“Cooking food is community engagement. Feeding people is community engagement. And it’s about identity. It’s about nourishment. It’s about generosity. It’s color. It’s all the things I am.”

she/her

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I'm here with Shalini Agrawal for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in Asian Diaspora.

To get started, I would love it if you would tell me about the places where you grew up. In what ways did they feel connected to, or disconnected from, your homeland or your ancestral home?

Shalini Agrawal (SA): I was born in Canada, but I moved back and forth between Canada and India. So the question here is how I connected with my ancestral land?

TSC: Or—just tell me about your experience growing up and where you grew up. It sounds like you were moving back and forth so you had a bit of a transnational upbringing. What was that experience like?

SA: What really stands out for me growing up in Canada was this sense of difference. My parents were literally the only immigrants of any kind. They had come seeking out a better life. My father came from privilege, and his father was a self-made man—my grandfather—and really hard working, really smart—and was an accomplished and revered engineer. My father was an engineer, too, and I think he was a little bit in his shadow, and he wanted to venture out on his own.

So he had made this decision to move to Canada. I remember feeling not different, but then, being treated differently. My name became this—this huge point of difference for me.

I just became very aware of being really different and wanting to be like everyone else. I look back now, and, seeing my parents now, I think it was really traumatic. Just thinking about trauma and engaging with communities who experience displacement and othering—I think that they were in their own survival of trying to make it and survive. And all they knew was their culture, and my home was very, very Indian. We ate the food; I only spoke Hindi when I was young. But I spent a lot of time trying to erase who I was, wanting to blend in as much as possible. I would try to disappear. I was very quiet and very shy and didn't want to make my presence known.

I have a distinct memory when I was young of actually being seen. There was a teacher that did notice me and actually pulled me forward in a way in which it's like, “I believe that you can do things that everyone else can.” That was a transformative experience for me. I was in third grade, and, if I had my hand up, she would pick me. For the lead for the class play, she picked me. And I remember that was such a transformative moment because I was around all these blonde girls—it was Hansel and Gretel, I still remember. I remember thinking, I'm never going to get picked, and here's the one Brown girl in the class, and she picked me! And all those girls were like, What? She gets to be Gretel? (laughs)

TSC: So you got picked to be Gretel? That’s incredible! (laughs)

SA: And I was so excited!

TSC: Do you know who that teacher is? That's such a great story.

SA: I do remember—Mrs. Lawn. Sadly, she ended up dying of breast cancer. I kept in touch with her after I moved from Canada to the US.

I would say that's the second part—moving to the United States and feeling much more of an acute sense of difference than when I was in Canada. When I came to the US, there was such a strong sense of not belonging and of being an outsider.

TSC: I have so many follow-up questions. Where did you end up in the US when you moved back here?

SA: My father was transferring jobs, and we ended up in a suburb of Chicago, and it was the southwest of Chicago—was very white, very Christian. I was there for four years, and then I moved to New Jersey, which was much more diverse. And that's where my parents still live. I went to college, and I kept moving. But New Jersey and the East Coast now are definitely more home base.

TSC: Do you ever wonder if your parents want to move back to India?

SA: You know, that’s a very interesting conversation. My parents have said they regret coming.

TSC: Really?

SA: That's really hard for me to hear. I feel on many levels that it was hard for them. I work so hard to also make a space and life for myself like, “I’ve been working so hard to make it work, and you’re regretting that we're here?” That says a lot. Yeah.

TSC: Wow. That is a lot. That's really heavy.

I’m curious if there are spaces, either now or in your past, where you saw yourself, or your community, or your own stories reflected? Did you have that experience growing up? Or do you have that experience now, especially now that you're not living in Chicago anymore?

SA: There's a lot of people who immigrated—were born in India and left. Me and my partner, we're one of the few whose parents left, and we were born outside of the country. And so there's very few of us in our age group. When I met my partner, we connected implicitly on our shared lived experiences; he understood all the angst and all the things that are hard for me!

I didn't see myself reflected in spaces around me until I moved out to New Jersey, where there was like one or two other Indians. We moved to a good school district, and there were a lot more Asians. I was like, Oh, I’m meeting people who share the same values as me! I have often said that was really transformative; it really helped me to emerge into my own. Because until that point in my life, I was the only one. I had one friend who was Korean in fifth grade. That was it. Everyone else was white.

TSC: That's so different from my experience of growing up in the Bay Area. It's so interesting to hear about yours.

I'm curious whether you identify as Asian or Asian American? Do you think that that word feels empowering to you? Does it feel limiting to you, especially growing up so isolated?

SA: It’s so interesting because, when I was young, they didn't have a box for my racial identity. When I used to take the standardized tests in school, I would literally check the box “other” for a really long time.

TSC: So they didn't have “Asian” as a checkbox?

SA: They didn’t have “Asian.”

TSC: Wow. Oh my goodness.

SA: I think it was “White,” “Black,” maybe “Spanish,” and “other.”

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I'm here with Shalini Agrawal for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in Asian Diaspora.

To get started, I would love it if you would tell me about the places where you grew up. In what ways did they feel connected to, or disconnected from, your homeland or your ancestral home?

Shalini Agrawal (SA): I was born in Canada, but I moved back and forth between Canada and India. So the question here is how I connected with my ancestral land?

TSC: Or—just tell me about your experience growing up and where you grew up. It sounds like you were moving back and forth so you had a bit of a transnational upbringing. What was that experience like?

SA: What really stands out for me growing up in Canada was this sense of difference. My parents were literally the only immigrants of any kind. They had come seeking out a better life. My father came from privilege, and his father was a self-made man—my grandfather—and really hard working, really smart—and was an accomplished and revered engineer. My father was an engineer, too, and I think he was a little bit in his shadow, and he wanted to venture out on his own.

So he had made this decision to move to Canada. I remember feeling not different, but then, being treated differently. My name became this—this huge point of difference for me.

I just became very aware of being really different and wanting to be like everyone else. I look back now, and, seeing my parents now, I think it was really traumatic. Just thinking about trauma and engaging with communities who experience displacement and othering—I think that they were in their own survival of trying to make it and survive. And all they knew was their culture, and my home was very, very Indian. We ate the food; I only spoke Hindi when I was young. But I spent a lot of time trying to erase who I was, wanting to blend in as much as possible. I would try to disappear. I was very quiet and very shy and didn't want to make my presence known.

I have a distinct memory when I was young of actually being seen. There was a teacher that did notice me and actually pulled me forward in a way in which it's like, “I believe that you can do things that everyone else can.” That was a transformative experience for me. I was in third grade, and, if I had my hand up, she would pick me. For the lead for the class play, she picked me. And I remember that was such a transformative moment because I was around all these blonde girls—it was Hansel and Gretel, I still remember. I remember thinking, I'm never going to get picked, and here's the one Brown girl in the class, and she picked me! And all those girls were like, What? She gets to be Gretel? (laughs)

TSC: So you got picked to be Gretel? That’s incredible! (laughs)

SA: And I was so excited!

TSC: Do you know who that teacher is? That's such a great story.

SA: I do remember—Mrs. Lawn. Sadly, she ended up dying of breast cancer. I kept in touch with her after I moved from Canada to the US.

I would say that's the second part—moving to the United States and feeling much more of an acute sense of difference than when I was in Canada. When I came to the US, there was such a strong sense of not belonging and of being an outsider.

TSC: I have so many follow-up questions. Where did you end up in the US when you moved back here?

SA: My father was transferring jobs, and we ended up in a suburb of Chicago, and it was the southwest of Chicago—was very white, very Christian. I was there for four years, and then I moved to New Jersey, which was much more diverse. And that's where my parents still live. I went to college, and I kept moving. But New Jersey and the East Coast now are definitely more home base.

TSC: Do you ever wonder if your parents want to move back to India?

SA: You know, that’s a very interesting conversation. My parents have said they regret coming.

TSC: Really?

SA: That's really hard for me to hear. I feel on many levels that it was hard for them. I work so hard to also make a space and life for myself like, “I’ve been working so hard to make it work, and you’re regretting that we're here?” That says a lot. Yeah.

TSC: Wow. That is a lot. That's really heavy.

I’m curious if there are spaces, either now or in your past, where you saw yourself, or your community, or your own stories reflected? Did you have that experience growing up? Or do you have that experience now, especially now that you're not living in Chicago anymore?

SA: There's a lot of people who immigrated—were born in India and left. Me and my partner, we're one of the few whose parents left, and we were born outside of the country. And so there's very few of us in our age group. When I met my partner, we connected implicitly on our shared lived experiences; he understood all the angst and all the things that are hard for me!

I didn't see myself reflected in spaces around me until I moved out to New Jersey, where there was like one or two other Indians. We moved to a good school district, and there were a lot more Asians. I was like, Oh, I’m meeting people who share the same values as me! I have often said that was really transformative; it really helped me to emerge into my own. Because until that point in my life, I was the only one. I had one friend who was Korean in fifth grade. That was it. Everyone else was white.

TSC: That's so different from my experience of growing up in the Bay Area. It's so interesting to hear about yours.

I'm curious whether you identify as Asian or Asian American? Do you think that that word feels empowering to you? Does it feel limiting to you, especially growing up so isolated?

SA: It’s so interesting because, when I was young, they didn't have a box for my racial identity. When I used to take the standardized tests in school, I would literally check the box “other” for a really long time.

TSC: So they didn't have “Asian” as a checkbox?

SA: They didn’t have “Asian.”

TSC: Wow. Oh my goodness.

SA: I think it was “White,” “Black,” maybe “Spanish,” and “other.”

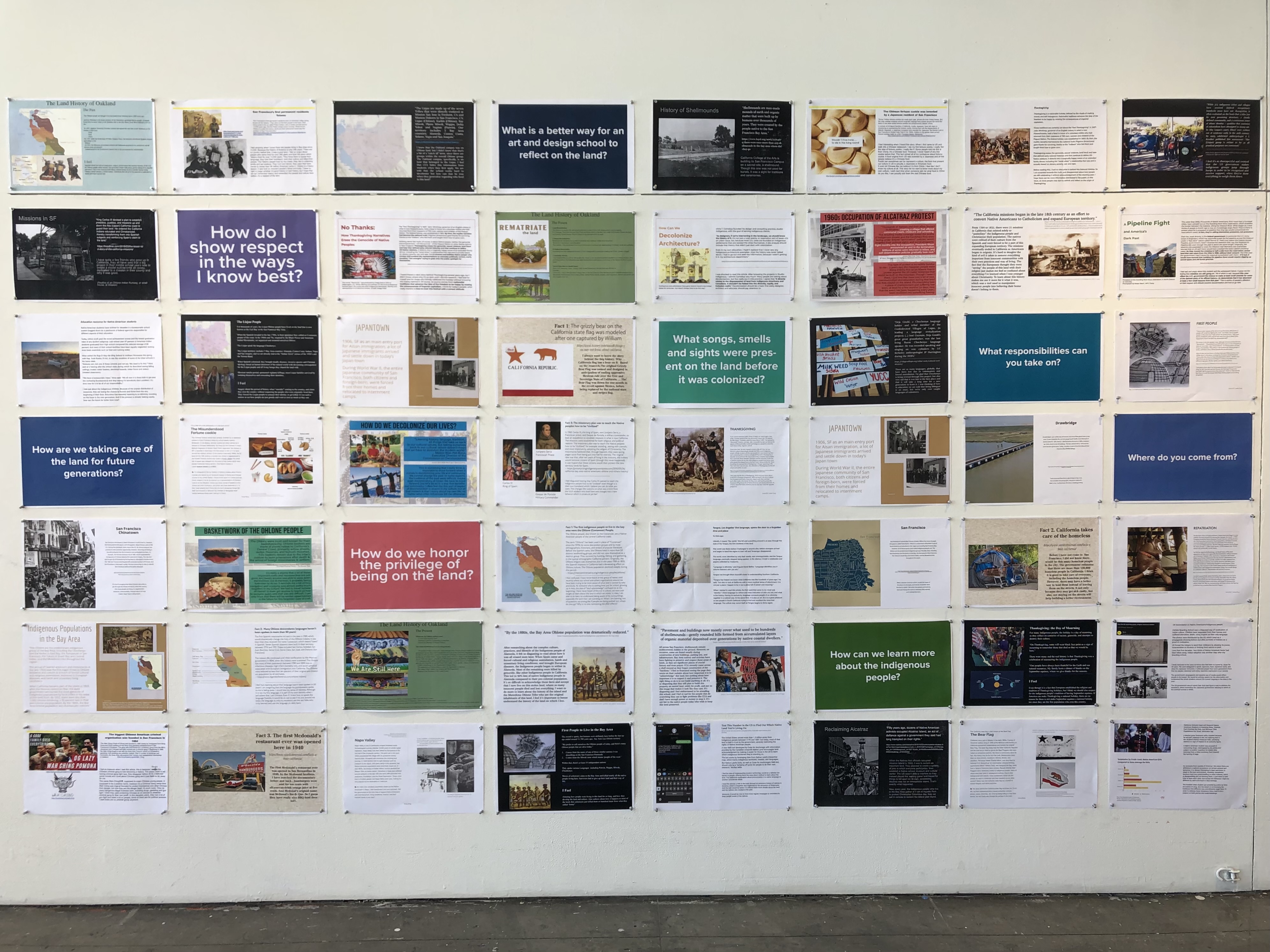

Interview Segment: How are you a guest?

INTERVIEW 01 DETAILS

Narrator:

Shalini Agrawal, she/her

Interview Date:

January 23, 2023

Keywords:

Themes: South Asian identity, community engagement, participatory design, decolonial design, food, internalized racism, assimilation, colonialism, mispronouncing names, women of color, cultural holidays, immigrant narratives, ancestral knowledge, healing

Places: India, New Delhi, Chandigarh, Chicago, Canada

References: Grace Lee Boggs, Le Corbusier, Nek Chand

ABOUT SHALINI

Ancestral Land:

North India

Homeland:

Tiohtiá:ke (Montreal, Canada)

Current Land:

Ohlone (East Bay, Lafayette, CA)

Diaspora Story:

I was born in Montreal but moved between Canada and India during my childhood mainly to be with family. My father was drawn towards the dream of more opportunity, but never felt a sense of community. I have never felt like I belong to either place.

Creative Fields:

Interdisciplinary, architecture, community

engagement

Racial Justice Affiliations:

Pathways to Equity, Dark Matter U, Decolonial School

Favorite Fruit:

Mango, passionfruit, guava, sumo oranges

Biography:

Shalini Agrawal is an interdisciplinarian with training in architecture and is the founder of Public Design for Equity. She is the director for Pathways to Equity, a leadership program of Open Architecture Collaborative that trains architects and designers in racial justice workshops. She works with interdisciplinary practitioners, firms, and organizations to address equity in the workplace and community engagement. She teaches at California College of the Arts, facilitating curriculum aimed at decolonizing design and architecture practices.

︎ publicdesignforequity.org

I identify as South Asian, when people ask me, because I do think that word “Asian” erases so much. There’s so much difference in so many ways between me and you with respect to being “Asian.” And I’m like, we're the most populous countries in the world, and it’s like one lump, you know, one group of people, and I think—like I would say that when I say “Asian,” it defaults to Chinese and Korean and Japanese, but I don't think it defaults as much to Indian, perhaps, and that’s my understanding. So I will often say I'm “South Asian.”

TSC: Yeah, I agree.

How would you describe your work? And how has your upbringing and your identity shaped your creative path and the way that you approach your work?

SA: Yeah, great question. There is a direct line. And you may have heard me tell this story, but I’ll tell it again for the purpose of this. I was talking earlier about my grandfather, and he was a civil engineer.

Well, before I talk about my grandfather, I’ll tell you about an experience that I had. I've always been searching for something else in architecture. I was taught architecture, and I loved the design aspect, but I just felt like I wanted to do something more, and I sent myself on a research fellowship. It was really just a trip to India. My cousins are architects there as well, so I was like, This is a great reason for me to go.

So I went to India, and I just observed, basically, as one does with research, and that was the first time I had seen and experienced the community involved in the design. I remember sitting in a village, and we were talking about doing an artist colony and each artisan—each group of artisans—would have their own area to make. It was basically makerspaces—make and living spaces. And so we were working with the dyers, and these were people who were dying saris. And saris, if you know, are very, very long pieces of fabric. There are 6 yards—18 feet—and you need a big, long area to hang these fabrics. And these craftspeople were saying we need straight lines to be able to dry these fabrics.

They sat there and drew exactly what they needed in the dirt with their fingers. And so they were drawing a plan of how much space they needed in order to hang these fabrics, and that was my first time seeing that and thinking, Oh my gosh! We have to have people involved in the design of their spaces! Because, if it was a Western or European architect, they would have done like a European-styled courtyard or village. It was that summer that introduced me to participatory design.

I went up to Chandigarh to see Le Corbusier's building and I was so underwhelmed. It was a four-hour trip, and, because I was a student in architecture and I was learning about these buildings and my teacher literally wrote the book on Le Corbusier, I’m going to go see the building. It is, like, very classically his style. And there's nobody there. This is a country of a billion people, and it's completely devoid of energy and people. And we had driven four hours. I had to force myself to stay there for like ten minutes.

TSC: Oh wow—because it was that underwhelming?

SA: It was like a desert! It was literally like you're taking the vibrancy and erasing it and putting this monument.

Across the street was a person [Nek Chand] that worked in that building, and he was a self-taught artist. And so my cousin was like, “You should go see this also.” And it was like fourteen acres of outdoor gardens, outdoor rooms. And so here's this person who worked at the building, and my story was, he was so oppressed with where he was working that he had to make these outdoor spaces because they're completely opposite. They're made out of recycled materials. They're soft. They're smooth. They’re art. They're beautiful. They're different. They're thematic. They're completely, completely different from Le Corbusier, the antithesis. And that was also like, Who do I want to be? Who do I want to play with? I do not want to play with these modernists. I want to play with these people doing stuff that's so much more fun. So there were really these moments that transformed me. That was the first experience where I felt like, Oh, here is the answer: participatory design.

TSC: Yeah, I agree.

How would you describe your work? And how has your upbringing and your identity shaped your creative path and the way that you approach your work?

SA: Yeah, great question. There is a direct line. And you may have heard me tell this story, but I’ll tell it again for the purpose of this. I was talking earlier about my grandfather, and he was a civil engineer.

Well, before I talk about my grandfather, I’ll tell you about an experience that I had. I've always been searching for something else in architecture. I was taught architecture, and I loved the design aspect, but I just felt like I wanted to do something more, and I sent myself on a research fellowship. It was really just a trip to India. My cousins are architects there as well, so I was like, This is a great reason for me to go.

So I went to India, and I just observed, basically, as one does with research, and that was the first time I had seen and experienced the community involved in the design. I remember sitting in a village, and we were talking about doing an artist colony and each artisan—each group of artisans—would have their own area to make. It was basically makerspaces—make and living spaces. And so we were working with the dyers, and these were people who were dying saris. And saris, if you know, are very, very long pieces of fabric. There are 6 yards—18 feet—and you need a big, long area to hang these fabrics. And these craftspeople were saying we need straight lines to be able to dry these fabrics.

They sat there and drew exactly what they needed in the dirt with their fingers. And so they were drawing a plan of how much space they needed in order to hang these fabrics, and that was my first time seeing that and thinking, Oh my gosh! We have to have people involved in the design of their spaces! Because, if it was a Western or European architect, they would have done like a European-styled courtyard or village. It was that summer that introduced me to participatory design.

I went up to Chandigarh to see Le Corbusier's building and I was so underwhelmed. It was a four-hour trip, and, because I was a student in architecture and I was learning about these buildings and my teacher literally wrote the book on Le Corbusier, I’m going to go see the building. It is, like, very classically his style. And there's nobody there. This is a country of a billion people, and it's completely devoid of energy and people. And we had driven four hours. I had to force myself to stay there for like ten minutes.

TSC: Oh wow—because it was that underwhelming?

SA: It was like a desert! It was literally like you're taking the vibrancy and erasing it and putting this monument.

Across the street was a person [Nek Chand] that worked in that building, and he was a self-taught artist. And so my cousin was like, “You should go see this also.” And it was like fourteen acres of outdoor gardens, outdoor rooms. And so here's this person who worked at the building, and my story was, he was so oppressed with where he was working that he had to make these outdoor spaces because they're completely opposite. They're made out of recycled materials. They're soft. They're smooth. They’re art. They're beautiful. They're different. They're thematic. They're completely, completely different from Le Corbusier, the antithesis. And that was also like, Who do I want to be? Who do I want to play with? I do not want to play with these modernists. I want to play with these people doing stuff that's so much more fun. So there were really these moments that transformed me. That was the first experience where I felt like, Oh, here is the answer: participatory design.

“I identify as South Asian, when people ask me, because I do think that word “Asian” erases so much. There’s so much difference in so many ways between me and you with respect to being “Asian.”

And in another trip—I can't remember which trip this was—and I’d say this is where my most recent interest has been—and it’s actually remembering this memory—it didn't happen in the moment. But my uncle was driving me around New Delhi—and New Delhi, the capital of the country, is designed by legends—and I remember him saying, “Look at how much good the English has done for India. They built all these systems; they put this infrastructure. Look at how much good they've done.” And that's when I was like, Even when the oppressors have left, they still take up space, and it is represented through architecture. So that is why I’m really interested in decolonial practices. Because I see how architecture is quite literally a weapon of colonization, and it remains even when the physical people aren't there. It takes up space in people's minds and psyches and spheres—for generations. This gets passed down even a generation later. So yeah, long story, but I love how it's tied to my background! Like, I’ve told these stories individually, but now that I’m telling you, I’m like, Oh! It's so amazing that this has come through.

And then, the last thing is talking about my grandfather. He's a civil engineer, and he worked for the colonizers. He worked for the British government during that time, and my other grandfather was a follower of Gandhi, and his family was thrown in jail. So I really like to say I’m the intersection of the built environment and social justice; I’m supposed to be doing what I’m doing.

TSC: Wow! That's amazing. That's so powerful.

SA: It's like these facts that you live with your whole life, and I think a lot of times growing up as Indian and Asian, South Asian, I'm so busy trying to fit in that sometimes these things that I have lived with my whole life don’t make connections. And I made these connections doing a community engagement project and talking about identity.

TSC: Really? And were you running the project, or participating in the project?

SA: I was preparing a meal, and it was in the making of the meal that I made this connection. I just remember, They did the work for me to be doing what I’m doing today!

TSC: That's incredible.

SA: It's really powerful.

TSC: I'm thinking about that experience you had with the craftspeople in India dying saris and how they drew exactly what they needed in the dirt with their fingers. That wasn't just about participatory design; it was also about the relevance of your own identity in design—and that you could actually use your skills and knowledge to address something specific to your own culture, which is an incredible revelation. I know you've done a lot of work with participatory design and decolonial design and scholarship, and I'm curious if any of your work has more directly addressed South Asian identity, history, or themes, and if so, what that experience was like.

SA: Yeah, you mean, like working with the South Asian community? You know what? It hasn’t directly. I think there's a lot of influence that I take from it, but because I guess there's been so few of us for some time that I did not really have a lot of South Asian communities, and also, like, the work that my community and my people traditionally do is not this, right? The immigrant story is like engineer or doctor. Even architect is a little bit of an outlier! So yeah, I mean it to this day—I think my parents don't quite understand what I do.

TSC: Totally. I can relate.

And then, the last thing is talking about my grandfather. He's a civil engineer, and he worked for the colonizers. He worked for the British government during that time, and my other grandfather was a follower of Gandhi, and his family was thrown in jail. So I really like to say I’m the intersection of the built environment and social justice; I’m supposed to be doing what I’m doing.

TSC: Wow! That's amazing. That's so powerful.

SA: It's like these facts that you live with your whole life, and I think a lot of times growing up as Indian and Asian, South Asian, I'm so busy trying to fit in that sometimes these things that I have lived with my whole life don’t make connections. And I made these connections doing a community engagement project and talking about identity.

TSC: Really? And were you running the project, or participating in the project?

SA: I was preparing a meal, and it was in the making of the meal that I made this connection. I just remember, They did the work for me to be doing what I’m doing today!

TSC: That's incredible.

SA: It's really powerful.

TSC: I'm thinking about that experience you had with the craftspeople in India dying saris and how they drew exactly what they needed in the dirt with their fingers. That wasn't just about participatory design; it was also about the relevance of your own identity in design—and that you could actually use your skills and knowledge to address something specific to your own culture, which is an incredible revelation. I know you've done a lot of work with participatory design and decolonial design and scholarship, and I'm curious if any of your work has more directly addressed South Asian identity, history, or themes, and if so, what that experience was like.

SA: Yeah, you mean, like working with the South Asian community? You know what? It hasn’t directly. I think there's a lot of influence that I take from it, but because I guess there's been so few of us for some time that I did not really have a lot of South Asian communities, and also, like, the work that my community and my people traditionally do is not this, right? The immigrant story is like engineer or doctor. Even architect is a little bit of an outlier! So yeah, I mean it to this day—I think my parents don't quite understand what I do.

TSC: Totally. I can relate.

“Even when the oppressors have left, they still take up space, and it is represented through architecture. So that is why I’m really interested in decolonial practices. Because I see how architecture is quite literally a weapon of colonization, and it remains even when the physical people aren't there.”

SA: I've always felt like a fringe practitioner, and so I know very few Indian architects in general. Now there's many more, but I mean there were so few. I think what has happened is who I am has come through a lot in my work. I used to try to not be me, and I’d say that I'm just much more comfortable talking about that, and I have seen connecting with other women, especially women who are from here, or who are maybe immigrants and who live here. They're just so grateful because I think there's so much of this practice of erasing who you are or who I am, or who we are. And so I think a lot of times people are really happy hearing this is what it looks like to be unapologetically who you are and this is how it can be in practice. I have wanted to do projects, but I haven't worked in India. I also wanted to work in my own backyard. I'm from here. I really chose to work in my communities that are here, rather than seek other communities.

TSC: Yes. I love that. And it seems to me that your experience of growing up feeling othered and erasing your own identity really comes through in the way you see and make others feel seen in your process and your methods. I think it allows you to humanize both the work and the people that you work with. That’s really powerful.

SA: I know you and I have talked about the food thing, but that became a vehicle for connection on so many levels. So, when we talk about community engagement, everyone's talking about the toolkits and the skills. And yes, those are all important. But I actually ask, How are you a guest? For me, it's about food. Cooking food is community engagement. Feeding people is community engagement. And it’s about identity. It's about nourishment. It's about generosity. It's color. It's all the things I am. It’s a representation of my whole background, and it's how I can share in a way that allows people to enter in the way they want to receive. I’m not trying to teach anyone about my background. What I am trying to do is just share it. I'm seeing that surrounding myself with the flavors and the smells and the feelings—and that was when I made this connection with my family.

TSC: That's amazing. I'm getting goosebumps as I’m hearing you talk about it!

SA: And you know also seeing it as feminine labor. I come from a lineage of smart, strong women and having to balance gender dynamics and all of this. My grandmother was incredibly headstrong and smart, but also played the traditional role of mother and wife. I also want to acknowledge the feminine in all of this, even though I’m talking about my grandfathers.

TSC: I know you’ve talked about this a little bit, but I wanted to ask you what challenges you’ve faced as a South Asian designer and how has that influenced how you operate or how you feel about your own identity?

SA: Before I step into a room, people are making assumptions about who I am. When I meet someone for the first time, I’m going to have to go through a different type of introduction—about how do you say my name? Where are you from? Where are you really from? It’s the same conversation that has played out my whole life.

I think I forgot who I was for a long time. It’s so interesting because the name is such a symbolic way of me talking about my story—about how I grew up—and everyone mispronounced my name, and I let them mispronounce my name all the way through high school. And then, when I got to college, people aren’t going to see my name written. I can just say it and people will have to listen. They won’t have to rely on their eyes and reading. They will have to listen. And, of course, then people pronounced my name right, and that just was so empowering—like, it's such a simple thing. And I never wanted to change it. People would ask, Do you want to change your name? My parents even asked me.

TSC: Yes. I love that. And it seems to me that your experience of growing up feeling othered and erasing your own identity really comes through in the way you see and make others feel seen in your process and your methods. I think it allows you to humanize both the work and the people that you work with. That’s really powerful.

SA: I know you and I have talked about the food thing, but that became a vehicle for connection on so many levels. So, when we talk about community engagement, everyone's talking about the toolkits and the skills. And yes, those are all important. But I actually ask, How are you a guest? For me, it's about food. Cooking food is community engagement. Feeding people is community engagement. And it’s about identity. It's about nourishment. It's about generosity. It's color. It's all the things I am. It’s a representation of my whole background, and it's how I can share in a way that allows people to enter in the way they want to receive. I’m not trying to teach anyone about my background. What I am trying to do is just share it. I'm seeing that surrounding myself with the flavors and the smells and the feelings—and that was when I made this connection with my family.

TSC: That's amazing. I'm getting goosebumps as I’m hearing you talk about it!

SA: And you know also seeing it as feminine labor. I come from a lineage of smart, strong women and having to balance gender dynamics and all of this. My grandmother was incredibly headstrong and smart, but also played the traditional role of mother and wife. I also want to acknowledge the feminine in all of this, even though I’m talking about my grandfathers.

TSC: I know you’ve talked about this a little bit, but I wanted to ask you what challenges you’ve faced as a South Asian designer and how has that influenced how you operate or how you feel about your own identity?

SA: Before I step into a room, people are making assumptions about who I am. When I meet someone for the first time, I’m going to have to go through a different type of introduction—about how do you say my name? Where are you from? Where are you really from? It’s the same conversation that has played out my whole life.

I think I forgot who I was for a long time. It’s so interesting because the name is such a symbolic way of me talking about my story—about how I grew up—and everyone mispronounced my name, and I let them mispronounce my name all the way through high school. And then, when I got to college, people aren’t going to see my name written. I can just say it and people will have to listen. They won’t have to rely on their eyes and reading. They will have to listen. And, of course, then people pronounced my name right, and that just was so empowering—like, it's such a simple thing. And I never wanted to change it. People would ask, Do you want to change your name? My parents even asked me.

“They're just so grateful because I think there's so much of this practice of erasing who you are or who I am, or who we are. And so I think a lot of times people are really happy hearing this is what it looks like to be unapologetically who you are and this is how it can be in practice. ”

I just find that that is such an interesting way of kind of reflecting on how difference is received in this country. When something is hard, there’s a sense of, number one, not trying, or erasing, and, number two, renaming: “I can't say this, so can I call you this?” And so quite literally colonizing difference. I think that has been a big challenge for me. I think part of it is I have been incredibly quiet and shy. I was uncomfortable correcting others to contend with my difference. That's why my daughters have easy-to-pronounce Indian names.

To me it’s a metaphor. There are so many other things like food and of course the skin—and, like, being misinformed. You know, people thought I was Native Canadian, which was also an interesting thing—like in Canada they spend more time teaching about Native Canadian history. People would say, You're Indian, and I'd say, “I’m from India.”

And I remember living with this history of violence and genocide and being like, I'm not that. This incredible fear that I would be a victim of the violence—because the history of Native Canadians was also incredibly violent. I’m not Native Canadian; this is my internal racism. I was taught about Christopher Columbus thinking that he’d landed in India, and I was like, He killed all these people! Those could have been Indians. Those were meant to be Indians.

TSC: And yeah, the naming of your daughters, I totally understand it. Just the other day I was saying, “It's so nice that Xenia’s Chinese name, Sēnyǎ, is nice in its anglicized form whereas my name in its anglicized form just sounds terrible.” You know, my Chinese name is Xīntián, and I don't even know how people would pronounce that. But yeah, I remember thinking it’s so nice that Sēnyǎ is a “pretty” name in English.

SA: Yeah, interesting! By the way, I love, love, loved the whole story of the name. I ate it all up. No, I did! Because—I think—because of this experience, right?

TSC: Yes! Thanks.

On the other side, have you ever felt that being Asian has benefited or privileged you in any way?

SA: My parents were part of that immigration wave where they let in highly skilled and educated immigrants. They were the select group, so yeah, I mean, the people that we knew and that I grew up with were all professionals. As we kind of met more and more Indians, basically, all of them were either engineers or doctors. So there was this sense of privilege from the beginning. I do remember it being hard. So it wasn't that you were a doctor or an engineer and you automatically were doing well. People were struggling, and people had small homes, and I mean, I think there's this privilege of education that's always been pervasive in my life. But Asians still are experiencing racism, but one of the things that bothers me so much is the wanting to be white. I remember believing that whiteness was better than Asian.

This desire to be white and replicate the white suburban middle-class lifestyle—people in my generation wanted to have the story of success and beat white people at their own game, but you had to work harder.

TSC: Are you saying that witnessing this desire to assimilate and to be white within your own South Asian community made you distance yourself from them?

SA: Yes. Not to say that I wasn't replicating whiteness. But it was wanting to assimilate to whiteness, and then you had the competition on top of that. So it's almost like there's the culture of scarcity, which is kind of also ingrained in everything. We have our place, but you only get this much. We're all fighting for these fewer places without really thinking about equity. You have to be twice as good and there's less space for you.

TSC: Right, yeah.

I want to learn a little bit more about the solidarity work that you do. And so I am curious what brought you to Dark Matter U and Design as Protest and how you got involved.

SA: I have sought out different ways of practicing in architecture. Well, I've always felt alone within architecture doing this work—I mean, I've been doing it for longer than my kids have been alive. I call it my third child, like starting a nonprofit.

TSC: Maybe it should be your first child.

SA: My third child! My first nonprofit, third child. But yeah, maybe it is my first child. (laughs) But, I mean, I took my daughter to the job sites—I was always marginalized in the profession, always positioned on the edges. And so, for me, Dark Matter U was a space where people aren’t going to put me in this set box and I'm going to be able to walk into this space without having to prove myself and also there's people who care.

It was really wanting a space of belonging; that was the thing that drew me. And yeah, I mean, I think the solidary work is so tied to the community work. And I am a collaborator; I can't do anything by myself. Part of this is that I acknowledged that my people, my culture, are racist. That is something that I know I grew up with. And I know I do have racist tendencies, and so part of this is me doing my work and recognizing that, oh, I was wrong—and I see so much of it prevalent in my community. I have thought about how I can actually be engaged in that. I don't know how.

I went to this great workshop where it was Middle Eastern, North African, and South Asian artists talking about racism in our culture, and that was fantastic because it kind of gave me the language and the skills and tools to have these conversations. It is something that I am not proud of. There’s no excuse, but I also know that I have been part of that. And so part of this is to make amends for myself, and it's the work that I feel responsible to do. And I think—gosh, there is that Asian woman—gosh! I'm forgetting her name. The one in San Francisco. She was an activist.

TSC: Grace Lee Boggs?

SA: That's it! I'm sorry. Part of this was being in solidarity with Black and Brown people, being in solidarity towards racial equity for all of us—like, I really believe that. And so, when I talk about equity, it's about, like, I have this privilege from the fact that my parents had a starting point that was privileged, and not everyone has that same starting point. And so part of this is seeing equity for people who need it the most, if you will. “Rising tides lift all boats.” I really, really believe that. Yeah.

TSC: You talked a lot about racism amongst your own people, within your own community. What do you think is the role specifically of South Asians and other Asian Americans in solidarity work? Or do you think there is a specific role?

SA: Gosh, I think they just need to stop making it about themselves. It's like this is the thing that really just makes me sad. It's like everyone thinks that there's a small piece of the pie that all of us are fighting for, and I wish that people would see that there's enough for everyone. We just have to kind of come together in order to claim it! It's white supremacy saying that there's less for you and you have to make do. It's just waking up to the knowledge that there's actually more than enough for everyone, and we need to do this together. We're stronger together. We're stronger in numbers as opposed to trying to say, This is yours. This is mine. Regardless of what you want or what you think someone else should get you, we should be doing this! We should be doing this all together.=

To me it’s a metaphor. There are so many other things like food and of course the skin—and, like, being misinformed. You know, people thought I was Native Canadian, which was also an interesting thing—like in Canada they spend more time teaching about Native Canadian history. People would say, You're Indian, and I'd say, “I’m from India.”

And I remember living with this history of violence and genocide and being like, I'm not that. This incredible fear that I would be a victim of the violence—because the history of Native Canadians was also incredibly violent. I’m not Native Canadian; this is my internal racism. I was taught about Christopher Columbus thinking that he’d landed in India, and I was like, He killed all these people! Those could have been Indians. Those were meant to be Indians.

TSC: And yeah, the naming of your daughters, I totally understand it. Just the other day I was saying, “It's so nice that Xenia’s Chinese name, Sēnyǎ, is nice in its anglicized form whereas my name in its anglicized form just sounds terrible.” You know, my Chinese name is Xīntián, and I don't even know how people would pronounce that. But yeah, I remember thinking it’s so nice that Sēnyǎ is a “pretty” name in English.

SA: Yeah, interesting! By the way, I love, love, loved the whole story of the name. I ate it all up. No, I did! Because—I think—because of this experience, right?

TSC: Yes! Thanks.

On the other side, have you ever felt that being Asian has benefited or privileged you in any way?

SA: My parents were part of that immigration wave where they let in highly skilled and educated immigrants. They were the select group, so yeah, I mean, the people that we knew and that I grew up with were all professionals. As we kind of met more and more Indians, basically, all of them were either engineers or doctors. So there was this sense of privilege from the beginning. I do remember it being hard. So it wasn't that you were a doctor or an engineer and you automatically were doing well. People were struggling, and people had small homes, and I mean, I think there's this privilege of education that's always been pervasive in my life. But Asians still are experiencing racism, but one of the things that bothers me so much is the wanting to be white. I remember believing that whiteness was better than Asian.

This desire to be white and replicate the white suburban middle-class lifestyle—people in my generation wanted to have the story of success and beat white people at their own game, but you had to work harder.

TSC: Are you saying that witnessing this desire to assimilate and to be white within your own South Asian community made you distance yourself from them?

SA: Yes. Not to say that I wasn't replicating whiteness. But it was wanting to assimilate to whiteness, and then you had the competition on top of that. So it's almost like there's the culture of scarcity, which is kind of also ingrained in everything. We have our place, but you only get this much. We're all fighting for these fewer places without really thinking about equity. You have to be twice as good and there's less space for you.

TSC: Right, yeah.

I want to learn a little bit more about the solidarity work that you do. And so I am curious what brought you to Dark Matter U and Design as Protest and how you got involved.

SA: I have sought out different ways of practicing in architecture. Well, I've always felt alone within architecture doing this work—I mean, I've been doing it for longer than my kids have been alive. I call it my third child, like starting a nonprofit.

TSC: Maybe it should be your first child.

SA: My third child! My first nonprofit, third child. But yeah, maybe it is my first child. (laughs) But, I mean, I took my daughter to the job sites—I was always marginalized in the profession, always positioned on the edges. And so, for me, Dark Matter U was a space where people aren’t going to put me in this set box and I'm going to be able to walk into this space without having to prove myself and also there's people who care.

It was really wanting a space of belonging; that was the thing that drew me. And yeah, I mean, I think the solidary work is so tied to the community work. And I am a collaborator; I can't do anything by myself. Part of this is that I acknowledged that my people, my culture, are racist. That is something that I know I grew up with. And I know I do have racist tendencies, and so part of this is me doing my work and recognizing that, oh, I was wrong—and I see so much of it prevalent in my community. I have thought about how I can actually be engaged in that. I don't know how.

I went to this great workshop where it was Middle Eastern, North African, and South Asian artists talking about racism in our culture, and that was fantastic because it kind of gave me the language and the skills and tools to have these conversations. It is something that I am not proud of. There’s no excuse, but I also know that I have been part of that. And so part of this is to make amends for myself, and it's the work that I feel responsible to do. And I think—gosh, there is that Asian woman—gosh! I'm forgetting her name. The one in San Francisco. She was an activist.

TSC: Grace Lee Boggs?

SA: That's it! I'm sorry. Part of this was being in solidarity with Black and Brown people, being in solidarity towards racial equity for all of us—like, I really believe that. And so, when I talk about equity, it's about, like, I have this privilege from the fact that my parents had a starting point that was privileged, and not everyone has that same starting point. And so part of this is seeing equity for people who need it the most, if you will. “Rising tides lift all boats.” I really, really believe that. Yeah.

TSC: You talked a lot about racism amongst your own people, within your own community. What do you think is the role specifically of South Asians and other Asian Americans in solidarity work? Or do you think there is a specific role?

SA: Gosh, I think they just need to stop making it about themselves. It's like this is the thing that really just makes me sad. It's like everyone thinks that there's a small piece of the pie that all of us are fighting for, and I wish that people would see that there's enough for everyone. We just have to kind of come together in order to claim it! It's white supremacy saying that there's less for you and you have to make do. It's just waking up to the knowledge that there's actually more than enough for everyone, and we need to do this together. We're stronger together. We're stronger in numbers as opposed to trying to say, This is yours. This is mine. Regardless of what you want or what you think someone else should get you, we should be doing this! We should be doing this all together.=

“I just find that that is such an interesting way of kind of reflecting on how difference is received in this country. When something is hard, there’s a sense of, number one, not trying, or erasing, and, number two, renaming: ‘I can't say this, so can I call you this?’ And so quite literally colonizing difference.”

I mean, the term “women of color” was created by Black women for that very reason. I think that the history of that term, or that identity, was created by Black women who realized that we're in this all together, and I would say that term is so empowering—like, I love being part of women of color. I love it! I think I’m always searching for places to belong.

TSC: Totally. Yeah, that's really powerful. I mean, I do think that I don't necessarily identify as a woman, but I do think I identify more as a woman of color. That feels more authentic to me. I’ve never really thought about that until you just told that history.

SA: Yeah! I think I heard that really interesting history about that—like, I can’t remember—it might have been in the seventies or something or sixties—where Black women were like, We're stronger together! Let's call everyone else! And so I love that. Of course, Black women are amazing. They're the ones who are the trailblazers with the solidarity work.

And there are amazing South Asians that do solidarity work. I know in India that they are tirelessly fighting against the institution—government institutions and corporations. I know there are amazing, amazing women. And so I think part of that is we aren't hearing those stories either, right? So part of that is that capitalism and white supremacy don’t want those stories to be revealed or to get the light of day. And I mean, I do know a lot of Indian women who do social justice work in India and also here as well. So I do think there's a group of us doing it. Yeah.

TSC: How would you describe your role in Dark Matter U? I want to talk about this a little bit more because I'm just curious how you feel in BIPOC spaces. There’s obviously racial dynamics that are still at play, and I’m always conscious of that saying that “you don't need white people to reproduce white supremacy.” I would just love to hear you talk a little more about your role. I know you run Office Hours and you're on the People team—

SA: I'm on the People slash Opportunity team. And I have kind of with Office Hours been a little bit delinquent, but I mean, for me, Dark Matter U, first of all, is a place for me to belong, and where I can kind of not have to explain myself, like, just be welcomed. But I see my role as supporting everyone and anyone there. I didn't have this support. And how can I be in solidarity with Black—especially Black, as well as, I would say, Indigenous (I don't know if we have Indigenous people) and Latino, Latine, Latinx, or Latina. So, I mean, to me, it’s to be an ally and to do the work. So I’m just constantly like, There's so much work that hasn't been done on behalf of supporting diversity in BIPOC. And so that's what I see my role is like—volunteering, doing what I can, supporting, stepping in when I can. Yeah, a hundred percent. Yeah, wherever I’m needed. A model of allyship for me is literally stepping in whenever I can, leveraging what knowledge, resources, privilege, anything—

TSC: And do you feel supported in the space?

SA: I do! I mean, I feel like I’m older. So I’m in a different place in my life. But I do feel like—I mean, like with you! Asking you, “Can you help me? Can you share your application?” Like, that was so, like—I don't have this sense of, “I'm an elder,” or whatever, even though I think I am an elder! Just by my age! (laughs)

TSC: (laughs) You’re not an elder. I mean, by how much I respect you, you’re an elder, but by age, you’re not an elder.

SA: (laughs) But that’s the thing! I love that I can learn with and from other people. I mean, that's the other thing, to be in solidarity, to learn with and from people, and to experience what it is to be in a space where, yeah—I would have never guessed that this is what it could be like for me. But yeah, I'm not sure myself what my role is, but I do think that I’m trying to support and fill in where needed. Yeah. And to leverage whatever power and privilege I can for the benefit of others.

TSC: Yeah. That’s beautiful.

SA: Yeah! Well, I wish someone—well, I have had people do this for me.

TSC: That teacher!

SA: Yeah, that teacher and other people who, like, saw me and saw the potential for me to do the work that I was trying to do, even though I didn't really even believe it myself. I've seen it happen with my daughter. My daughter has this great mentor, and she is just propelled—it’s like the power of mentorship is like—

TSC: It’s so real.

SA: It’s so real!

TSC: So real. Yeah, just feeling seen and even just somebody acknowledging you and validating you.

SA: Totally, yeah. Gretel! Being Gretel!

TSC: Yes! Gretel! That is so incredible and so funny, because I remember doing theater when I was very young. I was very outgoing, and really loud, and I just had a really big personality. I wouldn't say that I don't now, but I think I switch it up based on who I’m around. Because, you know, there were many years of teachers saying I was bossy, or writing my name on the board, all these things.

But I do remember getting cast in a lead role in middle school. And it was like a frog. I don't remember what the play was about, but I was the lead, and it was a frog, and I was super excited. But then, as I got older, the teachers stopped casting me as lead roles, and I think it’s because—at least I felt like it was because I was Asian.

SA: Yeah.

TSC: So I just think it's funny that you have an example from theater that really impacted you in a positive way where you were the star—like, the story was about you! You got to embody the center of the story. And that was really powerful!

SA: And I was the German blonde-haired girl, right? Like, me! (laughs)

TSC: (laughs) Yeah, that's incredible. I love that story so much.

I want to know what your dreams and aspirations are for South Asians, Asian Americans, Asian diasporic spaces, and also the people who shape them through design.

TSC: Totally. Yeah, that's really powerful. I mean, I do think that I don't necessarily identify as a woman, but I do think I identify more as a woman of color. That feels more authentic to me. I’ve never really thought about that until you just told that history.

SA: Yeah! I think I heard that really interesting history about that—like, I can’t remember—it might have been in the seventies or something or sixties—where Black women were like, We're stronger together! Let's call everyone else! And so I love that. Of course, Black women are amazing. They're the ones who are the trailblazers with the solidarity work.

And there are amazing South Asians that do solidarity work. I know in India that they are tirelessly fighting against the institution—government institutions and corporations. I know there are amazing, amazing women. And so I think part of that is we aren't hearing those stories either, right? So part of that is that capitalism and white supremacy don’t want those stories to be revealed or to get the light of day. And I mean, I do know a lot of Indian women who do social justice work in India and also here as well. So I do think there's a group of us doing it. Yeah.

TSC: How would you describe your role in Dark Matter U? I want to talk about this a little bit more because I'm just curious how you feel in BIPOC spaces. There’s obviously racial dynamics that are still at play, and I’m always conscious of that saying that “you don't need white people to reproduce white supremacy.” I would just love to hear you talk a little more about your role. I know you run Office Hours and you're on the People team—

SA: I'm on the People slash Opportunity team. And I have kind of with Office Hours been a little bit delinquent, but I mean, for me, Dark Matter U, first of all, is a place for me to belong, and where I can kind of not have to explain myself, like, just be welcomed. But I see my role as supporting everyone and anyone there. I didn't have this support. And how can I be in solidarity with Black—especially Black, as well as, I would say, Indigenous (I don't know if we have Indigenous people) and Latino, Latine, Latinx, or Latina. So, I mean, to me, it’s to be an ally and to do the work. So I’m just constantly like, There's so much work that hasn't been done on behalf of supporting diversity in BIPOC. And so that's what I see my role is like—volunteering, doing what I can, supporting, stepping in when I can. Yeah, a hundred percent. Yeah, wherever I’m needed. A model of allyship for me is literally stepping in whenever I can, leveraging what knowledge, resources, privilege, anything—

TSC: And do you feel supported in the space?

SA: I do! I mean, I feel like I’m older. So I’m in a different place in my life. But I do feel like—I mean, like with you! Asking you, “Can you help me? Can you share your application?” Like, that was so, like—I don't have this sense of, “I'm an elder,” or whatever, even though I think I am an elder! Just by my age! (laughs)

TSC: (laughs) You’re not an elder. I mean, by how much I respect you, you’re an elder, but by age, you’re not an elder.

SA: (laughs) But that’s the thing! I love that I can learn with and from other people. I mean, that's the other thing, to be in solidarity, to learn with and from people, and to experience what it is to be in a space where, yeah—I would have never guessed that this is what it could be like for me. But yeah, I'm not sure myself what my role is, but I do think that I’m trying to support and fill in where needed. Yeah. And to leverage whatever power and privilege I can for the benefit of others.

TSC: Yeah. That’s beautiful.

SA: Yeah! Well, I wish someone—well, I have had people do this for me.

TSC: That teacher!

SA: Yeah, that teacher and other people who, like, saw me and saw the potential for me to do the work that I was trying to do, even though I didn't really even believe it myself. I've seen it happen with my daughter. My daughter has this great mentor, and she is just propelled—it’s like the power of mentorship is like—

TSC: It’s so real.

SA: It’s so real!

TSC: So real. Yeah, just feeling seen and even just somebody acknowledging you and validating you.

SA: Totally, yeah. Gretel! Being Gretel!

TSC: Yes! Gretel! That is so incredible and so funny, because I remember doing theater when I was very young. I was very outgoing, and really loud, and I just had a really big personality. I wouldn't say that I don't now, but I think I switch it up based on who I’m around. Because, you know, there were many years of teachers saying I was bossy, or writing my name on the board, all these things.

But I do remember getting cast in a lead role in middle school. And it was like a frog. I don't remember what the play was about, but I was the lead, and it was a frog, and I was super excited. But then, as I got older, the teachers stopped casting me as lead roles, and I think it’s because—at least I felt like it was because I was Asian.

SA: Yeah.

TSC: So I just think it's funny that you have an example from theater that really impacted you in a positive way where you were the star—like, the story was about you! You got to embody the center of the story. And that was really powerful!

SA: And I was the German blonde-haired girl, right? Like, me! (laughs)

TSC: (laughs) Yeah, that's incredible. I love that story so much.

I want to know what your dreams and aspirations are for South Asians, Asian Americans, Asian diasporic spaces, and also the people who shape them through design.

“I love being part of women of color. I love it! I think I’m always searching for places to belong.”

SA: Gosh! I just wish that we could be together and really fight against oppression and the internalized oppression and racism and colonialism. I really can see how colonialism has harmed us. And you know, I feel like we are trapped in this mindset. And casteism is another version of racism, and colorism and patriarchy—all of these things that have been passed down from a few of the people who colonized India.

I just came back from India, and one of the things that struck me was that they [men] separated men and women in the architecture. And I think that came from the Mughals, and so that's the story that gets told and passed down because that was fifteen hundred years ago about, I think. Over a thousand. I just see how mindsets in architecture that shape the built environment impact how people think. These conditions of oppression, and oppression over people—get manifested in architecture and space and actually they sustain and perpetuate. And really, my dream would be for South Asians to not get wrapped up into those stories—and be free! Yeah, the hold of racism is just so strong.

TSC: It’s so strong. And it's so deep inside each and every one of us that it feels impossible to escape sometimes. But we have to keep trying.

SA: Yeah, yeah. These are really great questions. Thank you.

TSC: No, thank you for your reflections!

So an important component of this project is creating resources that'll be useful for Asian and South Asian American designers and creatives. I wanted to ask you what resources you would love to see for other Asian designers, or what would you have loved to see as a younger South Asian designer?

SA: I’ll just refer back to this great workshop that I attended. It was a series, and one of the things that was really helpful was to identify the source of the internalized racism, like where it's born. It's not to give us an excuse, but it was so much easier for me to point to, like, because I’m like—I know I have these tendencies, but to actually understand where they were sourced historically, and how colorism, I mean, how color has really infused all of South Asian culture—I would say global culture quite honestly—whiteness, I suppose. And that was so helpful to me because just being able to have these conversations and not just be like, We need to turn to Black and Brown people, and always look to them. No, let's actually turn to each other and let's identify our own internal oppression and racism, and then maybe we can start to build a coalition, like a solidarity with each other, so that we can stop seeing us as being different, but really part of a system that's positioning us in these places.

And I don't know where that would sit. Where do you teach that? But I think, like, that would be—that's like Ethnic Studies, quite honestly. But I would love for that to be a part of the resources—like, what skills and tools and knowledge would be helpful in understanding why we are the way we are—like, all of these things that have been set up by whiteness. So that's something that I would find really useful. I don't know, like, what you're saying—resources for—

TSC: I love that. You answered the question perfectly. I’m thinking that some of these things really have to be about dialogue. It has to be more personal and one-on-one, which is a much slower process, but I think often more effective than saying, “Here's an educational pamphlet, or here's a lecture that I’m going to give about this.” Those are also useful and important—I’ve read books and pamphlets and heard lectures that I've found really impactful—but I do think that real transformation is much slower and more relational. I’m wondering how that could be a resource made available online. Maybe it's like, “Here's a workshop to do with yourself or with your community.” So I love that idea.

SA: I mean, I would love a resource to know the cultural holidays and how people celebrate them. I actually got a great newsletter that kind of just gave a list of all the dates for the holidays for the upcoming year. I'm like, This is great! Like, culturally sensitive information about how to wish someone, like—oh, by the way, Happy Lunar New Year!

TSC: Yes, Happy Lunar New Year.

SA: I feel like the more we know, the more solidarity we'll have. How can we bridge differences?

I think I told you I was visiting my daughter in Japan, and so she's been living there for three months, and you know it's just really interesting, because, as a tourist, there's only so much to do and see. There's lots of temples—you eat the food, you know—but, seeing how she has integrated herself in the culture and actually, you know, understanding why people do the things they do, and not seeing it as, “Oh, that's weird,” but more as, “Okay, this is actually a consistent way in which people—in which this culture engages in.”

But yeah, it'd be really nice to have, even as simple as, what are some of the cultural holidays? And how do you wish them? Like, don’t give this, give this, right? Don’t give things in four. (laughs) Don't give four things to, you know—

TSC: Oh, you mean for Chinese people?

SA: For Chinese people, yeah.

TSC: Yeah! That's funny.

SA: Because I think the symbol, right, is death?

TSC: The word “four,” sì, sounds like “death,” which is sǐ. Chinese people are very superstitious, and there are a lot of words that sound similar, so, things that sound like “money,” are lucky.

But yeah, it's funny because my birthday is super unlucky. I was born on the fourteenth, and I always felt so bad for my parents, because “fourteen,” shí sì, gives the four an even stronger emphasis and sounds like “is dead.”

SA: That’s funny! But you know, for us, you know, how do we build that? And maybe it's because my mindset is more curious—like, I'm really interested to know, like, I would love to come to someone's house and bring something that was culturally appropriate, right? I don't know; I would just love to do that. And I think, that’s a simple thing, but I don't know. Do you have any ideas for resources? I'm curious.

TSC: Well, yeah! But, okay, first I want to talk about this holidays thing because I’m curious how it would translate into something spatial. I mean, I know architects are always trying to make things spatial. And one thing all architects should probably learn is that not everything has to be solved through architecture. But, if we were to think about it being a resource that is somehow spatial or architectural, I’m curious what that would look like.

SA: Well, I mean, are there designs—like, I went to India, and I visited many of my relatives who have joined families. Like, understanding that living with your in-laws or your parents is actually a very normal thing. And they had kind of changed the design of their house to accommodate that, you know? People were sharing rooms, like, just understanding that there are cultural norms that we’re not used to and it's based in culture, right? It's not like, oh, every house is going to be shared, but more like, how do you create a house, or how you create space that is intergenerational. I feel like that's something that we don't think about. We're very nuclear.

Building around the lunar calendar or something—I love that prompt, though. How would you take that into account?

I kind of feel like it's about flexibility of space. So, when in CCA’s back campus, one of the things that I keep thinking would be so easy would be to identify space that's a flexible space for Native Americans to go and have their ceremony. And I was like, How easy would that have been for the design to just say, this is a space for ritual and ceremony and celebration, and it starts with the Native Americans.

Could you imagine if there was a space in the Bay Area all of a sudden, where you can light a fire and you can make noise, and you can be indoor/outdoor? Could you imagine a culturally open space where you could have your ceremonies? Because right now, they are just celebrated in the house, or sometimes a community center, which is, again, not bad. But if there was a space to allow you to be, to reflect your culture and the holiday that it represents in the celebration. I don't know—that would be so awesome.

TSC: Yeah. You're making me think about so many things—the intergenerational living, being able to have a space for prayer or ceremonies at school. I mean, we talked about this in our DMU workshop a little bit.

And I’m also thinking about the holidays, too, because I was talking to one of my friends who is Chinese and we were both saying how we didn't really grow up celebrating a lot of our holidays and a lot of it was because we didn't have the day off, so we actually didn't know about a lot of our traditions. And so there's also this other feeling of not feeling like you are enough. Not feeling like you are Asian enough, or Chinese enough, or Taiwanese enough, or South Asian enough, or whatever it is. And it’s because we just literally weren't given the space—and the spaces to acknowledge those traditions. And so it's just making me think that there actually is a really strong connection between holidays and space because I think you learn so much about a culture from how the people celebrate and what they do in times of celebration and convening.

SA: Yes! Yeah. I was in Japan during New Year’s, and there are what feels like thousands of temples all over country, and there are both shrines and temples. And at every single one of them, there were these long lines where—and I don't know if this is something you're familiar with—you throw the coin, you clap twice, you bow, you kind of say a prayer, and then—or you clap once, and then you say a prayer, and then you clap twice or something. And basically, it's like casting a New Year's wish and New Year's is celebrated for two weeks!

TSC: Oh, wow!

SA: So for two weeks there were these lines of people who were doing this. And I did multiple of them. It was so great! (laughs) And it was so simple, and it was on your way to some place, and you would just go and stand in these lines and they would go very quickly. But it just made me realize, Oh, in the US, we have a party, we count down, and it's done! Like, it's one night, and it's done! And this other culture—it’s like two weeks! And I thought New Year’s was like a US thing, or you know, kind of a Western European thing, and I’m like, Wow, they really—and the young women will dress in the beautiful kimonos. And so you have this very—there was just all this stuff that I’m like, Wow! You would not think that this would be acceptable in normal times, but it's very interesting to see how people celebrate the culture and learn so much from them and their values, and what’s important.

TSC: Yeah, that is very American to be like, It’s one night! We're just going to party really hard and then go back to work. (laughs)

I want to be mindful of time, but I’ll just ask one more question, which is: Is there anything else that you want to share, or that you want to revisit?

SA: Not right now. Thank you so much. I wish this was a two-way conversation. Because it's the shared experience, right? It's like the fact that you're asking these questions, which, in essence, were never that important to anyone ever. So I'm really just thankful for you asking these questions. And yeah, I mean, I am just really humbled. So—thank you so much. I think I've spoken enough. (laughs)

TSC: Oh, no, never! I think that's a tendency for Asians to be like, I’m taking up too much space! But with this project I’m saying, “You take up that space!”

SA: Yeah, thank you.

I just came back from India, and one of the things that struck me was that they [men] separated men and women in the architecture. And I think that came from the Mughals, and so that's the story that gets told and passed down because that was fifteen hundred years ago about, I think. Over a thousand. I just see how mindsets in architecture that shape the built environment impact how people think. These conditions of oppression, and oppression over people—get manifested in architecture and space and actually they sustain and perpetuate. And really, my dream would be for South Asians to not get wrapped up into those stories—and be free! Yeah, the hold of racism is just so strong.

TSC: It’s so strong. And it's so deep inside each and every one of us that it feels impossible to escape sometimes. But we have to keep trying.

SA: Yeah, yeah. These are really great questions. Thank you.

TSC: No, thank you for your reflections!

So an important component of this project is creating resources that'll be useful for Asian and South Asian American designers and creatives. I wanted to ask you what resources you would love to see for other Asian designers, or what would you have loved to see as a younger South Asian designer?

SA: I’ll just refer back to this great workshop that I attended. It was a series, and one of the things that was really helpful was to identify the source of the internalized racism, like where it's born. It's not to give us an excuse, but it was so much easier for me to point to, like, because I’m like—I know I have these tendencies, but to actually understand where they were sourced historically, and how colorism, I mean, how color has really infused all of South Asian culture—I would say global culture quite honestly—whiteness, I suppose. And that was so helpful to me because just being able to have these conversations and not just be like, We need to turn to Black and Brown people, and always look to them. No, let's actually turn to each other and let's identify our own internal oppression and racism, and then maybe we can start to build a coalition, like a solidarity with each other, so that we can stop seeing us as being different, but really part of a system that's positioning us in these places.

And I don't know where that would sit. Where do you teach that? But I think, like, that would be—that's like Ethnic Studies, quite honestly. But I would love for that to be a part of the resources—like, what skills and tools and knowledge would be helpful in understanding why we are the way we are—like, all of these things that have been set up by whiteness. So that's something that I would find really useful. I don't know, like, what you're saying—resources for—

TSC: I love that. You answered the question perfectly. I’m thinking that some of these things really have to be about dialogue. It has to be more personal and one-on-one, which is a much slower process, but I think often more effective than saying, “Here's an educational pamphlet, or here's a lecture that I’m going to give about this.” Those are also useful and important—I’ve read books and pamphlets and heard lectures that I've found really impactful—but I do think that real transformation is much slower and more relational. I’m wondering how that could be a resource made available online. Maybe it's like, “Here's a workshop to do with yourself or with your community.” So I love that idea.

SA: I mean, I would love a resource to know the cultural holidays and how people celebrate them. I actually got a great newsletter that kind of just gave a list of all the dates for the holidays for the upcoming year. I'm like, This is great! Like, culturally sensitive information about how to wish someone, like—oh, by the way, Happy Lunar New Year!

TSC: Yes, Happy Lunar New Year.

SA: I feel like the more we know, the more solidarity we'll have. How can we bridge differences?

I think I told you I was visiting my daughter in Japan, and so she's been living there for three months, and you know it's just really interesting, because, as a tourist, there's only so much to do and see. There's lots of temples—you eat the food, you know—but, seeing how she has integrated herself in the culture and actually, you know, understanding why people do the things they do, and not seeing it as, “Oh, that's weird,” but more as, “Okay, this is actually a consistent way in which people—in which this culture engages in.”

But yeah, it'd be really nice to have, even as simple as, what are some of the cultural holidays? And how do you wish them? Like, don’t give this, give this, right? Don’t give things in four. (laughs) Don't give four things to, you know—

TSC: Oh, you mean for Chinese people?

SA: For Chinese people, yeah.

TSC: Yeah! That's funny.

SA: Because I think the symbol, right, is death?

TSC: The word “four,” sì, sounds like “death,” which is sǐ. Chinese people are very superstitious, and there are a lot of words that sound similar, so, things that sound like “money,” are lucky.

But yeah, it's funny because my birthday is super unlucky. I was born on the fourteenth, and I always felt so bad for my parents, because “fourteen,” shí sì, gives the four an even stronger emphasis and sounds like “is dead.”