“We are here. This is our home. So the most important thing is that we have to create roots, and we have to create a sense of belonging here. But we will always remain in multiple pluralities.”

she/her

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I’m here with Shundana Yusaf for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora.

I’m interested to hear about your family background and your experience growing up in Pakistan. Can you describe the neighborhood, the village, the community you grew up in? What was your family home like?

Shundana Yusaf (SY): So I grew up in multiple places at the same time. I grew up in Pakistan in a city near the border of Afghanistan called Peshawar. Our village is two hours away from the city, so every weekend, all of my childhood, we would go there, and then the summer holidays and the winter break, we would go there. So we lived in these kind of two realities—very, very radically different. One, very, very cosmopolitan, very modern, very urban with people speaking multiple languages, me going to one of the elite schools. And then going to the village where we were interacting with cows, younger kids, donkeys, squeezing sugar canes, running around in the fields and people living in very different types of architectural settings. My dad was in the Air Force, so we lived in Saudi Arabia. We lived in many different parts of Pakistan, mostly in Air Force cantonments.

TSC: What was the experience like for you when you first arrived in the US for graduate school? Did you find it challenging in any way? Did you feel isolated or disconnected from your home or your life in Pakistan?

SY: I came to grad school at GSD at Harvard, where I experienced a year of imposter syndrome. But at the end of the year, somehow, I got over it. I got a job very quickly over here, but I had a lot of difficulty adjusting to the office culture. Number one, there is the difference in work environments. In Pakistan, I was doing entirely turnkey design projects. Most of the work that I was doing was residential work for people who were my parents’ friends or our family members. I had more work than I could manage. I did not have to work with other architects. I had a lot of options in Pakistan. I was teaching already in Pakistan after my undergraduate. I was doing design work as well as grants—we were building the primary schools in rural areas and developing a new model of delivering these projects in rural as well as in urban communities. So it was K though four.

Then in the US, what happened was the sharp contrast to working in very small either rural communities, very elite residential projects in Pakistan. Coming from that suddenly tuned to the world of high theory Marxist discourse, I found it at once very liberating from the kind of very practical and myopic work that I was doing in design in Pakistan. But, at the same time, very disorienting because none of that work was talking to the challenges of design practice in the Global South. It was all directed towards the question of housing in Boston, the question of capitalism, socialism, and obviously a postmodern discourse on pastiche and quotation and the question of history which kind of really made me at once feel very alienated from what I was reading, but also very excited that I was entering into very different worlds. So I had all these kind of always living in these two dualities of experiences. Loving it and feeling alienated from it, and impatient with the fact that it wasn’t speaking to the questions that I had and didn’t allow me to theorize. They didn’t give me the language or the skills to theorize the things that I wanted to work on.

TSC: Did you always know that you wanted to come to the US to study? Were there a lot of people from where you grew up who came here? How did you even end up here?

SY: I had absolutely no intention of coming to the US. There was both a personal and a professional issue. Two reasons because of which I ended up here: one was that I felt very stifled in doing the kind of applied, hands-on work that I was doing in Pakistan, which wasn’t allowing me to theorize that work and understand the larger import of architectural practice in this particular historical moment for a young woman who’s working in a very, very patriarchal context. But because the construction staff that I was working with was all relatively less school-educated, working-class people, it was very easy for me to maneuver that. But I hit a ceiling. I learned a lot from them, but at some point, I felt there was no way further. I was desperately in need of mentorship, and I felt that anybody who could mentor me in Pakistan already had mentored me—that I knew of.

The other reason was more personal: that I had a lot of difficulty navigating the way I wanted to develop my personal and professional life and the way my parents envisioned it. I felt kind of very claustrophobic about that. So it was to get out of both the myopia of my work but also the kind of suffocating environment for a young woman in architecture profession that made it very difficult for me to stay there.

TSC: That’s really interesting. I know you’ve talked to me about how your racialization in this country doesn’t really affect you and how you don’t really identify with the racial trauma experienced by your BIPOC colleagues and friends and even your daughter. Why do you think that is? And how would you describe your experience with your racial identity in your work and in your everyday life? It’s interesting to hear you say that you wanted to escape something that felt suffocating to you. I think, often, children of immigrants who grow up here will wonder why their parents left and also what it would be like if they hadn’t left.

SY: In the United States, race is primary concept of dividing people and their experience. But it is not a political or intellectual concept in Pakistan. Language is. We are linguistic groups. And I come from a language group that is not as successful in Pakistan, as prominent as the other ones, but it’s in the middle. So it’s not too low, not too high kind of things. But I come from a lot of privilege within Pakistan. I went to the best schools—I went to the best universities, and somehow until I came to the US and where I snapped and had to leave Pakistan, I was able to maneuver the controls over my gender by trying to use education as a legitimate way out of it. So, like, for my family, education was very valuable both for women and for men, but for women to a certain extent.

After that, you hit the ceiling. You have to get married—you have to produce children, and your focus has to be that. I was never averse to it, but I could not take my mother’s generation as the role model for that, though my mother’s generation also had a lot of really wonderful emancipated women who were feminists. But I did not have a lot of feminists in my family. So my problems were more gender related than race related.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I’m here with Shundana Yusaf for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora.

I’m interested to hear about your family background and your experience growing up in Pakistan. Can you describe the neighborhood, the village, the community you grew up in? What was your family home like?

Shundana Yusaf (SY): So I grew up in multiple places at the same time. I grew up in Pakistan in a city near the border of Afghanistan called Peshawar. Our village is two hours away from the city, so every weekend, all of my childhood, we would go there, and then the summer holidays and the winter break, we would go there. So we lived in these kind of two realities—very, very radically different. One, very, very cosmopolitan, very modern, very urban with people speaking multiple languages, me going to one of the elite schools. And then going to the village where we were interacting with cows, younger kids, donkeys, squeezing sugar canes, running around in the fields and people living in very different types of architectural settings. My dad was in the Air Force, so we lived in Saudi Arabia. We lived in many different parts of Pakistan, mostly in Air Force cantonments.

TSC: What was the experience like for you when you first arrived in the US for graduate school? Did you find it challenging in any way? Did you feel isolated or disconnected from your home or your life in Pakistan?

SY: I came to grad school at GSD at Harvard, where I experienced a year of imposter syndrome. But at the end of the year, somehow, I got over it. I got a job very quickly over here, but I had a lot of difficulty adjusting to the office culture. Number one, there is the difference in work environments. In Pakistan, I was doing entirely turnkey design projects. Most of the work that I was doing was residential work for people who were my parents’ friends or our family members. I had more work than I could manage. I did not have to work with other architects. I had a lot of options in Pakistan. I was teaching already in Pakistan after my undergraduate. I was doing design work as well as grants—we were building the primary schools in rural areas and developing a new model of delivering these projects in rural as well as in urban communities. So it was K though four.

Then in the US, what happened was the sharp contrast to working in very small either rural communities, very elite residential projects in Pakistan. Coming from that suddenly tuned to the world of high theory Marxist discourse, I found it at once very liberating from the kind of very practical and myopic work that I was doing in design in Pakistan. But, at the same time, very disorienting because none of that work was talking to the challenges of design practice in the Global South. It was all directed towards the question of housing in Boston, the question of capitalism, socialism, and obviously a postmodern discourse on pastiche and quotation and the question of history which kind of really made me at once feel very alienated from what I was reading, but also very excited that I was entering into very different worlds. So I had all these kind of always living in these two dualities of experiences. Loving it and feeling alienated from it, and impatient with the fact that it wasn’t speaking to the questions that I had and didn’t allow me to theorize. They didn’t give me the language or the skills to theorize the things that I wanted to work on.

TSC: Did you always know that you wanted to come to the US to study? Were there a lot of people from where you grew up who came here? How did you even end up here?

SY: I had absolutely no intention of coming to the US. There was both a personal and a professional issue. Two reasons because of which I ended up here: one was that I felt very stifled in doing the kind of applied, hands-on work that I was doing in Pakistan, which wasn’t allowing me to theorize that work and understand the larger import of architectural practice in this particular historical moment for a young woman who’s working in a very, very patriarchal context. But because the construction staff that I was working with was all relatively less school-educated, working-class people, it was very easy for me to maneuver that. But I hit a ceiling. I learned a lot from them, but at some point, I felt there was no way further. I was desperately in need of mentorship, and I felt that anybody who could mentor me in Pakistan already had mentored me—that I knew of.

The other reason was more personal: that I had a lot of difficulty navigating the way I wanted to develop my personal and professional life and the way my parents envisioned it. I felt kind of very claustrophobic about that. So it was to get out of both the myopia of my work but also the kind of suffocating environment for a young woman in architecture profession that made it very difficult for me to stay there.

TSC: That’s really interesting. I know you’ve talked to me about how your racialization in this country doesn’t really affect you and how you don’t really identify with the racial trauma experienced by your BIPOC colleagues and friends and even your daughter. Why do you think that is? And how would you describe your experience with your racial identity in your work and in your everyday life? It’s interesting to hear you say that you wanted to escape something that felt suffocating to you. I think, often, children of immigrants who grow up here will wonder why their parents left and also what it would be like if they hadn’t left.

SY: In the United States, race is primary concept of dividing people and their experience. But it is not a political or intellectual concept in Pakistan. Language is. We are linguistic groups. And I come from a language group that is not as successful in Pakistan, as prominent as the other ones, but it’s in the middle. So it’s not too low, not too high kind of things. But I come from a lot of privilege within Pakistan. I went to the best schools—I went to the best universities, and somehow until I came to the US and where I snapped and had to leave Pakistan, I was able to maneuver the controls over my gender by trying to use education as a legitimate way out of it. So, like, for my family, education was very valuable both for women and for men, but for women to a certain extent.

After that, you hit the ceiling. You have to get married—you have to produce children, and your focus has to be that. I was never averse to it, but I could not take my mother’s generation as the role model for that, though my mother’s generation also had a lot of really wonderful emancipated women who were feminists. But I did not have a lot of feminists in my family. So my problems were more gender related than race related.

Interview Segment: What someone like me should be working on.

INTERVIEW 05 DETAILS

Narrator:

Shundana Yusaf, she/her

Interview Date:

February 13, 2023

Keywords:

Themes: South Asian identity, Pakistani identity, rural communities, gender, feminism, language, class, immigrant experience, generational differences, microaggressions, feminist histories, oral cultures, Islam, scholarship, architectural education, sound, noise, Muslim, mentorship, Indigenous knowledge, trust building, knowledge production

Places: Pakistan, Peshawar, Harvard GSD, Britain, Hagia Sophia, Navajo Nation, University of Utah School of Architecture

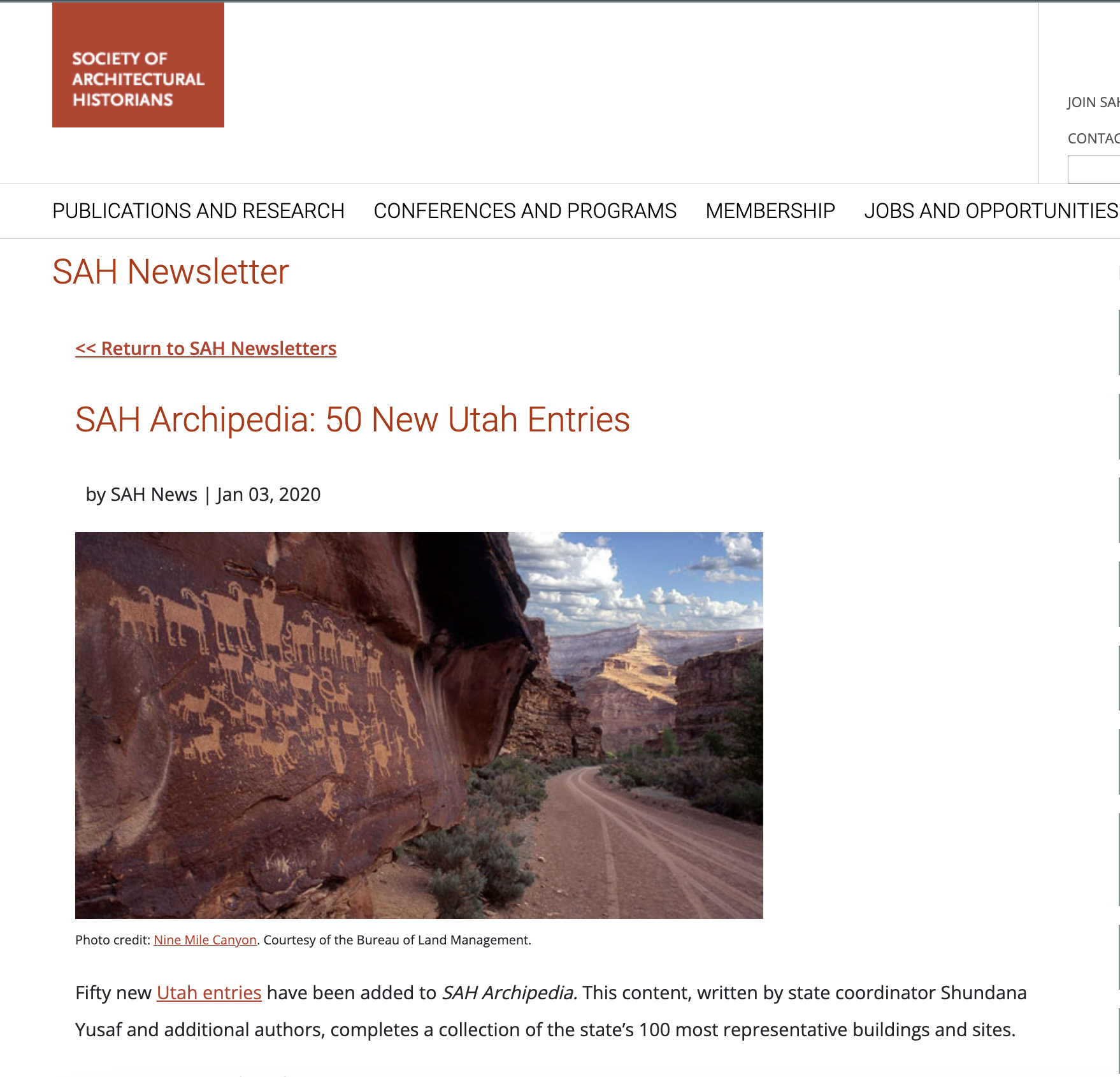

References: Nááts'íilid Initiative, DesignBuildBLUFF, Archipedia Utah, Society of Architectural Historians, Clark Institute, Association of Asia Scholars

ABOUT SHUNDANA

Ancestral Land:

Northwestern Pakistan

Homeland:

Pakistan

Current Land:

Shoshone, Paiute, Goshute, and Ute

(Salt Lake City, Utah)

Diaspora Story:

I moved to the US at the age of 27 for grad school in Cambridge, Massachusetts. I have a rich network of first cousins with very different immigrant experiences. I made friends with both South Asian and non-South Asian students. Over the years, I have become comfortable with finding camaraderie with all sorts of decolonial activists in the global north and south alike.

Creative Fields:

Architecture and Architectural History

Racial Justice Affiliations:

Nááts'íilid Initiative

Favorite Fruit:

Pomegranate

Biography:

Shundana Yusaf is an Associate Professor of History and Theory at the School of Architecture, University of Utah. Her scholarship in architectural history and theory, juxtaposes colonial/ postcolonial history with sound studies, framing each as a force of globalization. She is involved in a pedagogic initiative called ‘Decolonizing Architectural Pedagogy.’ She is currently a fellow at Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts where she is completing a book entitled Resonant Tomb: A Feminist History of Sufi Shrines in Pakistan. She is the founding member of Nááts'íilid Initiative.

I would also insist that race—in Pakistan, race and language don’t have

the trauma that you have in the United States or even in Europe, like in the West.

So when I look at the

challenges that my daughter has gone through as a young person growing up in a

very, very conservative white state and a very non-diverse state—a

predominantly monotone kind of state—she hasn’t really experienced large

traumas, but what she has experienced is death by a thousand cuts. Because

they’re like these microaggressions, very small aggressions. I feel that

because she has experienced them from childhood onwards, and that’s the primary

reality she has known because she has lived in multiple places, and we travel a

lot, and we go to Pakistan every year regularly. So I think that is one

difference that I did not have to go through these things as a child.

I am conscious of them now as an adult, but I have not experienced any, even microaggression towards me. So what I’m saying is I have not witnessed it in myself, somebody acting upon somebody else, and I have not witnessed it on myself. I have only heard about it secondhand. So, while I can empathizewith it, while I can create allyship with it, I can’t claim to have experienced it. And to claim that I am a BIPOC person like Samantha or Kassie, for example—there is no comparison between the experiences and the family challenges and all the kind of distrust that they have to have because of the intergenerational trauma that they have experienced. My daughter has the same, but hers is not intergenerational at least. So she and you are in the same class of people as opposed to your parents, whom I regard to be like myself.

TSC: Do you think it could be that you have not witnessed it or that you are not tuned in to it? Like, you don’t notice it? Do you think that could be a more accurate way to describe it? Because in comparing my experience to that of your daughter, I would say that I’ve witnessed several microaggressions towards my parents, but I don’t think they notice it. And that makes me angry.

SY: And that is quite possible—which is also a privilege! (laughs)

TSC: (laughs) Yeah.

SY: Ignorance is bliss, right? So it’s quite, quite possible! At least I haven’t heard it from Cherie, from my daughter. She has witnessed the kind of things that I have heard from you about you as a child experiencing certain kind of attitudes and turn of phrase or kind of like a small snicker or something that feels really, really large at different ages, right? I think as we grow older, and because I came to this country at the age of twenty-seven, my political consciousness was already quite formed. So my political conscious is not formed in the United States, despite this fact that now I’ve lived almost as many years in the US as I have in Pakistan. But I dogenuinely believe that the disability to recognize it is also a kind of power.

Ignorance and forgetfulness has its own power. So the fact that it has not paralyzed me in any ways, right? I’m not saying that these things don’t happen. I see it in job searches. I see it in awarding of grants, things like that. When I was working on a European topic, there was no reception of my work in the United States. All of it was only in England. And mostly there was a lot of negative critique of my work saying, “How can somebody who doesn’t know England write about England?” As if they know about the England of 1927. And that, “How dare she talk about from the outside?”—and blah-blah-blah. But I have never in my book made an argument that I was talking from within, right? I always position myself in all of my work.

But now that I’m working on Islam, suddenly everybody and their mother-in-laws knows about my work. I’m getting invited to places both in the US, Europe, Asia, Africa, as well as Australia and South America. Suddenly, there’s a lot of recognition of my work; invitations are coming; people interested in knowing where I’m headed. That is the first time that I’m noticing that, Oh, now I am working on something that people understand that someone like me should be working on. When Brits work on South Asia, everybody thinks, Oh, it’s a particular kind of scholarship. But when South Asians work on Britain, which was my first book, it was considered very “liberal” to read it on its own terms. A lot of conservative scholars and architects kind of looked with a very “humph!” attitude towards my work.

TSC: I mean, what you’re describing is very much a microaggression on a larger scale! (laughs) When working on history that is about white people as a non-white person—did you feel pressure to appear more neutral in your position?

I am conscious of them now as an adult, but I have not experienced any, even microaggression towards me. So what I’m saying is I have not witnessed it in myself, somebody acting upon somebody else, and I have not witnessed it on myself. I have only heard about it secondhand. So, while I can empathizewith it, while I can create allyship with it, I can’t claim to have experienced it. And to claim that I am a BIPOC person like Samantha or Kassie, for example—there is no comparison between the experiences and the family challenges and all the kind of distrust that they have to have because of the intergenerational trauma that they have experienced. My daughter has the same, but hers is not intergenerational at least. So she and you are in the same class of people as opposed to your parents, whom I regard to be like myself.

TSC: Do you think it could be that you have not witnessed it or that you are not tuned in to it? Like, you don’t notice it? Do you think that could be a more accurate way to describe it? Because in comparing my experience to that of your daughter, I would say that I’ve witnessed several microaggressions towards my parents, but I don’t think they notice it. And that makes me angry.

SY: And that is quite possible—which is also a privilege! (laughs)

TSC: (laughs) Yeah.

SY: Ignorance is bliss, right? So it’s quite, quite possible! At least I haven’t heard it from Cherie, from my daughter. She has witnessed the kind of things that I have heard from you about you as a child experiencing certain kind of attitudes and turn of phrase or kind of like a small snicker or something that feels really, really large at different ages, right? I think as we grow older, and because I came to this country at the age of twenty-seven, my political consciousness was already quite formed. So my political conscious is not formed in the United States, despite this fact that now I’ve lived almost as many years in the US as I have in Pakistan. But I dogenuinely believe that the disability to recognize it is also a kind of power.

Ignorance and forgetfulness has its own power. So the fact that it has not paralyzed me in any ways, right? I’m not saying that these things don’t happen. I see it in job searches. I see it in awarding of grants, things like that. When I was working on a European topic, there was no reception of my work in the United States. All of it was only in England. And mostly there was a lot of negative critique of my work saying, “How can somebody who doesn’t know England write about England?” As if they know about the England of 1927. And that, “How dare she talk about from the outside?”—and blah-blah-blah. But I have never in my book made an argument that I was talking from within, right? I always position myself in all of my work.

But now that I’m working on Islam, suddenly everybody and their mother-in-laws knows about my work. I’m getting invited to places both in the US, Europe, Asia, Africa, as well as Australia and South America. Suddenly, there’s a lot of recognition of my work; invitations are coming; people interested in knowing where I’m headed. That is the first time that I’m noticing that, Oh, now I am working on something that people understand that someone like me should be working on. When Brits work on South Asia, everybody thinks, Oh, it’s a particular kind of scholarship. But when South Asians work on Britain, which was my first book, it was considered very “liberal” to read it on its own terms. A lot of conservative scholars and architects kind of looked with a very “humph!” attitude towards my work.

TSC: I mean, what you’re describing is very much a microaggression on a larger scale! (laughs) When working on history that is about white people as a non-white person—did you feel pressure to appear more neutral in your position?

“So

when I look at the challenges that my daughter has gone through as a young

person growing up in a very, very conservative white state and a very

non-diverse state—a predominantly monotone kind of state—she hasn’t really

experienced large traumas, but what she has experienced is death by a

thousand cuts. Because they’re like these microaggressions, very small

aggressions.

”

SY: No. The way I wrote on white people’s histories, or what I would say—I

wrote about it as my history because I was part of the empire. I very

much position myself—how British architectural discourse on the radio and sound

studies looks like bringing in the kind of sensitivities coming from a

predominantly oral society allows me to do this work. And looking at the Global North from Global South—looking at the mothership from the periphery. I wrote it very clearly

like that, but I also insisted that I don’t want to do reverse orientalism,

right? I don’t want to write a history of the Occident from the Orient. So I felt that I had to look at very particular types of models of

scholarship that I was looking at. My book has been very well reviewed, but almost every book

review dealt with the fact that I am an American scholar of South Asian descent,

which is not what happens when necessarily somebody works on China who is an

American scholar; they just call it American scholarship. But I find it

actually a very good thing that it is the model that everybody should approach

right now—that we have to place our politics, identities, and research

methods on the table. So what is required of me should be required of everyone—or

what I require of myself should be required of everyone. But we are still not

there.

TSC: So many good points. It’s interesting to hear that once you started working on something in which the rest of the world deemed you should be working on based on your identity, you started getting more reception and more success, and people are respecting you more. What prompted or inspired you to work on Islam? Can you tell me a little bit more about that project and what it has been like for you to work on it?

SY: So, when I worked on Britain, a lot of people—and when my book came out, it wasn’t people anywhere in the West; it wasn’t people in Europe; it wasn’t people in the US but people like my colleagues, my old schoolmates, my family members—everybody who reads—saying that I had spent a lot of time working on material that did not address the kind of questions that were theirday-to-day questions. So I felt that, Oh, I did what actually you are doing right now in this particular project supported by the Graham grant, which is, What are the issues that are of interest to me? So I always felt that one of the biggest challenges in art and architectural history, whether it is of Islam, of the West, of the East, was that the focus on architecture as a visual art actually makes it very difficult to write about most of the people who are not elite people but who interact with and participate in the production and reproductionof spaces that are either elite spaces, monumental spaces, religious spaces.

So what is the negotiation of power from subaltern classes? And then obviously within subaltern classes, I was particularly interested in working on gender because it is something that I felt that I have had to navigate, and I did not have a language for it within architecture and architectural production. People talk about, Oh, women architects, blah, blah, blah. But the problem with women architects in South Asia and in Pakistan in particular—I can’t speak for Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Burma, or India. But I can speak for Pakistan—that women architects are expected to assimilate and have to masculinize themselves and their practice rather than use their knowledge and their experiences and their ways of being in the world as a way to de-masculinize architecture, or to neutralize architecture and to make it kind of women’s knowledge system as well.

So I think sound gave me a vehicle to talk about how women through their auditory practices reproduce a given space that is patriarchal, masculine, sometimes imperial, sometimes states. But it’s controlled by men and women who go and reproduce these spaces and repurpose them for themselves and the ingenious ways in which they use sound to occupy space. One of the things that you might be interested in—and actually some of the work that you are doing is very exciting to me on preservation—is that I’m looking at how sound, singing, oral storytelling year after year for a thousand years have been ways in which oral cultures do historic preservations. So this topic has allowed me to do placeknowing, placemaking through the tools that I had developed while working on Europe by looking at sound, radio, and architecture. And now I’m looking at which was really a kind of post-humanist conditions because electronic worlds—and now I’m looking at medieval to modern, to postmodern spaces in South Asia. So it’s a long seven hundred, eight hundred years of project.

So I think it’s a project in which all the tools that I developed from working and learning in the West, developing scholarly skills and research skills and research methods working on Europe, working in United States, and working on affluent societies—how I can take those skills. But now I’m a senior enough scholar that I can actually now remake them, dismantlethem, open them up, and take the toolbox and make literally new tools out of them. So it’s not that I’m working from scratch at all. But what I’m doing is, I take a tool: it doesn’t work, and then I have to remake the tool, which I could not do when I was twenty-seven. But now that I’m older and have a lot of writing behind me, it’s much easier to do that kind of work. I don’t think that I could have done this work. Other people have done it. I could not have done it because it would’ve made me a South Asian scholar, and that is something that I really, really feared. My friends have loved it, but I feared very much of being ghettoized.

TSC: Okay. You just said a lot. I think that a lot of designers who identify even deeply as people of color actually really want to just be recognized for their design ability first, and their identity second—even if their work is all about communities who share their racial identity or all about design justice, racial justice. I think that people still want to be recognized—as everybody else—as a brilliant designer. Full stop.

SY: As a fullness of their humanity, right?

TSC: Exactly. Exactly.

SY: Fear of ghettoization is what your Asian colleagues shared with me, which is that we want to work on our cultures, but we want to work it in a way that makes it part of the mainstream canonical discourse as opposed to onlyfor the experts in that area because that then becomes a defeatist project—for me. It’s not the case for everyone, but for me, it is a defeating project. Other people are doing fantastic work in that, but these are my own angst and my own—(laughs)

TSC: What do you mean by “defeatist project”?

SY: My fear is that—look, Tonia—I teach in a school of architecture. If I work on South Asia, the students will not be able to come to me and see me as somebody who can help them on doing something in Seattle or solving a housing problem here, or an LGBTQ problem in Utah or in Colorado or something like that, or the contemporariness. So I want to be able to come across to them as somebody who can speak to their concerns because that is my number-one constituency with whom I have on a daily basis a discourse—not only the discourse in writing. So that is what I feel that if my colleagues who—a lot of them who are in the art history departments—they have a bit more freedom because there’s a French scholar, there’s an eighteenth-century-Caribbean scholar, there’s this, that. So the whole department is like that. So the world is a collage—scholarship is a collage of all these things. That’s not the case in architecture schools. Architecture schools are very present minded and very now minded and very naval gazing. So it is about the particular locality, and that is partly the nature of how architecture as a discipline has evolved here where I’m teaching. So that is my fear.

TSC: Hmm. Yeah. Something else I wanted to ask you about is that you said you were talking about taking apart tools and reworking them. Can you give me an example of one?

TSC: So many good points. It’s interesting to hear that once you started working on something in which the rest of the world deemed you should be working on based on your identity, you started getting more reception and more success, and people are respecting you more. What prompted or inspired you to work on Islam? Can you tell me a little bit more about that project and what it has been like for you to work on it?

SY: So, when I worked on Britain, a lot of people—and when my book came out, it wasn’t people anywhere in the West; it wasn’t people in Europe; it wasn’t people in the US but people like my colleagues, my old schoolmates, my family members—everybody who reads—saying that I had spent a lot of time working on material that did not address the kind of questions that were theirday-to-day questions. So I felt that, Oh, I did what actually you are doing right now in this particular project supported by the Graham grant, which is, What are the issues that are of interest to me? So I always felt that one of the biggest challenges in art and architectural history, whether it is of Islam, of the West, of the East, was that the focus on architecture as a visual art actually makes it very difficult to write about most of the people who are not elite people but who interact with and participate in the production and reproductionof spaces that are either elite spaces, monumental spaces, religious spaces.

So what is the negotiation of power from subaltern classes? And then obviously within subaltern classes, I was particularly interested in working on gender because it is something that I felt that I have had to navigate, and I did not have a language for it within architecture and architectural production. People talk about, Oh, women architects, blah, blah, blah. But the problem with women architects in South Asia and in Pakistan in particular—I can’t speak for Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Burma, or India. But I can speak for Pakistan—that women architects are expected to assimilate and have to masculinize themselves and their practice rather than use their knowledge and their experiences and their ways of being in the world as a way to de-masculinize architecture, or to neutralize architecture and to make it kind of women’s knowledge system as well.

So I think sound gave me a vehicle to talk about how women through their auditory practices reproduce a given space that is patriarchal, masculine, sometimes imperial, sometimes states. But it’s controlled by men and women who go and reproduce these spaces and repurpose them for themselves and the ingenious ways in which they use sound to occupy space. One of the things that you might be interested in—and actually some of the work that you are doing is very exciting to me on preservation—is that I’m looking at how sound, singing, oral storytelling year after year for a thousand years have been ways in which oral cultures do historic preservations. So this topic has allowed me to do placeknowing, placemaking through the tools that I had developed while working on Europe by looking at sound, radio, and architecture. And now I’m looking at which was really a kind of post-humanist conditions because electronic worlds—and now I’m looking at medieval to modern, to postmodern spaces in South Asia. So it’s a long seven hundred, eight hundred years of project.

So I think it’s a project in which all the tools that I developed from working and learning in the West, developing scholarly skills and research skills and research methods working on Europe, working in United States, and working on affluent societies—how I can take those skills. But now I’m a senior enough scholar that I can actually now remake them, dismantlethem, open them up, and take the toolbox and make literally new tools out of them. So it’s not that I’m working from scratch at all. But what I’m doing is, I take a tool: it doesn’t work, and then I have to remake the tool, which I could not do when I was twenty-seven. But now that I’m older and have a lot of writing behind me, it’s much easier to do that kind of work. I don’t think that I could have done this work. Other people have done it. I could not have done it because it would’ve made me a South Asian scholar, and that is something that I really, really feared. My friends have loved it, but I feared very much of being ghettoized.

TSC: Okay. You just said a lot. I think that a lot of designers who identify even deeply as people of color actually really want to just be recognized for their design ability first, and their identity second—even if their work is all about communities who share their racial identity or all about design justice, racial justice. I think that people still want to be recognized—as everybody else—as a brilliant designer. Full stop.

SY: As a fullness of their humanity, right?

TSC: Exactly. Exactly.

SY: Fear of ghettoization is what your Asian colleagues shared with me, which is that we want to work on our cultures, but we want to work it in a way that makes it part of the mainstream canonical discourse as opposed to onlyfor the experts in that area because that then becomes a defeatist project—for me. It’s not the case for everyone, but for me, it is a defeating project. Other people are doing fantastic work in that, but these are my own angst and my own—(laughs)

TSC: What do you mean by “defeatist project”?

SY: My fear is that—look, Tonia—I teach in a school of architecture. If I work on South Asia, the students will not be able to come to me and see me as somebody who can help them on doing something in Seattle or solving a housing problem here, or an LGBTQ problem in Utah or in Colorado or something like that, or the contemporariness. So I want to be able to come across to them as somebody who can speak to their concerns because that is my number-one constituency with whom I have on a daily basis a discourse—not only the discourse in writing. So that is what I feel that if my colleagues who—a lot of them who are in the art history departments—they have a bit more freedom because there’s a French scholar, there’s an eighteenth-century-Caribbean scholar, there’s this, that. So the whole department is like that. So the world is a collage—scholarship is a collage of all these things. That’s not the case in architecture schools. Architecture schools are very present minded and very now minded and very naval gazing. So it is about the particular locality, and that is partly the nature of how architecture as a discipline has evolved here where I’m teaching. So that is my fear.

TSC: Hmm. Yeah. Something else I wanted to ask you about is that you said you were talking about taking apart tools and reworking them. Can you give me an example of one?

“My book has been very well reviewed, but almost every book review dealt with the fact that I am an American scholar of South Asian descent, which is not what happens when necessarily somebody works on China who is an American scholar; they just call it American scholarship. But I find it actually a very good thing that it is the model that everybody should approach right now—that we have to place our politics, identities, and research methods on the table.”

Interview Segment: Identities on the table

SY: So I’ll give you a good example of

something that I’m working on right now, which is the category of noise. So

noise in—most of the scholarship in the United States and Europe has been

geared towards quietening the cities. After the invention of mechanical power

and electrical power, it has all been about kind of privacy, silencing, because

we see the individual and even the family as a kind of coming together of

individuals. Whereas in

South Asia where I’m working, the sense of self—and place, and sounds, and

noise—is knowledge. Noise is full of agentic energies, especially in South

Asian cities. It is the number-one tool through which subaltern classes

make space. So I feel that all the discourse that I have gathered on sound, and

resonance, and theaters, and ethereality, and Le Corbusier’s kind of like—it is

all about crafting sound for these exquisite experiences rather than the

deafening sounds of South Asian shrines that I am studying, which are where the

noise creates new types of privacies within public space.

So the traditional categories of rational and emotive spaces of private and public spaces, of self and the other, of privacy and publicity, of space of appearance and space of privacy—none of those categories work. It took me five or seven years to recognize noise as a highly rich medium for studying spaces and studying how space is produced and how actually there’s a lot of knowledge production in noise. So because we usually associate sound and silence with thinking, right? And I’m working in one of the quietest libraries in the world writing about noise and cacophony and energies within these things. So I have until very recently been trying to find beautiful resonance spaces like Hagia Sophia that don’t exist in South Asia!

They are all kind of muddled, messy, this, that. And suddenly, a very different type of montage-collaged spaces appear in which architecture operates very differently than creating different acoustical communities. So cacophony is a very radically different type of production of self-relationship to landscape and space, as opposed to Alain Corbin, who’s looking at eighteenth-century church bells in France or nineteenth-century church bells in France—how it creates these beautiful auditory communities. I try to do that with Adhan and the call for prayers, but hazzan has suddenly transformed public space into more of a gendered and masculine space, because unlike church bells, Adhan is a masculine voice.

And there are all these subliminal messages that women’s body kind of just internalize, yet they re-channel these into producing feminist spaces, feminist networks, feminist alliances and roots. I would say that just because I’m working on sound, how it is studied in the West is studied mostly as beautiful moments. People have studied noise as well recently, but to articulate that—so that is a toolbox that I had to unmake with the analytical categories looking at how a dome has been produced and how it takes in and how using softwares to kind of imagine how it would have sounded in the eighteenth century. I’m reproducing all those tools.

TSC: Wow. That’s so fascinating! You’re making me think about so many things related to the connotations we attach to noise versus sound.

I want to talk a little bit more in depth about solidarity. You had mentioned that you wanted students to be able to come to you with any of their questions regardless of what they’re working on and that you didn’t want to be kind of pigeonholed as a South Asian scholar. Do you have South Asian students—

SY: Naren. (laughs)

TSC: I know, yes, Naren. (laughs) But do you have South Asian students coming to you seeking out mentorship specifically because you are also South Asian? Have they expressed that to you?

SY: So I have been approached by a lot of students who—because I teach Gen Ed. courses, a lot of students who may or may not be in architecture who come to me and feel kind of an affinity with me, but also feel that I can provide them something that their parents cannot provide them because I’m a professor, so I have certain authority. But I am also somebody who wears my gender identity, my gender politics, as well as—I literally go into my classroom and present myself as a feminist Muslim and then make fun of it—that it might come across as an oxymoronic, right? I make fun of my accent. It attracts a lot of South Asian students—two types: One who have just come fresh off the boat, and they have no friends, no peers, so they come to me. They’re the disoriented students. I actually help them, set them up—kind of a lot of work with them.

Another type of students who come to me who are South Asian and who come to me and talk to me that they want to have a coffee or this or that because they don’t necessarily need a mentor or they don’t know what to do with the idea of a mentor. There are students who have either come at a very young age or have grown up here entirely, like my daughter or like yourself. You were born in the US, right?

TSC: Yeah.

So the traditional categories of rational and emotive spaces of private and public spaces, of self and the other, of privacy and publicity, of space of appearance and space of privacy—none of those categories work. It took me five or seven years to recognize noise as a highly rich medium for studying spaces and studying how space is produced and how actually there’s a lot of knowledge production in noise. So because we usually associate sound and silence with thinking, right? And I’m working in one of the quietest libraries in the world writing about noise and cacophony and energies within these things. So I have until very recently been trying to find beautiful resonance spaces like Hagia Sophia that don’t exist in South Asia!

They are all kind of muddled, messy, this, that. And suddenly, a very different type of montage-collaged spaces appear in which architecture operates very differently than creating different acoustical communities. So cacophony is a very radically different type of production of self-relationship to landscape and space, as opposed to Alain Corbin, who’s looking at eighteenth-century church bells in France or nineteenth-century church bells in France—how it creates these beautiful auditory communities. I try to do that with Adhan and the call for prayers, but hazzan has suddenly transformed public space into more of a gendered and masculine space, because unlike church bells, Adhan is a masculine voice.

And there are all these subliminal messages that women’s body kind of just internalize, yet they re-channel these into producing feminist spaces, feminist networks, feminist alliances and roots. I would say that just because I’m working on sound, how it is studied in the West is studied mostly as beautiful moments. People have studied noise as well recently, but to articulate that—so that is a toolbox that I had to unmake with the analytical categories looking at how a dome has been produced and how it takes in and how using softwares to kind of imagine how it would have sounded in the eighteenth century. I’m reproducing all those tools.

TSC: Wow. That’s so fascinating! You’re making me think about so many things related to the connotations we attach to noise versus sound.

I want to talk a little bit more in depth about solidarity. You had mentioned that you wanted students to be able to come to you with any of their questions regardless of what they’re working on and that you didn’t want to be kind of pigeonholed as a South Asian scholar. Do you have South Asian students—

SY: Naren. (laughs)

TSC: I know, yes, Naren. (laughs) But do you have South Asian students coming to you seeking out mentorship specifically because you are also South Asian? Have they expressed that to you?

SY: So I have been approached by a lot of students who—because I teach Gen Ed. courses, a lot of students who may or may not be in architecture who come to me and feel kind of an affinity with me, but also feel that I can provide them something that their parents cannot provide them because I’m a professor, so I have certain authority. But I am also somebody who wears my gender identity, my gender politics, as well as—I literally go into my classroom and present myself as a feminist Muslim and then make fun of it—that it might come across as an oxymoronic, right? I make fun of my accent. It attracts a lot of South Asian students—two types: One who have just come fresh off the boat, and they have no friends, no peers, so they come to me. They’re the disoriented students. I actually help them, set them up—kind of a lot of work with them.

Another type of students who come to me who are South Asian and who come to me and talk to me that they want to have a coffee or this or that because they don’t necessarily need a mentor or they don’t know what to do with the idea of a mentor. There are students who have either come at a very young age or have grown up here entirely, like my daughter or like yourself. You were born in the US, right?

TSC: Yeah.

“Whereas in South Asia where I’m working, the sense of self—and place, and sounds, and noise—is knowledge. Noise is full of agentic energies, especially in South Asian cities.”

SY: All right. So they’re like you who have this inarticulate hunger inside

of them for an anchor. They want to move away from their parents because the

parents have given them what they’ve given them, and they are at that age where

they’ve outgrown them, but they still need adults. They still need anchors, but they need anchors who

will help them grow up rather than remain infantile, which is what I feel that—sorry

to say, (laughs) but South Asian parents in particular do, especially those who

are afraid of the threats of diaspora. So those are the students that I

attract.

Somehow, I also attract a lot of LGBTQ students who are white and Mormons. I have no idea why. I also attract a lot of Jack Mormons: kids who have left the church but also want to keep a relationship with their parents, who want to navigate that world because I think that they see me as somebody who gives them a language for thinking about religion in a cultural way and religion as a source of power rather than a source of false consciousness and all that.

TSC: Yeah. I think, in some parts of the states and probably in Utah, anybody who is seen as not cis, straight, white, male, Mormon—people with marginalized identities will feel a sense of affinity to. So that’s probably why.

SY: That whole community, when they see me and when they’re in need of somebody older, they come to me for one reason or another. So I write a lot of grants for them. I find them fellowships; I find them jobs. I give them kind of career advice, things like that—students who are having difficulty with their parents. I’m sure that they go to other professors as well. But I think that I offer somebody who is very situated in the world in a very legitimate way because I am within the mainstream of society. At the same time, I’m somebody who constantly signals openness to them in a way that I feel that professors in East Coast or West Coast do not do because they are far more rigid in their liberalism, and they’re far more myopic. So they are not able to meet these students halfway because they reject all of the cultural heritage or the environments in which they’ve grown up as they dismiss them, right? And I don’t dismiss them. I see them as sources of producing one type of reality.

TSC: Yeah. You said a phrase, "the threats of diaspora." Can you expand on that?

SY: So this is something that I feel a lot in my cousins and my family members and a lot of South Asian community that is not in the universities. So I don’t feel this about any of the South Asian professors or intellectuals, but I do see it in a lot of the doctors, a lot of the bourgeoisie classes, of kind of mechanical engineers and civil engineers afraid that their kids would either end up—God forbid—in humanities, which is like the biggest tragedy, or in the arts, right?

And they’re really, really afraid that the kids would lose their language. So then they think that they would have not passed on that, right? The world outside the house is much greater. So I know that a lot of people in Boston—I don’t have a big South Asian community in Salt Lake, but I lived in Boston for twelve to fifteen years. And in that community, there are different types of people who have different levels of fear of influence from the outside.

So the biggest tragedy is if their kid decides to marry outside of the Pakistani diasporic community, or having sex outside of marriage, or having a lot of white friends. If they just marry South Asian, or marry Muslim, or marry Hindu, depending on what their religious background is, then all is well. So a lot hinges on the pressure that they put on their partners. So that is the fear of influence. You’ve come here, but there is this gap that you want the US to be there for all the freedoms and economic opportunities, but you do not want to partake in its cultural values that do not work for you.

I don’t know whether that’s the experience that you have with your parents, but that’s the experience that I have noticed a lot of my Pakistani community imposing on their kids. They have these big parties where only Pakistanis meet Pakistani. They all dress up in Pakistani clothes. They only eat Pakistani food, so the houses stink of Pakistani stuff. The kids, if they fit into it, fantastic. If they don’t fit into it, then they’ll revolt against it, right? So they don’t bring friends home because the house smells of cumin. They don’t socialize with their friends and cousins. A lot of them kind of modernize, which is—so they’ll do rap in Urdu with Pakistan—their diasporic issues. And that their parents are very open to. That, they’re very open to, as long as they have nine-to-five jobs and they have—

TSC: A Pakistani partner.

SY: A Pakistani partner, and they are standing on their own two feet financially—then there are a lot of openness.

TSC: Yeah. I think we’re a half generation apart, but it’s still interesting hearing your perspective of the other side of that pressure. But you don’t impose these things on your daughter. At least, that is not how I perceive it. You just are witnessing it in people around you in your community.

SY: Yeah.

TSC: So I want to talk a little bit about Nááts’íilid Initiative, because we met through various precursor activities that led to the formation of the nonprofit. How and why did you get involved with Nááts’íilid Initiative?

SY: Okay. So, at a very mundane level, I got involved in Nááts’íilid Initiative because of an article that I had co-written with José in Dialecticas a critique of DesignBuildBLUFF and some of the hiring practices at our school, and the lack of understanding of the ongoing colonial nature of architectural education, both at Bluff and at the University of Utah. And the lack of understanding or appreciation of that by my very sophisticated, brilliant, thoughtful colleagues.

So that was an article that I wrote, but what happened at the end of the article, I found that there was a limit to scholarship. Scholarship can only do so much. I felt that scholarship cannot do the work of reparations in a way because the readers for this type of work are not—I’m not giving them any tools for how to respond to it. And I don’t have those tools either.

So I became interested when I got invited by José and Nathaniel Brown and Renee into the community. I became very, very interested in this as a possibility of testing out many of the things that I have explored in scholarship but not translated those values and those ideas into practice which required very many different skills. The grant writing that you do for scholarship and the grant writing that you do for doing design projects in the community is radically different. The kind of alliances and the kinds of speech you need to do both at the university level and the community level and at the nonprofit community level is radically different, for which I have no preparation, no training, and no exposure. And so Nááts’íilid became kind of jump first, think later because we all have one life. We can’t just wait and wait on getting it right. So learning by doing was what brought me to Nááts’íilid.

I also felt that the invisibility of Indigenous knowledge in Utah, as well as my own knowledge of it, was so great that I could not tell students how to do post-colonial practice if I don’t know other Indigenous and local ways of making, and all I know are either European or South Asian ways of making. Criticism has to lead to some kind of action, and nobody else is going to do it. I have to do this myself and I have to develop new types of skills. And I thought if I’m going to train my students to become activist architects, then I have to figure out what are the skills that they require.

So all the work of Nááts’íilid is actually Janus-faced. It faces one side the community, and the other side, the university. So what I learned from the university, I bring to the community and weave into what they’re teaching me, and what they’re teaching me, I hope to take back to my students. So it has to be this double face. So I thought Nááts’íilid was going to solve a problem for me or give me experience and training that I had to take responsibility for.

TSC: Did you feel any specificity towards Navajo and Indigenous communities, and was it because you were at Utah and DesignBuildBLUFFwas there?

SY: One, we are sitting on their ground. So we cannot be only doing a performing kind of land acknowledgements. You have to make the land acknowledgement be embodied in your work. So that was one. But the other thing was also that I had done a project called Archipedia Utah, in which I became really familiar with the breadth and the depth and the complexity of the historical architectural production over here, and I became very excited about all that I had learned, but I also felt completely, completely blind about the Navajo contemporary design practices. I think that that is what made—but also not only DesignBuildBLUFF, because they invited me. It is in my neighborhood. I have written about it. We have a school in there. So there were all these confluence of concerns.

But also, Tonia, there are eight different tribes in Utah, and I met with each one of them before we established Nááts’íilid. I met with the representatives, and actually, Francie Taylor organized for me and Lisa Henry Benham, who was at that time the associate chair of the department. She set up meetings for us to meet with the representatives from all the eight tribes and we realized that none of them had the capacity—the capacity—to get help from us. So they can’t make meetings; they can’t design a design problem because they are always in kind of emergency mode. Whereas Navajo being large enough, being a bit more organized with all the problems in the world that it has, had the capacity to invite us and kind of design projects that they wanted us to pursue.

TSC: Yeah. That makes sense. You talk a lot about being invited into this space. I know that we as Nááts’íilid and also you have experienced some resistance to our role or presence in this work, even as we see it as racial justice and solidarity work. Can you reflect a little bit on some of those experiences—whether they’re with Nááts’íilid or other projects that you’ve worked on? What was the experience like? What did you learn from it? What do you think we can learn from it as a community of Asian or South Asian or other non-Indigenous communities working in solidarity with Indigenous groups?

SY: I always felt until very recently that the work would move forward mainly if we did work in trust building with the community. But I have now kind of come to realize that there is such a lack of trust inter-community—between themselves. And there is such trauma and animosity towards any kind of innovative work. I’ve had a lot of challenges recently on some of the Department of Energy projects that we are working on especially because the government has changed, and the transfer of information and power is not geared towards kind of sustaining the relationships that one builds. So when one set of people lose power and another set of people come into power, it can go in either direction.

So the problem is that means that the institutions are still very personalized, and the institutions are persons, and the systems are embodied within people and not yet in processes that are in place. So the processes are not nimble. They are very, very bureaucratic, which is the case everywhere. So it makes working in the community as outsiders, as people of color, very, very difficult because new people see us as just people who are there to exploit them. They don’t want to talk to us; they don’t want to work with us; and we have to do a lot of work. So there is a lot of anxiety of being exploited. And plus, the community is—people like you and I who are doing this embedded work in the community, the question of embeddedness is a very difficult one because we live very far away. Even though mentally we are in this community 24/7, we physically live very far away from them.

That is where the question of technology and all these things just doesn’t do the work for us—hasn’t done the work for us yet. So I feel that it’s two steps forward and three steps back all the time, or sometimes it is two steps forward and one step back. Sometimes it is two steps forward and it remains two steps forward, right? So there are all these different conditions in which we recede. We make a lot of effort, and we move an inch. But I would say that the only option, Tonia, that we do not have—we do not have a choice of giving up. We just cannot give up no matter how much we are pushed, pulled, distrusted, whatever. That’s not an option.

Somehow, I also attract a lot of LGBTQ students who are white and Mormons. I have no idea why. I also attract a lot of Jack Mormons: kids who have left the church but also want to keep a relationship with their parents, who want to navigate that world because I think that they see me as somebody who gives them a language for thinking about religion in a cultural way and religion as a source of power rather than a source of false consciousness and all that.

TSC: Yeah. I think, in some parts of the states and probably in Utah, anybody who is seen as not cis, straight, white, male, Mormon—people with marginalized identities will feel a sense of affinity to. So that’s probably why.

SY: That whole community, when they see me and when they’re in need of somebody older, they come to me for one reason or another. So I write a lot of grants for them. I find them fellowships; I find them jobs. I give them kind of career advice, things like that—students who are having difficulty with their parents. I’m sure that they go to other professors as well. But I think that I offer somebody who is very situated in the world in a very legitimate way because I am within the mainstream of society. At the same time, I’m somebody who constantly signals openness to them in a way that I feel that professors in East Coast or West Coast do not do because they are far more rigid in their liberalism, and they’re far more myopic. So they are not able to meet these students halfway because they reject all of the cultural heritage or the environments in which they’ve grown up as they dismiss them, right? And I don’t dismiss them. I see them as sources of producing one type of reality.

TSC: Yeah. You said a phrase, "the threats of diaspora." Can you expand on that?

SY: So this is something that I feel a lot in my cousins and my family members and a lot of South Asian community that is not in the universities. So I don’t feel this about any of the South Asian professors or intellectuals, but I do see it in a lot of the doctors, a lot of the bourgeoisie classes, of kind of mechanical engineers and civil engineers afraid that their kids would either end up—God forbid—in humanities, which is like the biggest tragedy, or in the arts, right?

And they’re really, really afraid that the kids would lose their language. So then they think that they would have not passed on that, right? The world outside the house is much greater. So I know that a lot of people in Boston—I don’t have a big South Asian community in Salt Lake, but I lived in Boston for twelve to fifteen years. And in that community, there are different types of people who have different levels of fear of influence from the outside.

So the biggest tragedy is if their kid decides to marry outside of the Pakistani diasporic community, or having sex outside of marriage, or having a lot of white friends. If they just marry South Asian, or marry Muslim, or marry Hindu, depending on what their religious background is, then all is well. So a lot hinges on the pressure that they put on their partners. So that is the fear of influence. You’ve come here, but there is this gap that you want the US to be there for all the freedoms and economic opportunities, but you do not want to partake in its cultural values that do not work for you.

I don’t know whether that’s the experience that you have with your parents, but that’s the experience that I have noticed a lot of my Pakistani community imposing on their kids. They have these big parties where only Pakistanis meet Pakistani. They all dress up in Pakistani clothes. They only eat Pakistani food, so the houses stink of Pakistani stuff. The kids, if they fit into it, fantastic. If they don’t fit into it, then they’ll revolt against it, right? So they don’t bring friends home because the house smells of cumin. They don’t socialize with their friends and cousins. A lot of them kind of modernize, which is—so they’ll do rap in Urdu with Pakistan—their diasporic issues. And that their parents are very open to. That, they’re very open to, as long as they have nine-to-five jobs and they have—

TSC: A Pakistani partner.

SY: A Pakistani partner, and they are standing on their own two feet financially—then there are a lot of openness.

TSC: Yeah. I think we’re a half generation apart, but it’s still interesting hearing your perspective of the other side of that pressure. But you don’t impose these things on your daughter. At least, that is not how I perceive it. You just are witnessing it in people around you in your community.

SY: Yeah.

TSC: So I want to talk a little bit about Nááts’íilid Initiative, because we met through various precursor activities that led to the formation of the nonprofit. How and why did you get involved with Nááts’íilid Initiative?

SY: Okay. So, at a very mundane level, I got involved in Nááts’íilid Initiative because of an article that I had co-written with José in Dialecticas a critique of DesignBuildBLUFF and some of the hiring practices at our school, and the lack of understanding of the ongoing colonial nature of architectural education, both at Bluff and at the University of Utah. And the lack of understanding or appreciation of that by my very sophisticated, brilliant, thoughtful colleagues.

So that was an article that I wrote, but what happened at the end of the article, I found that there was a limit to scholarship. Scholarship can only do so much. I felt that scholarship cannot do the work of reparations in a way because the readers for this type of work are not—I’m not giving them any tools for how to respond to it. And I don’t have those tools either.

So I became interested when I got invited by José and Nathaniel Brown and Renee into the community. I became very, very interested in this as a possibility of testing out many of the things that I have explored in scholarship but not translated those values and those ideas into practice which required very many different skills. The grant writing that you do for scholarship and the grant writing that you do for doing design projects in the community is radically different. The kind of alliances and the kinds of speech you need to do both at the university level and the community level and at the nonprofit community level is radically different, for which I have no preparation, no training, and no exposure. And so Nááts’íilid became kind of jump first, think later because we all have one life. We can’t just wait and wait on getting it right. So learning by doing was what brought me to Nááts’íilid.

I also felt that the invisibility of Indigenous knowledge in Utah, as well as my own knowledge of it, was so great that I could not tell students how to do post-colonial practice if I don’t know other Indigenous and local ways of making, and all I know are either European or South Asian ways of making. Criticism has to lead to some kind of action, and nobody else is going to do it. I have to do this myself and I have to develop new types of skills. And I thought if I’m going to train my students to become activist architects, then I have to figure out what are the skills that they require.

So all the work of Nááts’íilid is actually Janus-faced. It faces one side the community, and the other side, the university. So what I learned from the university, I bring to the community and weave into what they’re teaching me, and what they’re teaching me, I hope to take back to my students. So it has to be this double face. So I thought Nááts’íilid was going to solve a problem for me or give me experience and training that I had to take responsibility for.

TSC: Did you feel any specificity towards Navajo and Indigenous communities, and was it because you were at Utah and DesignBuildBLUFFwas there?

SY: One, we are sitting on their ground. So we cannot be only doing a performing kind of land acknowledgements. You have to make the land acknowledgement be embodied in your work. So that was one. But the other thing was also that I had done a project called Archipedia Utah, in which I became really familiar with the breadth and the depth and the complexity of the historical architectural production over here, and I became very excited about all that I had learned, but I also felt completely, completely blind about the Navajo contemporary design practices. I think that that is what made—but also not only DesignBuildBLUFF, because they invited me. It is in my neighborhood. I have written about it. We have a school in there. So there were all these confluence of concerns.

But also, Tonia, there are eight different tribes in Utah, and I met with each one of them before we established Nááts’íilid. I met with the representatives, and actually, Francie Taylor organized for me and Lisa Henry Benham, who was at that time the associate chair of the department. She set up meetings for us to meet with the representatives from all the eight tribes and we realized that none of them had the capacity—the capacity—to get help from us. So they can’t make meetings; they can’t design a design problem because they are always in kind of emergency mode. Whereas Navajo being large enough, being a bit more organized with all the problems in the world that it has, had the capacity to invite us and kind of design projects that they wanted us to pursue.

TSC: Yeah. That makes sense. You talk a lot about being invited into this space. I know that we as Nááts’íilid and also you have experienced some resistance to our role or presence in this work, even as we see it as racial justice and solidarity work. Can you reflect a little bit on some of those experiences—whether they’re with Nááts’íilid or other projects that you’ve worked on? What was the experience like? What did you learn from it? What do you think we can learn from it as a community of Asian or South Asian or other non-Indigenous communities working in solidarity with Indigenous groups?

SY: I always felt until very recently that the work would move forward mainly if we did work in trust building with the community. But I have now kind of come to realize that there is such a lack of trust inter-community—between themselves. And there is such trauma and animosity towards any kind of innovative work. I’ve had a lot of challenges recently on some of the Department of Energy projects that we are working on especially because the government has changed, and the transfer of information and power is not geared towards kind of sustaining the relationships that one builds. So when one set of people lose power and another set of people come into power, it can go in either direction.

So the problem is that means that the institutions are still very personalized, and the institutions are persons, and the systems are embodied within people and not yet in processes that are in place. So the processes are not nimble. They are very, very bureaucratic, which is the case everywhere. So it makes working in the community as outsiders, as people of color, very, very difficult because new people see us as just people who are there to exploit them. They don’t want to talk to us; they don’t want to work with us; and we have to do a lot of work. So there is a lot of anxiety of being exploited. And plus, the community is—people like you and I who are doing this embedded work in the community, the question of embeddedness is a very difficult one because we live very far away. Even though mentally we are in this community 24/7, we physically live very far away from them.

That is where the question of technology and all these things just doesn’t do the work for us—hasn’t done the work for us yet. So I feel that it’s two steps forward and three steps back all the time, or sometimes it is two steps forward and one step back. Sometimes it is two steps forward and it remains two steps forward, right? So there are all these different conditions in which we recede. We make a lot of effort, and we move an inch. But I would say that the only option, Tonia, that we do not have—we do not have a choice of giving up. We just cannot give up no matter how much we are pushed, pulled, distrusted, whatever. That’s not an option.

“They still need anchors, but they need anchors who will help them grow up rather than remain infantile, which is what I feel that—sorry to say, (laughs) but South Asian parents in particular do, especially those who are afraid of the threats of diaspora. So those are the students that I attract. ”

We have to realize that this has

to be our life’s strife, and we cannot jump from community to community,

project to project. We have to teach our students—I have to teach my students

to create roots in a place. And that is one of the biggest challenges of

diasporic communities, whether it is people who are white or non-white. We all

have that challenge of kind of feeling alienated. We can’t go back to China and

Pakistan. We can’t go back to Taiwan and Hong Kong. We are here. This is our

home. So the most important thing is that we have to create roots, and we have

to create a sense of belonging here, right? But we will always remain in

multiple pluralities. We will always be at once global and local players, and

we should see strength in that rather than weakness. We should see an

expansiveness in that rather than that it compromises us. I don’t know how one

can do that, except that just remain steadfast and have integrity, right? Those

are your only cash crops. (laughs) Everything else can go up and down. This is

the only thing that you can control: your integrity and your resolve.

TSC: Just keep taking steps forward. (laughs)

In thinking about your daughter, and maybe some of your South Asian design students that you’ve mentored, what are your hopes or dreams for South Asian diasporic communities and spaces and people who are shaping them through design?

SY: Very simply, to actually bring traditional folk modern classical systems that have developed in those communities and how you understand them, recognize yourself as a filter and bring them into the knowledge system with which you’re working. So, for example, my daughter knows little about if she’s planning to become a sociologist. Naren is a good example, who’s becoming an architect and I am kind of teaching him skills—how to recognize intelligence in poverty. Architecture of scarcity, resilience in slums architecture. Not only look at high art, not only look at low art, but to see that there’s knowledge and intelligence in all levels of all societies in vernacular, in gendered spaces, whatever.

And rather than to do this kind of normative liberal Western critique of them as a break with the past or continuity with tradition or whatever, we should actually be the ambassadors for integrating the knowledge that you embody, the knowledge that you gather from here, the knowledge that you bring with you from the worlds from where you come. For those who don’t come from other worlds but have grown up here like yourself, or like my daughter, I would say to theorize the knowledge that is coming out of the diaspora over here and to recognize that as a full and valuable knowledge system in its own in which there is no similar kind of body-mind divide.

TSC: Just keep taking steps forward. (laughs)

In thinking about your daughter, and maybe some of your South Asian design students that you’ve mentored, what are your hopes or dreams for South Asian diasporic communities and spaces and people who are shaping them through design?

SY: Very simply, to actually bring traditional folk modern classical systems that have developed in those communities and how you understand them, recognize yourself as a filter and bring them into the knowledge system with which you’re working. So, for example, my daughter knows little about if she’s planning to become a sociologist. Naren is a good example, who’s becoming an architect and I am kind of teaching him skills—how to recognize intelligence in poverty. Architecture of scarcity, resilience in slums architecture. Not only look at high art, not only look at low art, but to see that there’s knowledge and intelligence in all levels of all societies in vernacular, in gendered spaces, whatever.