TSC: I remember that era!

JL: Is that a thing? But I was like, “No, I'm going to do this. I need to work on a project about Chinatown.” And I had a deep curiosity for DC's Chinatown, which was a place that I just moved to in 2016. It was like a deeply invisible place. If you can just look at any sort of Google search of all of these assumptions people make and very judgements about a place they don't know about—is really profound. People are saying it's shrinking. It's not a real Chinatown. It looks like Disneyland. It's like, “What's this here? There's no Chinese people here, so this can't be an actual neighborhood.” So I wanted that to be the place I learned about more deeply and just did a lot of research to find my way to the 1882 Foundation, and it was very just kind of serendipitous.

But Ted Gong—it's funny. So you have a lot of these Asian Americans that grew up in the Civil Rights Movement era on the West Coast that have this particular identity. They have that identity, but they all were, like, federal employees that live in Northern Virginia and Maryland and DC. So they're all very sweet, but they all retired and this became their life—the 1882 Foundation. So Ted was actually really interested in a place-based project because their headquarters is stuffed in this little basement underneath a family association—the Moy Family Association. He saw sort of that changing neighborhood too. He draws—he's a very creative guy, but he has worked in the federal government. He worked at Homeland Security and Immigration all his life.

So he had a deep interest in this subject matter. And so that's how we sort of became partners and he became my community advisor and we just shared space together. I would just kind of follow along, go get lunch with Ted. I would go to what they have was called Talk Stories, which are these open mic nights that they had pre-pandemic, and they all just kind of went to the local church or they went to a basement of, like, a corporate building to do storytelling. So, through that partnership, I actually wanted to interrogate public engagement processes. So I did, like, a design research, an embodied prototype of doing something that was helpful to them because they were doing event stuff. So we were collaborating on a Chinese New Year parade and brought out a lot of people and created a whole sort of exhibit and poster-making, love-letter activity. There's this whole curated exhibit that exists for Chinatown through the Anacostia Community Museum. So we just brought all of those things together and placed it all in front of the Wah Luck House in DC's Chinatown, which is one of the few remaining public housing buildings in the neighborhood.

So it was just like a manifestation of the things that they do internally in their spaces and just try to bring it outside. Then there I just did a lot of observation and analysis and synthesis to have a conversation about what it actually means to have conversations, engage or learn from what is particularly meaningful and special about place to people, and found that also communities were very sort of fluid. We had people who lived in this particular Chinatown that are fewer, but there's also just a lot of connectedness to communities of people who live outside of the DC, because the DC boundaries are so kind of fuzzy because it's like a DC-Maryland-Virginia region. It's sort of all kind of a different bubble and it shows up differently than New York or San Francisco.

So that was, like, one facet and was able to just kind of map all of that together. That was just like a collection of that and just conversations and interviews. Each time I had an interview with different folks who were connected to DC's Chinatown or had a history and relationship to it, I'd make a little map-based interview of all the places that they had talked about in our interviews together and then translated all of that onto this map. It has been a long time; I haven't come back to it. It was supposed to be like a beta version, and, how projects go, I was anticipating a whole phase two and being able to make it interactive and people to be able to add data points too. A local teen actually got a hold of it, and she wanted to add things to the map for her capstone project this spring. She worked with my web developer and then added a bunch of business information to all the assets that are still there and exists for people to go to.

TSC: That's awesome!

JL: Long-term thing. One facet, longer term.

TSC: So it started out as a thesis project for your degree. Was that the kind of seed for it?

JL: Yeah. The seed for it was like a design research project really trying to interrogate public engagement processes. But, through that, most people from just looking at it as, like, a participatory art project. It was really inspired by—I wasn't the only one sort of doing that. A lot of different spaces were doing similar love-letter projects. So mine was like a very small one in the larger constellation of things happening. But I was also really inspired by—I was doing a lot of reading on what was happening in New York and the W.O.W. project. I was also reading a lot of Rosten Woo's past work too from Los Angeles. It was a lot of participatory work. So yeah, it's like letting everyday objects, everyday spaces breathe and have some visibility within a lot more noise in this particular neighborhood of people trying to shape a historic identity just through some calligraphy signage of, like, Fuddruckers or something. (laughs)

TSC: It's funny because I do think a lot of projects start off with people being like, “This is just the first phase and there'll other phases,” and then they kind of just sit there. But people find them! That’s exciting that that high school student found your project, wanted to add to it, and was inspired by it! I’ll just share that I have also been inspired by it. I heard you talk about it, I think, for the Carleton lecture series. I also cited it in an application that I put in recently.

JL: Aww. Thank you!

TSC: It was a question that was like, “What projects are you inspired by?” And yours was one of them I listed. So I think in that sense, it really is a seed for many people. Even if you never touch it again, I think that it’s already had a ripple effect where it's part of something greater. People see it and they get excited; they get inspired—and they want to do similar projects in their area. Maybe the phase two is everybody else that does projects from seeing and being inspired by that project of yours.

JL: Yeah. That's good to hear!

TSC: But also, maybe there is a real phase two! I'm not discouraging that.

JL: Maybe! (laughs)

TSC: Maybe, or maybe not! (laugh)

“When I was a kid, I was like, ‘Eww, why would I wear this?’ But she was always making things from things that other people didn't think of as things you would create with. She still always has a tiny little compost bucket that she just makes out of her cottage cheese containers. It's still on her sink.”

JL: No, but that's a

really good point too! Because I'm like, Well, what's the catalyst for letting this to sort of

breathe on its own? I appreciated that it manifests into something that was

really beyond my control or me trying to make a particular widget. It’s garnered,

I think, what was helpful—like Ted would have a lot of conversations with city

council, and he continues to be more visible when people didn't even know he

was there in the neighborhood. So I think he's in more active

conversations. I think we were able to channel all of that energy—I was able to channel that energy

to build a studio for University of Washington virtually during the pandemic.

So we did some work there where actually Ted and Justin met. That's how Ted got

money from the Mellon Foundation to be able to build out the storytelling

center in their own space that they've been dreaming about for the past twelve

years too. So I was like, Oh, outcomes come out differently sometimes. As a designer, you don't anticipate being like, Oh, I don't have to

build a thingy. What can the thingy that I contribute to then sort of like—

TSC: Emergent strategy-like.

JL: Yeah, exactly!—just go off on its own.

TSC: I think it's good to keep in mind too that when your project comes to a close, even if the outcome is not what you thought it would be, that maybe the project hasn't ended yet. Maybe the project is still going, or certain threads will come back to you, or you'll come back around to people or moments later down the line in ways that you don't even know about, so that's exciting.

JL: It's a neat thing! It's also just so foreign to me because I feel like so much of my existence was like, “Oh, I just need to make the thing or produce the thing.”

TSC: Yes! What are the deliverables? (laughs)

JL: (laughs) I don't know if that was like a self-inflicted identity of not being the person that can contribute to something that can move other people forward.

TSC: I'm curious what challenges you feel like you've faced as a Chinese American designer and educator. And then also if you've ever felt like it has benefited or privileged you in any way?

TSC: Emergent strategy-like.

JL: Yeah, exactly!—just go off on its own.

TSC: I think it's good to keep in mind too that when your project comes to a close, even if the outcome is not what you thought it would be, that maybe the project hasn't ended yet. Maybe the project is still going, or certain threads will come back to you, or you'll come back around to people or moments later down the line in ways that you don't even know about, so that's exciting.

JL: It's a neat thing! It's also just so foreign to me because I feel like so much of my existence was like, “Oh, I just need to make the thing or produce the thing.”

TSC: Yes! What are the deliverables? (laughs)

JL: (laughs) I don't know if that was like a self-inflicted identity of not being the person that can contribute to something that can move other people forward.

TSC: I'm curious what challenges you feel like you've faced as a Chinese American designer and educator. And then also if you've ever felt like it has benefited or privileged you in any way?

“Well, what's the catalyst for letting this to sort of breathe on its own? I appreciated that it manifests into something that was really beyond my control or me trying to make a particular widget.”

JL: Benefit and privilege,

I think the model minority

thing is a hard thing to shake off. It torments my brain a lot because we work

in a profession that—and then also to drive positive change, you got to hustle (laughs)

and you got to move. It's hard for me because I am a very impatient person and

I want things to change; I want things to get done. I worry a lot about what I

am expressing outwardly when I embody those things too, especially as an East

Asian woman too. I don't want to exist in a world that has built me to be a

person that my value was about production and about getting things perfect and

right. It's hard, but then the world is crumbling and you're like, Well, what

other course do I have besides just sitting there and doing nothing about

things? (laughs)

But it has been a privilege. I know how to get stuff done. And I think being and having had a particular sort of history and experience has privileged me to being one that has a reputation of being someone that can get things done and get things done reliably. I'm an easy person to work with—I think for the most part. But I think there's a lot of things that—sometimes I'm like, “Oh, do I get taken advantage of? Do I get sort of pushed where I don't need to be pushed?” And also, it racks my brain sometimes when I'm not super, super explicit about my intentions—of what people think my intentions are sometimes—because not every Asian American, Chinese American does justice work. Some could care less about it—people have their own things and values and what we want to do.

But maybe because I'm also an internal person and I'm not extroverted, I feel like I'm like, “Oh, I'm always tired of having to explain the work that I do, or that I'm capable of doing this work”—not to mean that I don't have biases, and I continue to kind of reflect on the work I do and how I am also even relating to younger folks too, getting older and being a manager and having to steward teams. That's a whole other challenge in itself now that I'm back into a studio and doing full-time work. And being like, “Yeah, we got pushed,” but then I'm like, “Oh, am I being that person that used to push me that just created a lot of anxiety around myself and my work?”

So, yeah, I think there's a lot of privilege in being a Chinese American, East Asian woman in this space. I have a lot of self-internal conflict that I think I will unpack and continue to process for the rest of my life around that identity too. What was the other question? You had another really good question that was another component of that.

TSC: I think you answered it in a way. I mean, I asked what challenges you feel like you face and also how you feel like you've benefited or felt privileged by your identity. It sounded to me like you were explaining the model minority as both a privilege and a challenge because on one hand, when people expect things of you, you tend to be more capable—when you grow up with people expecting you to be able to do things, it is a privilege in a way, right? But also, there is the challenge of your worth being tied to your productivity and also of you having to constantly explain your positionality or your justice-oriented approach to the work because people may not assume that about you given the model minority myth stereotyping Asians as hard-working and conforming. Maybe you had more to say about either of those, but that's kind of what I heard from your answer.

JL: Yeah, that's actually really accurate. Thanks for reflecting that back. And then also maybe it's just being a designer and also wanting to do a lot of things. I just get overwhelmed by all the things I want to be doing. A lot of my interest in understanding myself specifically was understanding Black American spaces and histories too, first as an avenue, and then for me to unpack my own history. And I feel a lot of guilt for also not making the space to first understand my own histories before I looked at other BIPOC spaces and histories, especially when it comes to professions or space and the built environment. So there's this balance, too, of that as well.

TSC: You feel guilt exploring your own identity experience over centering Black and Brown communities, or what do you mean? Can you say that one more time?

But it has been a privilege. I know how to get stuff done. And I think being and having had a particular sort of history and experience has privileged me to being one that has a reputation of being someone that can get things done and get things done reliably. I'm an easy person to work with—I think for the most part. But I think there's a lot of things that—sometimes I'm like, “Oh, do I get taken advantage of? Do I get sort of pushed where I don't need to be pushed?” And also, it racks my brain sometimes when I'm not super, super explicit about my intentions—of what people think my intentions are sometimes—because not every Asian American, Chinese American does justice work. Some could care less about it—people have their own things and values and what we want to do.

But maybe because I'm also an internal person and I'm not extroverted, I feel like I'm like, “Oh, I'm always tired of having to explain the work that I do, or that I'm capable of doing this work”—not to mean that I don't have biases, and I continue to kind of reflect on the work I do and how I am also even relating to younger folks too, getting older and being a manager and having to steward teams. That's a whole other challenge in itself now that I'm back into a studio and doing full-time work. And being like, “Yeah, we got pushed,” but then I'm like, “Oh, am I being that person that used to push me that just created a lot of anxiety around myself and my work?”

So, yeah, I think there's a lot of privilege in being a Chinese American, East Asian woman in this space. I have a lot of self-internal conflict that I think I will unpack and continue to process for the rest of my life around that identity too. What was the other question? You had another really good question that was another component of that.

TSC: I think you answered it in a way. I mean, I asked what challenges you feel like you face and also how you feel like you've benefited or felt privileged by your identity. It sounded to me like you were explaining the model minority as both a privilege and a challenge because on one hand, when people expect things of you, you tend to be more capable—when you grow up with people expecting you to be able to do things, it is a privilege in a way, right? But also, there is the challenge of your worth being tied to your productivity and also of you having to constantly explain your positionality or your justice-oriented approach to the work because people may not assume that about you given the model minority myth stereotyping Asians as hard-working and conforming. Maybe you had more to say about either of those, but that's kind of what I heard from your answer.

JL: Yeah, that's actually really accurate. Thanks for reflecting that back. And then also maybe it's just being a designer and also wanting to do a lot of things. I just get overwhelmed by all the things I want to be doing. A lot of my interest in understanding myself specifically was understanding Black American spaces and histories too, first as an avenue, and then for me to unpack my own history. And I feel a lot of guilt for also not making the space to first understand my own histories before I looked at other BIPOC spaces and histories, especially when it comes to professions or space and the built environment. So there's this balance, too, of that as well.

TSC: You feel guilt exploring your own identity experience over centering Black and Brown communities, or what do you mean? Can you say that one more time?

“I don't want to exist in a

world that has built me to be a person that my value was about production and

about getting things perfect and right. It's hard, but then the world is

crumbling and you're like, Well, what other course do I have besides just

sitting there and doing nothing about things?”

JL: I think both ways. I think because

often, I have a lot of guilt because I don't feel like it

was until adulthood that I've gotten to start to unpack my Asian American and

Chinese American identity and history. But it was also really important for me

specifically to understand BIPOC spaces and experiences, specifically the Black

experience in America first. And then for me it had that entry. But then I feel

guilty. I'm like, Why didn’t I ever take an Asian American ethnic studies

class? It still rocks my brain. What seems to be an obvious avenue—and I

hadn't, especially within some of the spaces that I take up too. So it's like,

How do I exist with other BIPOC communities when I haven’t even necessarily

completely delved into the depths of my own histories?

TSC: Ok I understand. That is so relatable and I feel similar. It’s the Cathy Park Hong quote about "Asians being next in line to be white,” right? Where we just kind of blend in and then we see ourselves as people who don't need to look at our own experience, our own identity with that critical lens or even think about our racialization. So we've been privileged to not have to alwaysthink about our racialization in some cases. The older I get, though, the more I realize that's not true. But, at least when I was younger, I definitely felt like that was true.