“I understand the importance of me doing things publicly. It’s still significant that people know what my work is and what I look like.”

she/her

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I’m here with Sophie Weston Chien for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora.

To start out, I would love it if you would tell me about how your identity as Chinese and as mixed race has played a role in your experience growing up. What was your family home like? Did you grow up around other Chinese mixed or immigrant families?

Sophie Weston Chien (SWC): I don’t know. I mean, so many things! (laughs) So I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina. But my parents are not from there. They’re from a lot of different places, but definitely not from the South. So I think it was like a kind of doubly displaced, confusing place to be. My dad is—and this is something that I’m actually still grappling with—but my dad is Chinese-Brazilian—I think is accurate to say. He was born off the coast of Brazil when his parents were leaving China in 1960. So a very specific time and place to be. He grew up in Brazil for thirteen years and then moved to Queens—well, maybe Manhattan and then to Queens, but New York City. My mom moved around a few times, but she basically grew up in upstate New York; she’s white. My parents met the first day of architecture school, actually.

So I kind of grew up, I think in some ways—and maybe this is jumping the gun—but, in some ways, the only language that felt like we all shared as a family was design, actually. Growing up in Charlotte, there were just no Chinese people around me ever. My parents moved to the South to be closer to my mom’s parents. So there was no community there waiting for them. I think my dad, for a number of reasons, kind of because of his trauma, didn’t reach out to try to find a community—a Chinese community while he was there. So I really didn’t grow up around any Chinese people besides my immediate family.

There’s a kind of stark reminder of that when—I think my mom in good faith tried to—and it wasn’t spoken in the house either—my mom in good faith, I think, tried to teach us Chinese and enroll us in Chinese school. But it was the same time as Sunday school. Everyone else in the class had two Chinese speakers at home so they were progressing really quickly, had already learned stuff, and were basically learning how to write. So me and my brother had such a hard time that she let us decide between Sunday school and Chinese school, and we chose Sunday school. (laughs) So I don’t speak any Chinese at all which is super sad—or Portuguese, which I think are both my dad’s native tongues. That’s another point of alienation for me.

TSC: It’s interesting that it was your mom who made the effort to try to teach you Chinese almost on behalf of your dad’s side of the family.

SWC: I think there could be a whole novel written about my parents’ understanding, or even just race through my mom’s eyes has been really interesting. She didn’t understand that I was racialized until like three or four years ago—is what she told me, which I was like—is wild! Growing up, I would be out with her—it’d just be the two of us and people would ask me if I was adopted, which is just an incredibly uncool thing to ask a child when they’re with a caretaker. It doesn’t matter; don’t ask that!

TSC: Wouldn’t be an appropriate question to ask a stranger!

SWC: It’s like, “What?” So in so many ways, I think because my last name was Chinese, I couldn’t pass as anything else when people knew my name. But honestly, growing up in Charlotte, most people thought I was Mexican American just because that was the kind of racialized population that I looked like the most in the area. So people had no idea. I guess just, like, being mixed race too, I’ve had a lot of conversations with people and it’s just like, when you don’t look like either of your parents, it’s a really specific experience. I looked like my brother so that was like, “Okay, we’re from the same place at least.” But yeah, that was also, I think, part of it too.

TSC: Thank you for sharing that. I’m curious—Chinese school didn’t quite work out—but were there spaces when you were growing up where you felt like you found community or where you felt like you saw yourself or your experience reflected from a race or ethnicity perspective?

SWC: Yeah, so I went to a magnet elementary school. I have two BIPOC friends from elementary school who I’m still friends with now. One of them is Canadian Iranian American. The other one is actually the same mix as me except Vietnamese and not Chinese. So she has a Vietnamese dad and a white mom also named Karin. Her parents also met in college—med school. So I think it’s like a really specific kind of like—especially for the two of us, understanding, where our mixed race lineage comes from class-wise too, which is another way to think about it. But yeah, I think we all knew, and even later too, we realized we were all first gen. And just like that really, the unspoken-ness of that and the expectations, I think, really bonded us.

I actually didn’t realize until a couple years ago talking to them that their parents, I think, were a lot more stereotypical and demanded they either get a doctorate or an MD—JD, MD or PhD, which I never had that kind of pressure. I think in some ways my parents are pretty atypical. But we definitely had solidarity with each other in terms of getting through these predominantly white spaces and kind of excelling in school. But knowing we had each other at least to talk through things.

TSC: You mentioned that your mom only became aware recently in the past few years that you were racialized as Asian, which is so surprising to me. But I’m curious what your experience of coming into that realization was growing up, especially given that you were raised in a mixed family and that you were surrounded by mostly white people in your communities?

SWC: I mean, I knew immediately. I think I became so self-aware because of my race growing up, which is funny because my brother wasn’t. But I think that’s also how gender plays into things. But I knew immediately. I think it also—in terms of solidarity and understanding community-building work, I think it really pushed me to be a community builder because there was no natural place for me to be. So I always felt like I had to build a community around me because there was no obvious fit for where I should go. I do think that was pretty important.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I’m here with Sophie Weston Chien for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora.

To start out, I would love it if you would tell me about how your identity as Chinese and as mixed race has played a role in your experience growing up. What was your family home like? Did you grow up around other Chinese mixed or immigrant families?

Sophie Weston Chien (SWC): I don’t know. I mean, so many things! (laughs) So I grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina. But my parents are not from there. They’re from a lot of different places, but definitely not from the South. So I think it was like a kind of doubly displaced, confusing place to be. My dad is—and this is something that I’m actually still grappling with—but my dad is Chinese-Brazilian—I think is accurate to say. He was born off the coast of Brazil when his parents were leaving China in 1960. So a very specific time and place to be. He grew up in Brazil for thirteen years and then moved to Queens—well, maybe Manhattan and then to Queens, but New York City. My mom moved around a few times, but she basically grew up in upstate New York; she’s white. My parents met the first day of architecture school, actually.

So I kind of grew up, I think in some ways—and maybe this is jumping the gun—but, in some ways, the only language that felt like we all shared as a family was design, actually. Growing up in Charlotte, there were just no Chinese people around me ever. My parents moved to the South to be closer to my mom’s parents. So there was no community there waiting for them. I think my dad, for a number of reasons, kind of because of his trauma, didn’t reach out to try to find a community—a Chinese community while he was there. So I really didn’t grow up around any Chinese people besides my immediate family.

There’s a kind of stark reminder of that when—I think my mom in good faith tried to—and it wasn’t spoken in the house either—my mom in good faith, I think, tried to teach us Chinese and enroll us in Chinese school. But it was the same time as Sunday school. Everyone else in the class had two Chinese speakers at home so they were progressing really quickly, had already learned stuff, and were basically learning how to write. So me and my brother had such a hard time that she let us decide between Sunday school and Chinese school, and we chose Sunday school. (laughs) So I don’t speak any Chinese at all which is super sad—or Portuguese, which I think are both my dad’s native tongues. That’s another point of alienation for me.

TSC: It’s interesting that it was your mom who made the effort to try to teach you Chinese almost on behalf of your dad’s side of the family.

SWC: I think there could be a whole novel written about my parents’ understanding, or even just race through my mom’s eyes has been really interesting. She didn’t understand that I was racialized until like three or four years ago—is what she told me, which I was like—is wild! Growing up, I would be out with her—it’d just be the two of us and people would ask me if I was adopted, which is just an incredibly uncool thing to ask a child when they’re with a caretaker. It doesn’t matter; don’t ask that!

TSC: Wouldn’t be an appropriate question to ask a stranger!

SWC: It’s like, “What?” So in so many ways, I think because my last name was Chinese, I couldn’t pass as anything else when people knew my name. But honestly, growing up in Charlotte, most people thought I was Mexican American just because that was the kind of racialized population that I looked like the most in the area. So people had no idea. I guess just, like, being mixed race too, I’ve had a lot of conversations with people and it’s just like, when you don’t look like either of your parents, it’s a really specific experience. I looked like my brother so that was like, “Okay, we’re from the same place at least.” But yeah, that was also, I think, part of it too.

TSC: Thank you for sharing that. I’m curious—Chinese school didn’t quite work out—but were there spaces when you were growing up where you felt like you found community or where you felt like you saw yourself or your experience reflected from a race or ethnicity perspective?

SWC: Yeah, so I went to a magnet elementary school. I have two BIPOC friends from elementary school who I’m still friends with now. One of them is Canadian Iranian American. The other one is actually the same mix as me except Vietnamese and not Chinese. So she has a Vietnamese dad and a white mom also named Karin. Her parents also met in college—med school. So I think it’s like a really specific kind of like—especially for the two of us, understanding, where our mixed race lineage comes from class-wise too, which is another way to think about it. But yeah, I think we all knew, and even later too, we realized we were all first gen. And just like that really, the unspoken-ness of that and the expectations, I think, really bonded us.

I actually didn’t realize until a couple years ago talking to them that their parents, I think, were a lot more stereotypical and demanded they either get a doctorate or an MD—JD, MD or PhD, which I never had that kind of pressure. I think in some ways my parents are pretty atypical. But we definitely had solidarity with each other in terms of getting through these predominantly white spaces and kind of excelling in school. But knowing we had each other at least to talk through things.

TSC: You mentioned that your mom only became aware recently in the past few years that you were racialized as Asian, which is so surprising to me. But I’m curious what your experience of coming into that realization was growing up, especially given that you were raised in a mixed family and that you were surrounded by mostly white people in your communities?

SWC: I mean, I knew immediately. I think I became so self-aware because of my race growing up, which is funny because my brother wasn’t. But I think that’s also how gender plays into things. But I knew immediately. I think it also—in terms of solidarity and understanding community-building work, I think it really pushed me to be a community builder because there was no natural place for me to be. So I always felt like I had to build a community around me because there was no obvious fit for where I should go. I do think that was pretty important.

Interview Segment: Learning about how I came to be

INTERVIEW 13 DETAILS

Narrator:

Sophie Weston Chien, she/her

Interview Date:

July 13, 2023

Keywords:

Themes: Chinese American Identity, Mixed identity, Brazilian identity, chinese school, designer-organizer, hyphenated experience, landscape architecture, architecture, urban planning, coming correct, community engagement, tufting, miseducation, student as site, 2021 Atlanta spa shootings

Places: Charlotte, North Carolina, Chaohu, Hefei, RISD, Harvard GSD, Alaska, Nome, Seward Peninsula

References: Colloqate, Bryan C. Lee Jr., LA Más/Office of:Office, Everything Everywhere All At Once

ABOUT SOPHIE

Ancestral Land:

Chaohu, China

Homeland:

Sugaree and Catawba Land (Charlotte, NC)

Current Land:

Massachusett and Pawtucket Land (Cambridge, MA)

Diaspora Story:

My dad (who is Chinese) was born on a ship from China to Brazil, grew up in Brazil and moved to NYC when he was 13, my mom (who is white) grew up in upstate New York. They met in undergrad and moved to North Carolina after my mom finished grad school, and that's where I was born and raised. When I went to college I chose to move to New England, one big factor being more Asian peers, and have stayed in the area ever since.

Creative Fields:

Landscape Architecture, Urban Planning, Architecture, Design Research

Racial Justice Affiliations:

Design as Protest, Dark Matter U, Seeding Pedagogies, just practice

Favorite Fruit:

mango

Biography:

Sophie Weston Chien is a designer-organizer. She builds community power through social and ecological infrastructure to liberate sites and histories. Her practice focuses on spatial communication and justice, building on her background in architecture, landscape architecture, urban planning, and political organizing. Her work is often collaborative, and she is a member of several multi-racial and liberation-oriented organizations researching anti-racist design methods and education. Sophie is one-half of the collaboration just practice and co-founder of Seeding Pedagogies Collaborative. She is a core organizer of the Design As Protest Collective, active in Dark Matter University, and on the Board of Directors at DesignxRI. Her work has been published in Log, DISC, v1, PLOT, Portals: Pedagogy, Practice, and Architecture’s Future Imaginary (Actar), exhibited at the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Boston Public Library, Harvard, MIT, Yale, RISD, Brown, Mississippi State and she has spoken at numerous universities and public institutions about her practice. She is driven to promote a social and land-based ethic through a greater understanding of spatial conditions inside academia and public imaginaries.

︎

@swchien

︎ sophiewestonchien.com

But I was hyper aware of it probably even before elementary school

because it was also just like there was no media either. There was maybe one or

two. I think Mulan came around, and that was kind of it. I had Mulanand Pocahontas. But really, just no media about it. My dad just doesn’t

talk about his identity ever, and so there was no access to that from

him. His whole family still lives in New York—Flushing—so we saw them a few

times, but we’re not super close.

TSC: Have you ever had a desire to connect to the parts of China that your dad’s family is from? Have you ever been there?

SWC: It was pulling teeth. We went to visit my cousin who lived in Hong Kong and at my insistence, we flew into China for twenty-four hours to go so I could pay my respects to my grandparents’ grave, and then we flew out. So I’ve been to China for twenty-four hours because that’s how long my dad could stand to be there. (laughs)

TSC: Wow.

SWC: My family is from Chaohu, which is in Hefei. So I think we flew in, into Nanjing from Hong Kong. But past that, nothing. I didn’t name it then, but wanting to be closer to Asians and Asian Americans, I think was a big factor in where I went to college. I knew the South was not a good fit for me. I have learned so, so much from all of my friends that I made in college about what it means to be Asian, what it means to be Asian American, and all of the complexities that come with that. So I think that has been absolutely the biggest way that I’ve learned about all of those things.

TSC: Can you share a little bit more about how having that community has helped you get in touch with that part of your identity?

SWC: I didn’t even know what I was missing. I think also because, visiting my Chinese family in New York City, it was New York, so it was such a novelty that, I think actually living with and being friends with people who just grew up where being Chinese wasn’t unusual, especially in the US context, I was like, It didn’t fit in my brain. What? You weren’t tokenized because there was enough of you? I just can’t even imagine. California? What, that exists? I had no idea. So I think it was and is super formative. I would say now probably half my friends are Asian American—my close friends. So it continues to be super important. I think I started out just learning the kind of easy things of sharing food and understanding culture that way. I have not picked up the language. That one is a big mountain to climb. (laughs) But yeah, it was just so helpful. And I think too, going to RISD, everybody was making art about their identity. So it was, like, a really intimate look into how people were perceiving themselves and then processing it through visual culture. So I learned about the visual culture of Asians and Asian Americans that way too, which was really, really amazing.

TSC: That’s really interesting to experience your Asian identity mostly through being racialized growing up since you had very little exposure to your culture and your heritage and your language and then finding community when you got older to help you self-discover or reconnect or maybe even connect for the first time to your cultural identity as an adult.

SWC: Yeah, definitely! I will say it was definitely intimidating because I felt like I came in with no knowledge. I was like, I can claim this kind of? But I am definitely a learner in this situation even though there’s something baked into my DNA or this big sense. But I definitely felt like an imposter and especially, too, because there were a lot of international students who were actually just Chinese residents who came to study in the US. I was like, Okay, well, we are quitedifferent. So Asian Americans—I feel like specifically Chinese and Korean Americans—were the kind of more natural fit for me in terms of peer-to-peer learning and stuff like that.

TSC: What would you say is your relationship with the term Asian? I know you talked a little bit about imposter syndrome, but do you feel like that label or that identity or that racialization or that word is empowering? Do you feel like it’s limiting in any way?

TSC: Have you ever had a desire to connect to the parts of China that your dad’s family is from? Have you ever been there?

SWC: It was pulling teeth. We went to visit my cousin who lived in Hong Kong and at my insistence, we flew into China for twenty-four hours to go so I could pay my respects to my grandparents’ grave, and then we flew out. So I’ve been to China for twenty-four hours because that’s how long my dad could stand to be there. (laughs)

TSC: Wow.

SWC: My family is from Chaohu, which is in Hefei. So I think we flew in, into Nanjing from Hong Kong. But past that, nothing. I didn’t name it then, but wanting to be closer to Asians and Asian Americans, I think was a big factor in where I went to college. I knew the South was not a good fit for me. I have learned so, so much from all of my friends that I made in college about what it means to be Asian, what it means to be Asian American, and all of the complexities that come with that. So I think that has been absolutely the biggest way that I’ve learned about all of those things.

TSC: Can you share a little bit more about how having that community has helped you get in touch with that part of your identity?

SWC: I didn’t even know what I was missing. I think also because, visiting my Chinese family in New York City, it was New York, so it was such a novelty that, I think actually living with and being friends with people who just grew up where being Chinese wasn’t unusual, especially in the US context, I was like, It didn’t fit in my brain. What? You weren’t tokenized because there was enough of you? I just can’t even imagine. California? What, that exists? I had no idea. So I think it was and is super formative. I would say now probably half my friends are Asian American—my close friends. So it continues to be super important. I think I started out just learning the kind of easy things of sharing food and understanding culture that way. I have not picked up the language. That one is a big mountain to climb. (laughs) But yeah, it was just so helpful. And I think too, going to RISD, everybody was making art about their identity. So it was, like, a really intimate look into how people were perceiving themselves and then processing it through visual culture. So I learned about the visual culture of Asians and Asian Americans that way too, which was really, really amazing.

TSC: That’s really interesting to experience your Asian identity mostly through being racialized growing up since you had very little exposure to your culture and your heritage and your language and then finding community when you got older to help you self-discover or reconnect or maybe even connect for the first time to your cultural identity as an adult.

SWC: Yeah, definitely! I will say it was definitely intimidating because I felt like I came in with no knowledge. I was like, I can claim this kind of? But I am definitely a learner in this situation even though there’s something baked into my DNA or this big sense. But I definitely felt like an imposter and especially, too, because there were a lot of international students who were actually just Chinese residents who came to study in the US. I was like, Okay, well, we are quitedifferent. So Asian Americans—I feel like specifically Chinese and Korean Americans—were the kind of more natural fit for me in terms of peer-to-peer learning and stuff like that.

TSC: What would you say is your relationship with the term Asian? I know you talked a little bit about imposter syndrome, but do you feel like that label or that identity or that racialization or that word is empowering? Do you feel like it’s limiting in any way?

“I think it also—in terms of solidarity and understanding community-building work, I think it really pushed me to be a community builder because there was no natural place for me to be.”

SWC:

I mean, I think that Asianis a response to our white supremacist society. It’s only helpful for

non-Asians to say that I’m Asian. It’s not quite the, “I’m non-white,” but it’s

one step more specific than that. So I don’t really find it that empowering

because I think it flattens just the incredible diversity of possibilities.

I want even more specific than Chinese Brazilian American, right?

Because I’m like half first gen, mixed, all of these things. I’m like, I need

like six hyphens. So just one umbrella term feels kind of woefully inadequate.

It’s helpful on the face as, like, a shorthand, but I think as a society we’re

also kind of ready to dig in a little bit more and get more nuanced. So I’m

excited for that.

TSC: I’ve noticed that the younger generation—I sound really old now—embraces difference much more than the generation that I grew up with. There is a desire to get super specific and really celebrate the nuances within the diaspora population here.

I want to talk a little bit about your design work. You said that design was a language that you shared with your family. The way that I see you is that you’ve really forged a unique interdisciplinary but also highly focused path for yourself at a pretty early stage in your career, which is really exciting. I want to hear how you would describe your work and also how your upbringing and your identity has shaped your creative path and the way that you approach your work.

SWC: Well, I have formulated this idea for myself, but I call myself a designer-organizer. My joke is that it’s because I have a hyphenated experience, so I needed another hyphen. But I think also it’s really the acknowledgement that I grew up understanding the capabilities and the limitations of what the built environment can change or not about people’s lives. So I’m not satisfied with that. I wanted from the get-go to have a practice that understood, Okay, these are the actual things that the built environment can influence. How can we organize around those to make them influence more things, better things, and have more power over what actually gets built in the world because it affects so much about how we live and who has access to what.

TSC: I’ve noticed that the younger generation—I sound really old now—embraces difference much more than the generation that I grew up with. There is a desire to get super specific and really celebrate the nuances within the diaspora population here.

I want to talk a little bit about your design work. You said that design was a language that you shared with your family. The way that I see you is that you’ve really forged a unique interdisciplinary but also highly focused path for yourself at a pretty early stage in your career, which is really exciting. I want to hear how you would describe your work and also how your upbringing and your identity has shaped your creative path and the way that you approach your work.

SWC: Well, I have formulated this idea for myself, but I call myself a designer-organizer. My joke is that it’s because I have a hyphenated experience, so I needed another hyphen. But I think also it’s really the acknowledgement that I grew up understanding the capabilities and the limitations of what the built environment can change or not about people’s lives. So I’m not satisfied with that. I wanted from the get-go to have a practice that understood, Okay, these are the actual things that the built environment can influence. How can we organize around those to make them influence more things, better things, and have more power over what actually gets built in the world because it affects so much about how we live and who has access to what.

“I think that Asianis a response to our white supremacist society. It’s only helpful for non-Asians to say that I’m Asian. It’s not quite the, “I’m non-white,” but it’s one step more specific than that. So I don’t really find it that empowering because I think it flattens just the incredible diversity of possibilities.”

So that’s the kind of formation. I got there over many, many years of

thinking about it and witnessing it. Honestly, I struggle with it a lot because

I developed it during my thesis and I was like, “I don’t want to create a new word. We don’t need more

new words; we need action.” But I do think it has been liberating to be like, “Okay,

I can actually consider myself going in parallel with things that already

exist.” I mean, it’s super tied to my identity. Since I am this mixed-race

person who doesn’t have a home that I can go back to, it feels right for me to

have this thing that I’ve invented that doesn’t exist before me because that’s

just who I am as a person.

TSC: I love that.

SWC: And so a lot of it comes from the ethics that I learned at home. They weren’t really explicit, but I think I have a really specific experience being a second-generation designer too. So my mom’s a landscape architect, and she works for the county building greenways. My dad is not a registered architect, which is very specific. He never took the test. So he has technically been an intern for forty years. Again, racial lines. You can just tell who had access to information and the confidence and the money to actually become a licensed professional—my mom versus my dad.

TSC: It’s never too late.

SWC: He would never take the test now. He barely got through school, honestly. But he designs mostly restaurant through retrofits; he actually has crafted this very specific practice for himself within his firm where he pretty much works with first-time restaurateurs who are very often BIPOC immigrants. So he really helps people start businesses, not just designs restaurants for them to go into, which I didn’t really understand and its complexity. I didn’t really admire it, honestly, until I was really thinking about what the field actually asks you to do. Like what you’re doing in these big firms versus not. I just grew up around that.

So it just felt impossible for me to want to graduate and go work at SOM or a big firm and just be told what to do in a very obvious way. And I think also, too, I give my parents a lot of credit. They moved from fancy whatever. My mom graduated from Harvard and then they moved to Charlotte to be close to my grandparents, but also so they could work a nine-to-five. So I’ve actually witnessed a non-exploitative career of being an architect or landscape architect from them. It means you don’t have a flashy client, and it means you work at a really small scale, but you go home at a reasonable time, but you don’t get paid that much. So it’s possible and people do it. But it looks very different for most people who have expectations of themselves coming from these fancy places. I’ve thought a lot about that in terms of both of my parents because they met at Cornell, and then my mom went to Harvard. But they really just didn’t want to do the rat race.

TSC: Are you thinking about that direction? Is that a goal for you to have that kind of a lifestyle where you can do all of these things, but also have a work-life balance?

SWC: Yeah, definitely in the future. I acknowledge it will take some time for me to get there. I mean, I definitely want to teach. My goal is to be a tenured professor. And then hopefully when I get that, have that beautiful—maybe not nine-to-five, maybe it’s ten-to-six—but a more livable work-life balance for sure.

TSC: Have you ever done a project that directly addresses or engages your Chinese, Asian, or mixed-race identity or experiences? I’m thinking about you saying that when you went to RISD, there were a lot of artists who were doing work about their own identity. I know architecture is not as much so identity driven, but I’m curious if you’ve ever done something like that or if you are interested in doing something related to your identity.

SWC: So I have kind of a non-answer, but I feel like it’s really interesting. So, being mixed, like I said, there’s no place in the world I thought where people looked like me and had my identity. I mean, actually, maybe the Bay Area or Cambridge has the highest percentage of white-Chinese people. But there’s, like, not one place. But, after my freshman year at RISD, I actually did an internship in Alaska, in Nome, which is on the Seward Peninsula. It was the most out-of-body experience I’ve ever had because I looked Indigenous. I could be an Inupiaq. People came up to me and spoke to me in Inupiaq. It was such an interesting experience because I actually, for the first time in my life, was surrounded by people that looked like me. And yet—shared English, but didn’t share the native language at home, didn’t share any of our life experiences at all, but they looked like me. So it was so interesting to be in that space, be in the position of representing the National Park Service while doing that, which has done so much harm to Indigenous communities. It was wild. I didn’t really work on that part during my thesis, but I sited my thesis in that area because I wanted to chew on other questions about Indigenous sovereignty and planning and climate change.

But yeah, that is the closest I think I’ve gotten. It was interesting. My best friend, Amanda, is doing her MArch at MIT, and her second studio was about Chinatown. So I got a lot of secondhand thinking about that, and it was when some terrible anti-Asian hate event happened during that studio. So it was, like, really charged, and we had a lot of conversations about it. But again, for me, it’s so muddy. It wouldn’t be a clear project. And that’s really interesting and rich and worth looking and thinking about. But I’ve never done anything like that. I was really interested—and I still am—maybe if my Chinese aunt moves back to Brazil. But I was really interested in the idea of what a diasporic garden looks like, especially in Brazil, because in Brazil, Chinese people are so—as I understand it, they’re quite a tight-knit community and they really have not infiltrated into Brazilian culture. They just keep to themselves. So looking at those spaces, but I don’t have language access. And so I feel like it’s really, really hard for me to do that.

Then I think also just to say I have been in school for a long time, and I’m really cognizant of how schools use students’ work. I don’t want Harvard’s name on anything about people I care about. Let’s keep going because I’m really protective of how people’s identities are just expected to be put on display and researched. So I want to, but I’ll do it on my own time when I’m not in school.

TSC: That’s fair. I think the shift to encourage and promote making work on your own identity has been so recent. I mean, there has always been the exploitation of marginalized communities through research you’re talking about, but in terms of people wanting to explore how their own identity makes its way back into their work, and then schools praising that I think, is definitely a much more recent phenomenon. When I was in school, we were still on that “check your identity at the door—it’s not really relevant in architecture” train. I appreciate what you’re saying, and it’s interesting to hear the projects that you’re thinking about doing that potentially could come into being after you graduate!

I’m curious if you’ve thought about how being racialized as Asian or mixed impacts the work you do. Do you feel like there are challenges that you faced as a Chinese American designer-educator? Have they influenced how you operate in the field or how you feel about yourself and your identity?

SWC: Yeah, totally. So I think going to RISD was also so important because at RISD, Asians—both international student and Asian Americans—are plurality. That was fucking crazy for me, and it made it so that I didn’t feel like I was the token. I was actually representative in a weird kind of perfect fit of like, I did represent the student body. So I think it just unlocked—because I wasn’t like this in high school—it really unlocked me being a leader because I just felt like I could actually understand the systems and speak for people’s experience because they were mine and there were enough people that were similar to me. It just really enabled my ability to understand and to want to fight against systemic harm that was happening at that school. But also, just in general in society, I feel like without being surrounded by so many others, specifically like Asian women at RISD, I wouldn’t have felt so emboldened or I wouldn’t have known the urgency for it.

But I think being in that space, I felt so responsible and so protective of when we did have space, just us. It was so special. Fighting for more of that and fighting—I could fight for my peers in a way I couldn’t when I was in high school, and I felt like that was really, really formational for me and really changed my identity. I switched Myers Briggs at RISD because I just started fighting administration because it was like, “This is bullshit.” So I think I had always walked into rooms understanding that I would be different when I walked into a room. But I think I was able to reclaim it in really interesting ways at RISD—in ways that felt both safe but also powerful. That has really stuck with me since I’ve left.

I was really emboldened. I would just drop f-bombs in every meeting I was in at RISD, and people would be shocked coming from me. I kind of liked the idea that people would underestimate me whenever I came into a room. And then I would say something that would totally catch them off guard and they would be like, “Oh, you’re saying that?” I’d be like, “Yeah, I fuckin am.” So I think that was really empowering because they were shocked enough, but also attentive enough that I felt respected. And so I really, really gained a sense of confidence there that I’ve carried through. And now, I understand how important it is even if I don’t actually feel it to put that on, because I know I’m still—we’re not at the place yet where there are enough Asian women in power, where it’s not so commonplace.

TSC: I love that.

SWC: And so a lot of it comes from the ethics that I learned at home. They weren’t really explicit, but I think I have a really specific experience being a second-generation designer too. So my mom’s a landscape architect, and she works for the county building greenways. My dad is not a registered architect, which is very specific. He never took the test. So he has technically been an intern for forty years. Again, racial lines. You can just tell who had access to information and the confidence and the money to actually become a licensed professional—my mom versus my dad.

TSC: It’s never too late.

SWC: He would never take the test now. He barely got through school, honestly. But he designs mostly restaurant through retrofits; he actually has crafted this very specific practice for himself within his firm where he pretty much works with first-time restaurateurs who are very often BIPOC immigrants. So he really helps people start businesses, not just designs restaurants for them to go into, which I didn’t really understand and its complexity. I didn’t really admire it, honestly, until I was really thinking about what the field actually asks you to do. Like what you’re doing in these big firms versus not. I just grew up around that.

So it just felt impossible for me to want to graduate and go work at SOM or a big firm and just be told what to do in a very obvious way. And I think also, too, I give my parents a lot of credit. They moved from fancy whatever. My mom graduated from Harvard and then they moved to Charlotte to be close to my grandparents, but also so they could work a nine-to-five. So I’ve actually witnessed a non-exploitative career of being an architect or landscape architect from them. It means you don’t have a flashy client, and it means you work at a really small scale, but you go home at a reasonable time, but you don’t get paid that much. So it’s possible and people do it. But it looks very different for most people who have expectations of themselves coming from these fancy places. I’ve thought a lot about that in terms of both of my parents because they met at Cornell, and then my mom went to Harvard. But they really just didn’t want to do the rat race.

TSC: Are you thinking about that direction? Is that a goal for you to have that kind of a lifestyle where you can do all of these things, but also have a work-life balance?

SWC: Yeah, definitely in the future. I acknowledge it will take some time for me to get there. I mean, I definitely want to teach. My goal is to be a tenured professor. And then hopefully when I get that, have that beautiful—maybe not nine-to-five, maybe it’s ten-to-six—but a more livable work-life balance for sure.

TSC: Have you ever done a project that directly addresses or engages your Chinese, Asian, or mixed-race identity or experiences? I’m thinking about you saying that when you went to RISD, there were a lot of artists who were doing work about their own identity. I know architecture is not as much so identity driven, but I’m curious if you’ve ever done something like that or if you are interested in doing something related to your identity.

SWC: So I have kind of a non-answer, but I feel like it’s really interesting. So, being mixed, like I said, there’s no place in the world I thought where people looked like me and had my identity. I mean, actually, maybe the Bay Area or Cambridge has the highest percentage of white-Chinese people. But there’s, like, not one place. But, after my freshman year at RISD, I actually did an internship in Alaska, in Nome, which is on the Seward Peninsula. It was the most out-of-body experience I’ve ever had because I looked Indigenous. I could be an Inupiaq. People came up to me and spoke to me in Inupiaq. It was such an interesting experience because I actually, for the first time in my life, was surrounded by people that looked like me. And yet—shared English, but didn’t share the native language at home, didn’t share any of our life experiences at all, but they looked like me. So it was so interesting to be in that space, be in the position of representing the National Park Service while doing that, which has done so much harm to Indigenous communities. It was wild. I didn’t really work on that part during my thesis, but I sited my thesis in that area because I wanted to chew on other questions about Indigenous sovereignty and planning and climate change.

But yeah, that is the closest I think I’ve gotten. It was interesting. My best friend, Amanda, is doing her MArch at MIT, and her second studio was about Chinatown. So I got a lot of secondhand thinking about that, and it was when some terrible anti-Asian hate event happened during that studio. So it was, like, really charged, and we had a lot of conversations about it. But again, for me, it’s so muddy. It wouldn’t be a clear project. And that’s really interesting and rich and worth looking and thinking about. But I’ve never done anything like that. I was really interested—and I still am—maybe if my Chinese aunt moves back to Brazil. But I was really interested in the idea of what a diasporic garden looks like, especially in Brazil, because in Brazil, Chinese people are so—as I understand it, they’re quite a tight-knit community and they really have not infiltrated into Brazilian culture. They just keep to themselves. So looking at those spaces, but I don’t have language access. And so I feel like it’s really, really hard for me to do that.

Then I think also just to say I have been in school for a long time, and I’m really cognizant of how schools use students’ work. I don’t want Harvard’s name on anything about people I care about. Let’s keep going because I’m really protective of how people’s identities are just expected to be put on display and researched. So I want to, but I’ll do it on my own time when I’m not in school.

TSC: That’s fair. I think the shift to encourage and promote making work on your own identity has been so recent. I mean, there has always been the exploitation of marginalized communities through research you’re talking about, but in terms of people wanting to explore how their own identity makes its way back into their work, and then schools praising that I think, is definitely a much more recent phenomenon. When I was in school, we were still on that “check your identity at the door—it’s not really relevant in architecture” train. I appreciate what you’re saying, and it’s interesting to hear the projects that you’re thinking about doing that potentially could come into being after you graduate!

I’m curious if you’ve thought about how being racialized as Asian or mixed impacts the work you do. Do you feel like there are challenges that you faced as a Chinese American designer-educator? Have they influenced how you operate in the field or how you feel about yourself and your identity?

SWC: Yeah, totally. So I think going to RISD was also so important because at RISD, Asians—both international student and Asian Americans—are plurality. That was fucking crazy for me, and it made it so that I didn’t feel like I was the token. I was actually representative in a weird kind of perfect fit of like, I did represent the student body. So I think it just unlocked—because I wasn’t like this in high school—it really unlocked me being a leader because I just felt like I could actually understand the systems and speak for people’s experience because they were mine and there were enough people that were similar to me. It just really enabled my ability to understand and to want to fight against systemic harm that was happening at that school. But also, just in general in society, I feel like without being surrounded by so many others, specifically like Asian women at RISD, I wouldn’t have felt so emboldened or I wouldn’t have known the urgency for it.

But I think being in that space, I felt so responsible and so protective of when we did have space, just us. It was so special. Fighting for more of that and fighting—I could fight for my peers in a way I couldn’t when I was in high school, and I felt like that was really, really formational for me and really changed my identity. I switched Myers Briggs at RISD because I just started fighting administration because it was like, “This is bullshit.” So I think I had always walked into rooms understanding that I would be different when I walked into a room. But I think I was able to reclaim it in really interesting ways at RISD—in ways that felt both safe but also powerful. That has really stuck with me since I’ve left.

I was really emboldened. I would just drop f-bombs in every meeting I was in at RISD, and people would be shocked coming from me. I kind of liked the idea that people would underestimate me whenever I came into a room. And then I would say something that would totally catch them off guard and they would be like, “Oh, you’re saying that?” I’d be like, “Yeah, I fuckin am.” So I think that was really empowering because they were shocked enough, but also attentive enough that I felt respected. And so I really, really gained a sense of confidence there that I’ve carried through. And now, I understand how important it is even if I don’t actually feel it to put that on, because I know I’m still—we’re not at the place yet where there are enough Asian women in power, where it’s not so commonplace.

“I was like, ‘I don’t want to create a new word. We don’t need more new words; we need action.’ But I do think it has been liberating to be like, ‘Okay, I can actually consider myself going in parallel with things that already exist.’”

So I still feel the need to over-perform

given my identity in a space and project confidence even if I’m not feeling it

because I know I will be discounted based on who I am and what I look like if I’m

coming into a new space. So I definitely carry that with me. It’s a burden that

honestly takes less from me now than it used to. If I sit back and kind of

think about it, it makes me really upset. But it doesn’t take that much energy

from me now because I’ve done it so many times.

But yeah, I definitely feel that kind of responsibility and/or mission to do

things. I understand the

importance of me doing things publicly. It’s still significant that people know

what my work is and what I look like. I don’t want to be separated from

that yet because I think there’s still so much power in that, which again, if

you think about actually what that means, it’s really upsetting. But it’s also

like that’s where we are, so that’s what I do.

TSC: I love that you kind of embrace and like that people underestimate you. It’s almost like it gives you a secret superpower. You’re a superhero, basically. (laughs)

You kind of answered my follow-up question, which is whether you feel like it has benefited or privileged you in any way. I feel like it’s almost all the same thing where you’re like, Yes, these are the challenges that I face. People are underestimating me. People don’t necessarily see me, and they expect more from me because of the way that I’m racialized. But then again, I understand that. So when I understand that I actually have the upper hand and I use that to benefit not only myself but the people that I feel responsible for, that I feel empowered to represent. I think that’s a really incredible way to describe a specific position that Asians have in our racialized society.

SWC: Yeah.

TSC: I want to hear a little bit about your experience of working with Design as Protest and Dark Matter U given that that’s the context that we met. First of all, I’m curious what personal history or experience brought you to DAP and DMU. How did you find out about it? How did you get involved?

SWC: I almost dropped out of architecture my first year, which was confusingly my second year at RISD, because we do like a foundation year or whatever because it was just fucking terrible. It was just like it didn’t mean anything to anyone who was not in the architecture building. So I was really dissatisfied with architecture from the beginning of my schooling and so I did research. I was really—and still am, which I want to bring back into my practice again when I leave Harvard. But I was really, really into community engagement because I was just so annoyed at this fancy school that didn’t actually do anywork or give any benefit back to Providence. So I was looking at firms and found Colloqate online and I was like, Hmm, maybe I should work there.

So there was a list—there was a list of three firms. I didn’t end up working at Colloqate; I ended up working at LA-Más. But it was them two and then Civic Architecture in Chicago were the three nonprofit firms that were nonprofit because they actually wanted to make the world better through architecture. So that’s where I learned about Colloqate and Bryan. Then like everyone else in 2020—well, not like everyone else because I literally graduated from RISD like two days before everything happened. So it was like this whole, “I was moving home; it was a pandemic; I was on Instagram; I was super angry that George Floyd was murdered.” And so that’s kind of how I came to the space. So I didn’t actually know anyone except Kiki, beforehand. We have a super random reason why we know each other.

So it was basically like meeting a whole new set of people, which was really interesting. I mean, there’s so much. I really feel like it was a lifeline for me to this day in the field. I didn’t believe that it was possible to find enough people who cared about what I cared about in the design field that I was like, Maybe I’m going to just do urban planning as a way to have those critical conversations. But yeah, it has been super transformative.

TSC: I love that you kind of embrace and like that people underestimate you. It’s almost like it gives you a secret superpower. You’re a superhero, basically. (laughs)

You kind of answered my follow-up question, which is whether you feel like it has benefited or privileged you in any way. I feel like it’s almost all the same thing where you’re like, Yes, these are the challenges that I face. People are underestimating me. People don’t necessarily see me, and they expect more from me because of the way that I’m racialized. But then again, I understand that. So when I understand that I actually have the upper hand and I use that to benefit not only myself but the people that I feel responsible for, that I feel empowered to represent. I think that’s a really incredible way to describe a specific position that Asians have in our racialized society.

SWC: Yeah.

TSC: I want to hear a little bit about your experience of working with Design as Protest and Dark Matter U given that that’s the context that we met. First of all, I’m curious what personal history or experience brought you to DAP and DMU. How did you find out about it? How did you get involved?

SWC: I almost dropped out of architecture my first year, which was confusingly my second year at RISD, because we do like a foundation year or whatever because it was just fucking terrible. It was just like it didn’t mean anything to anyone who was not in the architecture building. So I was really dissatisfied with architecture from the beginning of my schooling and so I did research. I was really—and still am, which I want to bring back into my practice again when I leave Harvard. But I was really, really into community engagement because I was just so annoyed at this fancy school that didn’t actually do anywork or give any benefit back to Providence. So I was looking at firms and found Colloqate online and I was like, Hmm, maybe I should work there.

So there was a list—there was a list of three firms. I didn’t end up working at Colloqate; I ended up working at LA-Más. But it was them two and then Civic Architecture in Chicago were the three nonprofit firms that were nonprofit because they actually wanted to make the world better through architecture. So that’s where I learned about Colloqate and Bryan. Then like everyone else in 2020—well, not like everyone else because I literally graduated from RISD like two days before everything happened. So it was like this whole, “I was moving home; it was a pandemic; I was on Instagram; I was super angry that George Floyd was murdered.” And so that’s kind of how I came to the space. So I didn’t actually know anyone except Kiki, beforehand. We have a super random reason why we know each other.

So it was basically like meeting a whole new set of people, which was really interesting. I mean, there’s so much. I really feel like it was a lifeline for me to this day in the field. I didn’t believe that it was possible to find enough people who cared about what I cared about in the design field that I was like, Maybe I’m going to just do urban planning as a way to have those critical conversations. But yeah, it has been super transformative.

“I understand the importance

of me doing things publicly. It’s still significant that people know what my

work is and what I look like.”

Interview Segment: What my work is and what I look like

I don’t know about my identity. I mean, I think at first, to be really

honest—again, because it was 2020, I was like, Okay, well, I’m racialized, but

I’m not Black. So I’m just going to sit here and listen and let all the Black

people talk and I’ll listen and do whatever is helpful, which I think is a fine

way to start. I don’t think that’s bad. After time and after trust and

relationships were built, I think it’s like—because I don’t think that’s

actually that unhealthy, but I

think it’s very much now about the relationships versus I think initially it

was like kind of proving that you’re coming correct to a space. And there’s

more to prove that you’ve undone a lot of thinking when you are Asian, coming

to a BIPOC-only space. So trying to take that kind of responsibility seriously

of making sure that I knew my shit before I came to a space where other

racialized people were also there and experiencing different traumas than I was,

I think, was important.

And then it has just been a really interesting way to think about power building in kind of both spaces. As someone who wants to go into academia, it has also been really interesting to see DMU and how power operates in DMU. Neither organization is perfect. There are still isms present, but I think the idea that everyone is actively working on those “isms” is just like a space of hope for me if anything. And then also, like I said, my dad doesn’t talk about his identity ever. So it’s not elders but people who were comfortable talking about their identities and how it affected their life who were in the field has been so valuable too, to me.

TSC: I’m curious if you’ll say a little bit more about that experience of kind of showing up to the space as a non-Black POC. What were you thinking about when you showed up and you were like, “I want to make sure that I come correct.” What did that mean to you and has that feeling evolved over time?

SWC: Yeah, definitely. I mean, I was trying to figure it out when it was happening. But I think honestly for me, it was a number of things. It was understanding the kind of history of racialization in the US. For me, it was interesting too because I was in the Northeast coming back south. So I do have a lot of information growing up of like—the Black southern experience was really close to me growing up. So that proximity was there.

But I think as much as learning about externalities, it was also about learning about how I came to be. Like I said earlier, being Asian doesn’t cut it because the Asian experience is so specific. Oppression of Asian people in the US depends on when you came, depends on what you had access to, depends on if you had papers, when you got papers. So honestly, coming correct was also me thinking about my specific privileges and oppression that happened in my family that can be traced. And understanding those I feel like—didn’t give me credibility, but just makes solidarity so much stronger. When you can name the things that have happened to yourself, you’re kind of sharing that language but also understanding how the systems affected other people differently. It’s understanding that my dad came to the US after 1965. So all of these Black and brown organizers did all this work to make it legal for my dad to come with papers. But the fact that he had to be in Brazil for thirteen years is also a thing.

And then it has just been a really interesting way to think about power building in kind of both spaces. As someone who wants to go into academia, it has also been really interesting to see DMU and how power operates in DMU. Neither organization is perfect. There are still isms present, but I think the idea that everyone is actively working on those “isms” is just like a space of hope for me if anything. And then also, like I said, my dad doesn’t talk about his identity ever. So it’s not elders but people who were comfortable talking about their identities and how it affected their life who were in the field has been so valuable too, to me.

TSC: I’m curious if you’ll say a little bit more about that experience of kind of showing up to the space as a non-Black POC. What were you thinking about when you showed up and you were like, “I want to make sure that I come correct.” What did that mean to you and has that feeling evolved over time?

SWC: Yeah, definitely. I mean, I was trying to figure it out when it was happening. But I think honestly for me, it was a number of things. It was understanding the kind of history of racialization in the US. For me, it was interesting too because I was in the Northeast coming back south. So I do have a lot of information growing up of like—the Black southern experience was really close to me growing up. So that proximity was there.

But I think as much as learning about externalities, it was also about learning about how I came to be. Like I said earlier, being Asian doesn’t cut it because the Asian experience is so specific. Oppression of Asian people in the US depends on when you came, depends on what you had access to, depends on if you had papers, when you got papers. So honestly, coming correct was also me thinking about my specific privileges and oppression that happened in my family that can be traced. And understanding those I feel like—didn’t give me credibility, but just makes solidarity so much stronger. When you can name the things that have happened to yourself, you’re kind of sharing that language but also understanding how the systems affected other people differently. It’s understanding that my dad came to the US after 1965. So all of these Black and brown organizers did all this work to make it legal for my dad to come with papers. But the fact that he had to be in Brazil for thirteen years is also a thing.

“I think it’s very much now

about the relationships versus I think initially it was like kind of proving

that you’re coming correct to a space. And there’s more to prove that you’ve

undone a lot of thinking when you are Asian, coming to a BIPOC-only space.”

Interview Segment: Coming correct to a BIPOC-only space

So understanding those dynamics is how I felt like I was able to then be

a contributing—or not a contributing—but just felt like I could have those

deeper discussions with people. Along with all of the miseducation that I’d

given myself at RISD, too, where I was like, Okay, this is what I’m learning in

class. This is what I’m learning because I care about it and I think it’s

important outside of the classroom, which is more of the like, Okay, this is

how the built environment can perpetuate racism in so many ways. That wasn’t,

like, a new concept for me, but it was like, “How do I fit into my

understanding of this?” was how I needed to make myself come correct to DAP.

TSC: Yeah, definitely. Have you ever experienced resistance to your presence or role in racial justice or solidarity work?

SWC: I’m sure I have. It hasn’t been to my face, which I think is really interesting. There’s a ton of reasons for that. I try really hard to make it hard for someone to question why I’m in a space. I think that’s no small part of that.

TSC: Can you say a few more words about that? What do you mean by that?

SWC: I don’t know. I guess I take the work really seriously, and I feel like I’m pretty responsive. So if someone were to call me out or call me in, I feel like—it really just hasn’t happened, which is kind of wild. I am very surprised by that. I think about it happening a lot before I’m, like, a public figure or whatever, so I’m ready. But it hasn’t happened, which I guess is cool and good. I’m okay if it does happen. But yeah, I think about my positionality a lot and my power to say yes and my power to say no to things too. So I take it really seriously but I’m not immune to it.

TSC: I want to hear a little bit about what dreams or aspirations you have for Asian and Chinese diaspora spaces and the people who are shaping them through design.

SWC: So many. (laugh) I think honestly the biggest one for me that isn’t race specific is I want to be an educator because I learned design from my parents. And when I learned design from my parents, it wasn’t punitive; it wasn’t stressful; it wasn’t competitive. It was just, like, people who like making things. I just really, really want to empower anyone who does like making things to be able to live in a world where they do that for their job. That’s my goal for design education is to have people self-actualize through the creation of space. Something that I’ve been working on with a professor at UVA, which is why I started working with her—is because she has this theory called “student at site,” where to be a good teacher, you have to understand where someone is coming from as, like, a thickened section of different layers of histories and identities, and that your identity is never apart from what you’ve made. So, I think for me, the goal is that becomes, like, a standard thing that people don’t have to make work about their trauma, but their identity is baked into it.

Then I think a larger goal just in terms of architecture and design is to bring authentic culture building back—modernism stripped culture from design. So how do we bring back regionality or specific cultural design that is responsive to religion or other forms of identity in a way that’s authentic and beautiful and not flattening—is something that I really think about a lot because I grew up in suburbia. It’s terrible. It’s just actually bad design on so many levels.

Culture is so beautiful and empowering and really helpful, and there’s so much to learn from. So I think taking culture seriously—again, and depending on who is doing this, it looks totally different. But taking that seriously in an academic sense I think is a goal that plays into identity. But everyone has an identity, and it takes that seriously in a way that I don’t want to just fetishize Asian people. I don’t want another Chinatown Archway. But people really taking seriously the values that they grew up with and trying to spatialize them, I think, is a really interesting thing that I don’t hear a lot about.

TSC: Can you dream up a project? Would you want to get together with people and try to spatialize some sort of collective values? Have you dreamt about how that would express itself in a built project you might do?

SWC: Yeah. Well, me and Amanda talked about co-parenting for a really long time. So I feel like the spatial dynamics of co-parenting would be really interesting with two mixed-race people from different mixes—would be really cool. So, I guess, housing.

TSC: That’s interesting!

SWC: I mean, kind of any project.

TSC: I love that—that’s a life project more than an architecture project.

SWC: Well, it could be both! Like, What’s the house that we live in together that’s separate but a part? As I get older (laughs)—in the last year, I am realizing that I love—which is why I think teaching will be good for me—is that I love thinking about projects. But the idea of actually drawing a construction set or even drawing a plan is not that interesting to me. I like talking about other people’s plans, but I’m like, “I don’t need to do it myself.”

TSC: Yeah. I think you’re going in the right direction then, because professors love to talk and comment on other people’s work. An important component of this project is to create resources that’ll be useful for other Asian American, Asian diaspora designers and creatives. I’m curious what resources you would love to see for other Asian designers, or maybe what would you have loved to have seen as a younger designer?

SWC: So one big one is that I got really mad, I guess last year, because they teach design discovery at Harvard, which is, like, this summer thing. It’s like InARCH at Berkeley or something. Anyways, I was at the library, and I looked at the reading list and it was literally—for landscape architecture—I think there was like two people of color on the whole stack of forty books. So I started something, and I haven’t gone back to it because I haven’t had time. And Michelle added to it and I think Kiki added to it—but a really comprehensive list of BIPOC landscape architects does not exist. Architecture has a list of people. I feel like it has been crowdsourced a little bit, but literally, there are not enough books on BIPOC landscape architects. That’s for a number of reasons. The field is newer. A lot of people don’t consider themselves landscape architects in other countries. But really, there’s just a gap. There’s a huge gap. And maybe me and Maria will write a book or something—that would be cool. But there’s a huge gap on that.

But I think for me as a young—in my undergrad, if DAP existed, I would be different even. If DAP existed three years earlier, I would be a different person just, like, having that. So I think just having a network of people that feel accessible is super important. Not as concrete, but just more of it. There was a DMU session at the Design Justice Summit where we’re talking about educators and I just can’t get out of my head how upsetting having—so I had a very well-known BIPOC professor my second semester of architecture school. And at the end I was like, “We’re not doing anything useful. Why am I in this school? I should transfer.” He told me that I’m too good of a designer to not be an architect. It was just a terrible, terrible answer.

Now, I will give him grace. So I think for students just understanding the complexities of the power structures where he felt like he couldn’t do the research he wanted to do, support students the way that they needed to be supported

TSC: So he said to you, “You’re too good of a designer.” Can you explain that conversation a little bit more? I don’t think I fully understand.

SWC: Well, I was like, “This isn’t doing anything. The studio is terribly designed. We’re not building for people; we’re just building a form. If I want to do real community impact, I feel like I should not be in architecture school.”

TSC: Got it.

SWC: And basically, he wasn’t like, “Make architecture better.” He was like, “But you are too good at it. You should just keep doing it.” And I was like, “What?”

TSC: That’s interesting. I think it’s good to give people a little bit of grace because I do think that there was a certain point where it’s likely that he didn’t feel safe or empowered to do the things that he really wanted to do. Also, I’ve heard some older professors talk about how they didn’t want to be permanently labeled as the “whatever marginalized identity you hold” professor. They wanted to actually gain some ground through being an architecture professor and not being, like, the “insert identity” architecture professor. It’s been more recent that they’re more comfortable being like, Okay, now I can actually look into things that are more relevant to the intersections between my interests and my personal identity or positionality.

SWC: But you got to throw students a lifeline. Like, come on. Give me twenty minutes. Say, “Okay, I can’t help you, but there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.” Encouragement costs nothing. To just be like, “Sophie, keep asking these questions; they’re really important.” That would’ve meant so much to me, and I didn’t hear that from him. I’m just like, Why? I know there was a bunch of students that needed that from him.

Again, I wish him super well, but it was just frustrating because he wasn’t who I wanted him to be. I was mad at the whole situation. I don’t blame him for it, but it was just like we were both casualties in it, I think.

TSC: Absolutely. It’s also hard when you’re the only one and people expect things of you and they gravitate towards you because you are that one. They need mentorship or guidance and they identify you as being someone who can give it to them. If you are just not in that space mentally, emotionally, and intellectually to offer that, then that’s hard too.

SWC: Totally, yeah. I have a lot of respect for him.

TSC: This is kind of like we’re near the end of our hour. I’m wondering if there’s any projects or initiatives that you’re working on that you’re excited about that you want to share?

SWC: I don’t know. What am I working on?

TSC: I mean, you’re doing a residency right now. You’re working on probably twenty things. I’m just going to take a wild guess. (laughs)

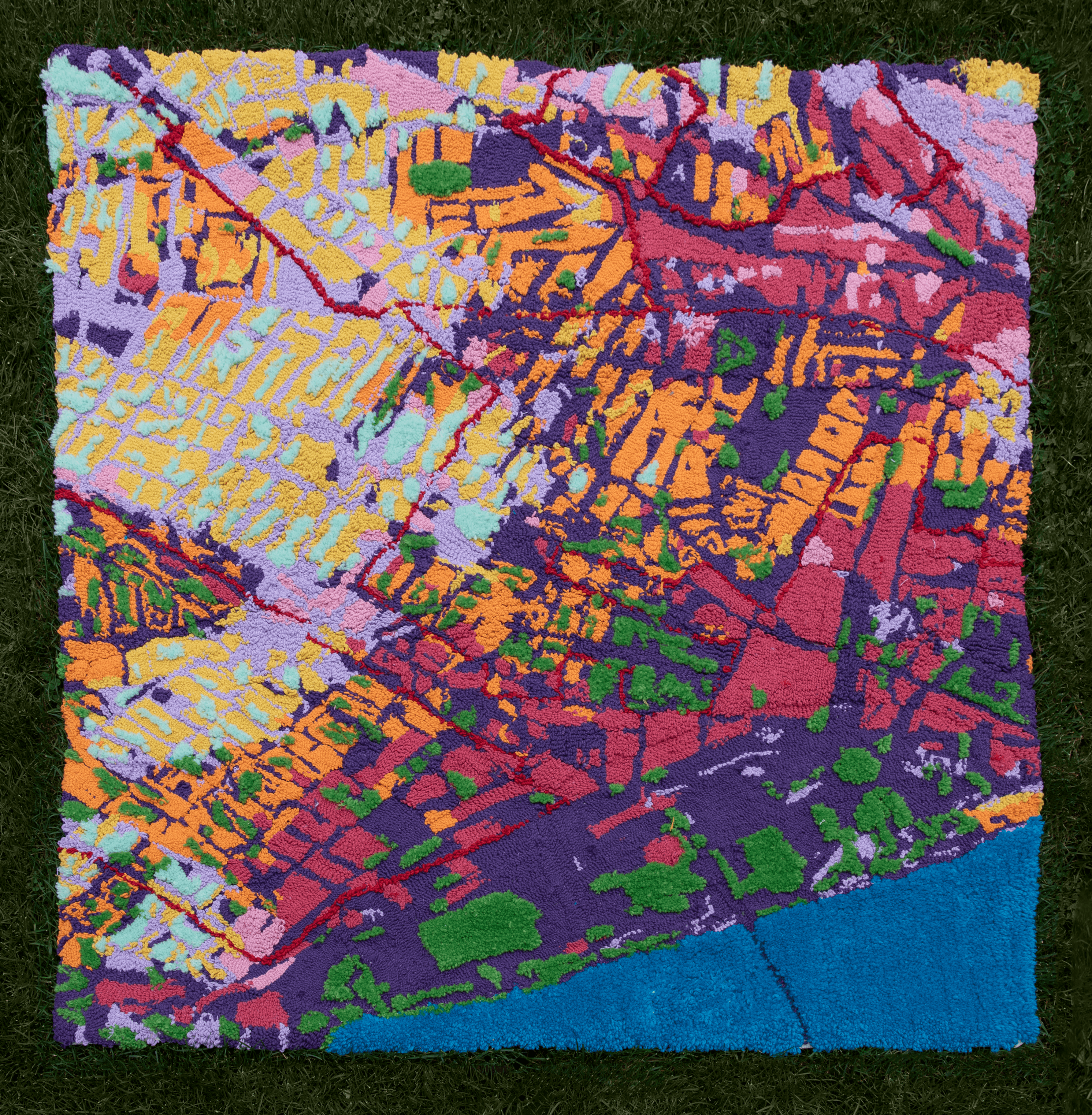

SWC: I guess. So in the residency—so I did a project with Amanda on tufting called Soft City, trying to understand how to make cities more approachable. So I think from that I learned the importance of communication devices. And so that’s what I’m calling what I’m doing. I’m making communication devices about ecological problems. I’m doing a piece that’s trying to explain the harm that lawns do to ecosystems. They provide zero services. They’re like toilet paper; they’re terrible. And so it’s like, How do you explain the value of native pollinators, versus a lawn, versus moss? And using tufting as the medium to do that because again—but I just feel like it’s meeting people more where they’re at in terms of accessing information that’s spatial because people like to touch soft things. On that very basic level it’s like if you can engage with people and it feels like they can enjoy something, they’re more likely to learn from it. So how do you make tough things, make these big scary concepts like climate change, and bring people into the conversation in a way that’s not a graph that just is exponential doom.

In Soft City, me and Amanda were talking about the legacy of race and redlining in the built environment. We were trying to figure out different ways to bring people into conversations and different ages too because I feel like having it be tactile is a way that kids learn, but not really adults. So how do you make that learning actually possible for all ages?

TSC: Yes. As someone with an eight-month-old, I can confirm that they love to touch things. There’s all these touch-and-feel books—

SWC: And be more playful! That’s one of the things I’m working on. I’m working on getting a tenure-track job—is also what I’m working on. (laughs)

TSC: So you can be that mentor that you needed when you were a student.

SWC: Yeah. But also, I guess it is interesting the politics of applying to academic jobs have been kind of a lot to navigate. Basically, I’m also trying to figure out the kind of politics of me claiming or not claiming Brazilian as a valid heritage. Again, because it’s like honoring the country that let my family in before the United States did. But it’s also like the racial history of Brazil is so specific. So I don’t know if I’m misrepresenting or reclaiming that identity by checking a box. Obviously, it’s super flattening anyway to check a box for any reason. So that’s also something I’ve been chewing on in terms of like, What does it mean for me to do that versus not? Is that giving them diversity numbers that maybe aren’t represented? Yeah, I don’t know. It has been a big question.

TSC: It is really complicated now when you are thinking about whether or not you can claim an identity not just for yourself, but also just because there’s, like, funding and positions and money attached to holding certain identities that have been underrepresented—for good reason. It makes that question really heavy of “Can I really claim this identity? Am I really doing what we’re trying to do here?” I think that one thing that I’ve really considered is that identity can be fluid in how you represent yourself and the parts of your identity in certain spaces can change. It doesn’t have to just be one thing. You can be like, “I claim this identity sometimes in these spaces and then in these circumstances I don’t because I feel that it misrepresents or misaligns with my values.”

SWC: Yeah, definitely. I never feel more Brazilian except when I’m around Chinese people because I’m like, I’m Chinese Brazilian to you because you’re all Chinese, which is, like, really interesting.

TSC: Okay, my final final question is just if there’s anything else you would like to share or to revisit from our conversation?

SWC: I don’t know. I guess it has been a lot over the last few years, and I feel like I just have more empathy for my parents navigating what they navigated, I think. Especially with Everything Everywhere All at Once and the media representation of actually what it has been like as kids to grow up with immigrant parents or like marrying an immigrant. I feel like the work required for that type of relationship and to build a family in that way is a lot. It’s heavy and I feel like you don’t have an option, but it’s still kind of a lot to deal with. So I just feel like I have more empathy for my parents for going through that, and then also as built environment practitioners, too, holding those things.

TSC: Well, thank you so much. I appreciate it.

TSC: Yeah, definitely. Have you ever experienced resistance to your presence or role in racial justice or solidarity work?

SWC: I’m sure I have. It hasn’t been to my face, which I think is really interesting. There’s a ton of reasons for that. I try really hard to make it hard for someone to question why I’m in a space. I think that’s no small part of that.

TSC: Can you say a few more words about that? What do you mean by that?

SWC: I don’t know. I guess I take the work really seriously, and I feel like I’m pretty responsive. So if someone were to call me out or call me in, I feel like—it really just hasn’t happened, which is kind of wild. I am very surprised by that. I think about it happening a lot before I’m, like, a public figure or whatever, so I’m ready. But it hasn’t happened, which I guess is cool and good. I’m okay if it does happen. But yeah, I think about my positionality a lot and my power to say yes and my power to say no to things too. So I take it really seriously but I’m not immune to it.

TSC: I want to hear a little bit about what dreams or aspirations you have for Asian and Chinese diaspora spaces and the people who are shaping them through design.

SWC: So many. (laugh) I think honestly the biggest one for me that isn’t race specific is I want to be an educator because I learned design from my parents. And when I learned design from my parents, it wasn’t punitive; it wasn’t stressful; it wasn’t competitive. It was just, like, people who like making things. I just really, really want to empower anyone who does like making things to be able to live in a world where they do that for their job. That’s my goal for design education is to have people self-actualize through the creation of space. Something that I’ve been working on with a professor at UVA, which is why I started working with her—is because she has this theory called “student at site,” where to be a good teacher, you have to understand where someone is coming from as, like, a thickened section of different layers of histories and identities, and that your identity is never apart from what you’ve made. So, I think for me, the goal is that becomes, like, a standard thing that people don’t have to make work about their trauma, but their identity is baked into it.

Then I think a larger goal just in terms of architecture and design is to bring authentic culture building back—modernism stripped culture from design. So how do we bring back regionality or specific cultural design that is responsive to religion or other forms of identity in a way that’s authentic and beautiful and not flattening—is something that I really think about a lot because I grew up in suburbia. It’s terrible. It’s just actually bad design on so many levels.