“We do have the space to create this collective political identity and it's always changing. Why not sort of opt into it and give it form, give it visibility, instead of just being like, Mm-hmm, let me just continue to choose which world to fit into?”

she/her

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I'm here with Theresa Hyuna Hwang for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora. So tell me a little bit about your identity as Corean and as Asian American and how it has played a role in your experience growing up. What was your family home like? What was your neighborhood like? Did you grow up around other Coreans or Asians or immigrant families?

Theresa Hyuna Hwang (TH): So I feel very fortunate. I grew up in a very robust Corean immigrant community. It's so funny when people ask, Where are you from? Where did you grow up? I think it very much mirrors this hyphenated identity of Asian American, where I always tell people like, “I grew up in Long Island and Queens.” Our home was in a suburb outside of New York City, where I went to school, predominantly white school where there were a handful of Black, Latino, and Asian folks in it. But then my parents worked in Queens. We went to church in Queens. I went to Corean school, and so spent a lot of our free and community time there. I feel like a lot of my identity around being Corean was always very celebrated, but I was always surrounded by it. So in many ways it's like had a foot in multiple different neighborhoods and different institutions that I think either challenged or affirmed what my identity was.

My parents immigrated to the US in the late seventies. My older sister was born in Corea, and I'm the first person in our family to be born in the US away from ancestral homelands. So we were in a household where my parents made it very explicit that it was important for us to know where we came from. And so we spoke Corean at home, only ate Corean food at home. We went to Corean school every Saturday. And so very much sort of nationalistic in that we know where we come from, know our history, but also, my parents made sure we knew how to read and write, and even though it's only like on a third-grade level, have some sort of formal connection to, I think, where we came from.

So I feel fortunate that I had other second-gen Corean folks around me—so very similar people our age where we had our immigrant parents speak to us in one language and then we would respond in English and then mix everything all together. So being Corean was really a big part of who I was. It wasn't until probably like high school—but then really college—that I started to lean into the identity of being Asian American and sort of understanding the politicized roots behind that.

TSC: I would love to hear a little bit more about that transition from identifying as very strongly Corean, growing up in a Corean immigrant family, to leaning into a new political identity as Asian American. Was there a moment where there was a shift, or was it a slower process? What is your relationship to the term Asian or Asian American today? Do you feel that that label or identity empowers you or limits you in any way? Does it bring you a sense of belonging?

TH: Going to school where it was predominantly white, I feel like naturally students of color, or for me, other Asian students, there was an affinity. Even growing up, I remember in our neighborhood, there were just a handful of other Chinese American, Asian American girls my age actually in the same grade as me. And so because by proximity we lived in the same neighborhood too, I think we just naturally gravitated towards each other. So there was just almost like an instinctive, We are similar. And whether it was possibly because it was imposed where the teacher would call us by the wrong name at times. But, also from within, there was just, like, a more shared understanding around like, Okay, we don't have to be embarrassed about the way our houses smell when we go to each other's houses.

So I was lucky growing up. I did have other Asian American friends. I think growing up in New York, middle school, high school, there was always that thing of, like, Asians only hang out with each other. But you could say the Latino students all hung out with each other, and there was definitely just a deep awareness of that. Like I knew growing up—I was friendly with everybody, but the people that I primarily spent my free time with were Asian American. And then again, having this core pillar in the Corean community where my closest friends typically were Corean. So I think there was just a natural sort of desire for a collective belonging. And so gravitating to other Asian American folks was something that from a very young age I had.

Then I think it really was when I started to go to college—I’m also really lucky, I have an older sister. She's three years older, and so when I was in high school and she was in college and she's taking ethnic studies, a lot of what she learned would filter down to me. So I even remember like in junior year in US history class, we had to write a paper and my sister heavily influenced me with, I think, what she was learning. I wrote a paper on Vincent Chin in Detroit and, like, Asian Americans taking a stand. And I think that was probably the first time I started to research, like read articles, read books as it relates to an intentional Pan-Asian identity. So that was the first time where I started to see these signs of, like, political solidarity in the Asian diaspora in reaction to a hate crime that happened in Detroit. And then also recognizing these types of vulnerabilities are also experiences—are also shared.

Growing up my dad would always point out when we were treated poorly because we were Asian. So if we would go to, like, an Italian restaurant, they would, like, always seat us in the back or next to the bathroom. My dad would always say loudly like, “Why are we sitting here? All these tables in the front are empty,” and would demand a better seat. I used to be so embarrassed because he'd be really loud and his accented English. But there was also an awareness of calling out when we were discriminated against. So I think recognizing there was a shared struggle and then feeling a sense of power when there is just a greater mass. There are certain limitations when, like, I'm just gravitating to Corean diaspora. And so I think when I went to college, there was a lot more diversity. I went to college where there were—it was still predominantly white institution, but it was like 10 percent Black and then like 20 percent Asian.

So because there were more students of color, I started to also see sort of now even a wider range of what the diaspora was and became a campus organizer. And I think it was through that lens of really just trying to, I think, embrace what the political power could be when you are connected and mobilized with more people. In high school we had, like, Asian night where it was more about multiculturalism and sharing culture. Whereas I think, when I went to college, it was more about like, “These are institutional discriminations that we're facing. What are we going to do in response to—or what are some of the things that we want to shift in this world so that there's more space for us?”

So I really learned through ethnic studies, like, Asian American is a political identity. It was designed in the heat of the sixties, seventies, like Third World radical resistance, revolutionary movements of intentionally building power. And so for me it was always a sense—it wasn't just like, Oh, I happen to be Asian. It's like, I'm choosingto be Asian American because I feel stronger being in relationship to all these other folks. I think in that sense it created a greater sense of—beyond safety, like you said, but belonging in the US. So much of racial dynamics are just on the Black and white binary. And then also just really being aware. I grew up in New York and listened to hip-hop. There was always like, “You got to choose. Are you going to listen to rock and roll? Are you going to listen to hip-hop?” There was always like a, “Whose culture do you feel closer to?” Because we were never depicted in media, TV, music, or anything like that. So there was more of like, “Okay, then who do you feel closer to?” Whereas I think in college I started to see more and learn about the cultural production, like the very Asian Americanness of cultural workers, and people who made music, and writers, and poets that did represent this Asian American identity. So definitely college was a big chance, I think, for me to just step into a role of what organizing—and also now, like, starting to bring people together that were like-minded.

Tonia Sing Chi (TSC): This is Tonia Sing Chi, and I'm here with Theresa Hyuna Hwang for Storytelling Spaces of Solidarity in the Asian Diaspora. So tell me a little bit about your identity as Corean and as Asian American and how it has played a role in your experience growing up. What was your family home like? What was your neighborhood like? Did you grow up around other Coreans or Asians or immigrant families?

Theresa Hyuna Hwang (TH): So I feel very fortunate. I grew up in a very robust Corean immigrant community. It's so funny when people ask, Where are you from? Where did you grow up? I think it very much mirrors this hyphenated identity of Asian American, where I always tell people like, “I grew up in Long Island and Queens.” Our home was in a suburb outside of New York City, where I went to school, predominantly white school where there were a handful of Black, Latino, and Asian folks in it. But then my parents worked in Queens. We went to church in Queens. I went to Corean school, and so spent a lot of our free and community time there. I feel like a lot of my identity around being Corean was always very celebrated, but I was always surrounded by it. So in many ways it's like had a foot in multiple different neighborhoods and different institutions that I think either challenged or affirmed what my identity was.

My parents immigrated to the US in the late seventies. My older sister was born in Corea, and I'm the first person in our family to be born in the US away from ancestral homelands. So we were in a household where my parents made it very explicit that it was important for us to know where we came from. And so we spoke Corean at home, only ate Corean food at home. We went to Corean school every Saturday. And so very much sort of nationalistic in that we know where we come from, know our history, but also, my parents made sure we knew how to read and write, and even though it's only like on a third-grade level, have some sort of formal connection to, I think, where we came from.

So I feel fortunate that I had other second-gen Corean folks around me—so very similar people our age where we had our immigrant parents speak to us in one language and then we would respond in English and then mix everything all together. So being Corean was really a big part of who I was. It wasn't until probably like high school—but then really college—that I started to lean into the identity of being Asian American and sort of understanding the politicized roots behind that.

TSC: I would love to hear a little bit more about that transition from identifying as very strongly Corean, growing up in a Corean immigrant family, to leaning into a new political identity as Asian American. Was there a moment where there was a shift, or was it a slower process? What is your relationship to the term Asian or Asian American today? Do you feel that that label or identity empowers you or limits you in any way? Does it bring you a sense of belonging?

TH: Going to school where it was predominantly white, I feel like naturally students of color, or for me, other Asian students, there was an affinity. Even growing up, I remember in our neighborhood, there were just a handful of other Chinese American, Asian American girls my age actually in the same grade as me. And so because by proximity we lived in the same neighborhood too, I think we just naturally gravitated towards each other. So there was just almost like an instinctive, We are similar. And whether it was possibly because it was imposed where the teacher would call us by the wrong name at times. But, also from within, there was just, like, a more shared understanding around like, Okay, we don't have to be embarrassed about the way our houses smell when we go to each other's houses.

So I was lucky growing up. I did have other Asian American friends. I think growing up in New York, middle school, high school, there was always that thing of, like, Asians only hang out with each other. But you could say the Latino students all hung out with each other, and there was definitely just a deep awareness of that. Like I knew growing up—I was friendly with everybody, but the people that I primarily spent my free time with were Asian American. And then again, having this core pillar in the Corean community where my closest friends typically were Corean. So I think there was just a natural sort of desire for a collective belonging. And so gravitating to other Asian American folks was something that from a very young age I had.

Then I think it really was when I started to go to college—I’m also really lucky, I have an older sister. She's three years older, and so when I was in high school and she was in college and she's taking ethnic studies, a lot of what she learned would filter down to me. So I even remember like in junior year in US history class, we had to write a paper and my sister heavily influenced me with, I think, what she was learning. I wrote a paper on Vincent Chin in Detroit and, like, Asian Americans taking a stand. And I think that was probably the first time I started to research, like read articles, read books as it relates to an intentional Pan-Asian identity. So that was the first time where I started to see these signs of, like, political solidarity in the Asian diaspora in reaction to a hate crime that happened in Detroit. And then also recognizing these types of vulnerabilities are also experiences—are also shared.

Growing up my dad would always point out when we were treated poorly because we were Asian. So if we would go to, like, an Italian restaurant, they would, like, always seat us in the back or next to the bathroom. My dad would always say loudly like, “Why are we sitting here? All these tables in the front are empty,” and would demand a better seat. I used to be so embarrassed because he'd be really loud and his accented English. But there was also an awareness of calling out when we were discriminated against. So I think recognizing there was a shared struggle and then feeling a sense of power when there is just a greater mass. There are certain limitations when, like, I'm just gravitating to Corean diaspora. And so I think when I went to college, there was a lot more diversity. I went to college where there were—it was still predominantly white institution, but it was like 10 percent Black and then like 20 percent Asian.

So because there were more students of color, I started to also see sort of now even a wider range of what the diaspora was and became a campus organizer. And I think it was through that lens of really just trying to, I think, embrace what the political power could be when you are connected and mobilized with more people. In high school we had, like, Asian night where it was more about multiculturalism and sharing culture. Whereas I think, when I went to college, it was more about like, “These are institutional discriminations that we're facing. What are we going to do in response to—or what are some of the things that we want to shift in this world so that there's more space for us?”

So I really learned through ethnic studies, like, Asian American is a political identity. It was designed in the heat of the sixties, seventies, like Third World radical resistance, revolutionary movements of intentionally building power. And so for me it was always a sense—it wasn't just like, Oh, I happen to be Asian. It's like, I'm choosingto be Asian American because I feel stronger being in relationship to all these other folks. I think in that sense it created a greater sense of—beyond safety, like you said, but belonging in the US. So much of racial dynamics are just on the Black and white binary. And then also just really being aware. I grew up in New York and listened to hip-hop. There was always like, “You got to choose. Are you going to listen to rock and roll? Are you going to listen to hip-hop?” There was always like a, “Whose culture do you feel closer to?” Because we were never depicted in media, TV, music, or anything like that. So there was more of like, “Okay, then who do you feel closer to?” Whereas I think in college I started to see more and learn about the cultural production, like the very Asian Americanness of cultural workers, and people who made music, and writers, and poets that did represent this Asian American identity. So definitely college was a big chance, I think, for me to just step into a role of what organizing—and also now, like, starting to bring people together that were like-minded.

Interview Segment: It's one thing to decenter

yourself and then it's another thing to obscure yourself

INTERVIEW 15 DETAILS

Narrator:

Theresa Hyuna Hwang, she/her

Interview Date:

March 15, 2024

Keywords:

Themes: Corean identity, Black and white binary,ethnic studies, anti-war demonstrations, traditional Corean folk drumming, Boston, Spoken word poetry, affordable housing, decentering, belonging, Black power movement, preservation, farm worker movement, civil rights movement

Places: Corea, Long Island, Queens, New York, Los Angeles, Skid Row, Little Tokyo, East Los Angeles, South Central

References: Vincent Chin, Yuri Kochiyama, Grace Lee Boggs, East West Players, A Grain of Sand, Black Panthers, Living for Change

ABOUT THERESA

Ancestral Land:

Corea

Homeland:

Lenapehoking (New York)

Current Land:

Tovaangar (Los Angeles)

Diaspora Story:

My parents immigrated to the US (Queens, NY) in 1978. In 1979, I was the first person in my family to be born in the US off of ancestral lands. I grew up in a strong Corean immigrant community in Queens where cultural practices were embraced and integrated into my everyday life. I attended a predominantly white school on Long Island where I changed my name from Hyuna to Theresa in the first or second grade because white boys at school would tease my Corean name. I learned at an early age how to code switch.

Creative Fields:

architecture, urban planning, community development, public art

Racial Justice Affiliations:

APIA spoken word and poetry summit, Boston Progress Arts Collective, Color the Water, Design Futures

Favorite Fruit:

wild blueberries

Biography:

Theresa Hyuna Hwang (she/her) is a

community-engaged architect, educator, and facilitator. She has spent over 20

years focused on equitable cultural and community development across the United

States. Theresa/Hyuna holds spaces of mindful dialogue to address collective

neighborhood-based trauma and collectively design radical solutions based on

first-hand experiences, centering folx who are most impacted. She is the

founder of Department of Beloved Places, a participatory architecture practice

based on occupied Tongva Land (Los Angeles, CA). She is a trauma-informed and

non-violent communication parenting educator and a dedicated mindfulness

practitioner in the Plum Village tradition of Thich Nhat Hanh.

She received her Master of Architecture from Harvard Graduate School of Design

(2007) and a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering and Art History from the

Johns Hopkins University (2001). She is a licensed architect in California.

︎

deptofplaces.org

︎ @DEPTOFPLACES

Then I

would say once I graduated college, I moved back home to New York. It's like

2001: Moved back to New York; 9/11 happens—and being in the city trying to find

my first real job fresh out of college. New York was also an intensely

politically charged place to be. In college, I supported sort of like—I remember

going on my first march and protests to support a living wage. Back in even

like 1999, we were talking about a living wage. But I remember moving back to

New York, and specifically post-9/11 New York, and just seeing the anti-Muslim

sentiment, the rise in US imperialism, the indiscriminate bombing of

innocent folks who were in West Asia, in the Middle East,

however you want to see, like, oppressed peoples. There was just

more shared understanding of like, That's closer to us.

So that was when I first started to attend public demonstrations—anti-war demonstrations. And then in those venues always joining either the people of color contingent, learning that people of color is also a very highly politicized intentional identity that people choose to opt into. But, also, I started again through my sister, who I've been so lucky to have like a great teacher to just show me so many different things, but also came into traditional Corean folk drumming. I mean, I'm sure you see now in protests the Corean drummers are always out in any type of demonstration. So that was a practice that I started to connect to sort of ancestral homelands, to agriculture, farm work, folk cultural traditions. But, also, it made me feel like I fit in or had a role in some of these demonstrations and just to show up in your full drumming garb and having a voice and then be surrounded by like, let's say, an Asian American contingent. It felt so powerful.

I think when I attended rallies in the past, I always felt still very marginalized. I think especially because some of the stuff that it did was in support of labor or like women reproductive justice. A lot of it was still very white led. So I think those were the moments that really I started to feel such just like, Wow, there is a lane for us to occupy. And in the midst of all this, learning about Yuri Kochiyama, Grace Lee Boggs, like reading their autobiographies, I started to see like, Wow, Asian America has roots in revolutionary activism. And just seeing that is sort of the world that I continue to exist in.

So I feel lucky that I've been in places where there have been existing communities and it was a space to grow politically, grow culturally, and then also start finding my own voice within some of that. And so yeah, right after college, living in New York, trying to rethink where I grew up through a more adult lens. Then I moved to Boston to go to grad school. That was my first foray into architecture and design and realizing how I had such a hard time. (laughs)

I mean, I thought I was talented and smart and then—I attended design school and realized, Oh, unless you are actually demonstrating proficiency in this one language of design and aesthetics, then you're actually not deemed talented at all. So I really struggled and so I veered. I found community in Boston, and it was rooted in the Asian diaspora.

So it's like the early 2000s—spoken word was like the thing; met poets there, ended up meeting an Asian American spoken word poet in Boston, and then just got actually connected to Asian American community there. And I think through two friends an Asian American artist collective turned into a community. I would say, like, the real education—not just my design education is what really transformed who I was. We created an Asian American open mic for us to create our own stories. One of our friends, his parents opened up a Chinese language bookstore that sort of closed down that we reopened to be an Asian American bookstore and sort of art space.

So really leaned into how do we create our own cultural center because a lot of it just wasn't focused on what it meant to be Asian American. So a few of our stories were out there. And so through the lens of I think primarily poetry is the first format of just speaking our truths in a safe space. That is really when I started to be like, This is home. This really is the place of possibility, but also like us building the world that we long for. So yeah, I think a lot of my identity—and I think the desire for community—has always been such a deep seeking out in this world. I feel so fortunate that there have been so many wonderful artists, cultural workers, community organizers that I've been able to learn from, collaborate with, but also really affirm and then also witness and see as role models.

So really understanding how important it is to just have a deep understanding of who you are and then in relationship to the world around you that's not designed for you. Then learning all those organizing skills in order to reimagine the spaces that we want. So, for me, that was architecture. Not the “How many permutations of a cube can we create on AutoCAD, or Illustrator, Rhino, whatever?” It really was cultural infrastructure in order to support our way of being that represents our cultural practices, our identity. That's to me, like, the architecture that I have, I think, now dedicated my whole practice to. So yeah, sorry, I'm going on and on. I'm like, reminiscing—I'm like, “Twenty years ago—”

TSC: That was an incredible story! I love hearing about your relationship to the identity Asian American and how you wove influences from your family and your mentors into that. I think a lot of people have almost moved in the opposite direction where they start off identifying as Asian American as a kind of default and now are slowly becoming more and more specific about what kind of Asian American they are. Whereas it's interesting to hear your experience of growing up very Corean and coming from a Corean family and then finding power in expanding out and coming into Asian American as a political identity.

I'm also curious about your sister! It sounds like she was a really big influence on your path. Do you think it has something to do with her being born in Corea? Did she grow up there for a little bit before coming over here? How did she even find or know about ethnic studies?

TH: I mean, she was like one and a half when she came over. But I do think there is something about—the physical place in which you're born has, like, cosmic implications on who you are. I don't know, it's like she found her own friends, went to, like, a small, tiny liberal arts college. But I do think a lot of the awarenesses my dad would bring up as it relates to injustice and then also recognizing we have a certain level of privilege, education—like, what are we doing in order to advocate for ourselves, but also work in our community? Both my parents were physicians and basically ran a community clinic that your entire family can get all of your health issues addressed—like adults and children in one place that spoke your language. So, in many ways, my parents, their practice was a bit of a community center of sorts. Everyone was like, Oh, I never knew that that was your mom! But I think in many ways both my mom and my dad have always framed it as like, What are we able to provide for our community? Because also our community is the one that keeps us safe in sort of today's terms.

So that was when I first started to attend public demonstrations—anti-war demonstrations. And then in those venues always joining either the people of color contingent, learning that people of color is also a very highly politicized intentional identity that people choose to opt into. But, also, I started again through my sister, who I've been so lucky to have like a great teacher to just show me so many different things, but also came into traditional Corean folk drumming. I mean, I'm sure you see now in protests the Corean drummers are always out in any type of demonstration. So that was a practice that I started to connect to sort of ancestral homelands, to agriculture, farm work, folk cultural traditions. But, also, it made me feel like I fit in or had a role in some of these demonstrations and just to show up in your full drumming garb and having a voice and then be surrounded by like, let's say, an Asian American contingent. It felt so powerful.

I think when I attended rallies in the past, I always felt still very marginalized. I think especially because some of the stuff that it did was in support of labor or like women reproductive justice. A lot of it was still very white led. So I think those were the moments that really I started to feel such just like, Wow, there is a lane for us to occupy. And in the midst of all this, learning about Yuri Kochiyama, Grace Lee Boggs, like reading their autobiographies, I started to see like, Wow, Asian America has roots in revolutionary activism. And just seeing that is sort of the world that I continue to exist in.

So I feel lucky that I've been in places where there have been existing communities and it was a space to grow politically, grow culturally, and then also start finding my own voice within some of that. And so yeah, right after college, living in New York, trying to rethink where I grew up through a more adult lens. Then I moved to Boston to go to grad school. That was my first foray into architecture and design and realizing how I had such a hard time. (laughs)

I mean, I thought I was talented and smart and then—I attended design school and realized, Oh, unless you are actually demonstrating proficiency in this one language of design and aesthetics, then you're actually not deemed talented at all. So I really struggled and so I veered. I found community in Boston, and it was rooted in the Asian diaspora.

So it's like the early 2000s—spoken word was like the thing; met poets there, ended up meeting an Asian American spoken word poet in Boston, and then just got actually connected to Asian American community there. And I think through two friends an Asian American artist collective turned into a community. I would say, like, the real education—not just my design education is what really transformed who I was. We created an Asian American open mic for us to create our own stories. One of our friends, his parents opened up a Chinese language bookstore that sort of closed down that we reopened to be an Asian American bookstore and sort of art space.

So really leaned into how do we create our own cultural center because a lot of it just wasn't focused on what it meant to be Asian American. So a few of our stories were out there. And so through the lens of I think primarily poetry is the first format of just speaking our truths in a safe space. That is really when I started to be like, This is home. This really is the place of possibility, but also like us building the world that we long for. So yeah, I think a lot of my identity—and I think the desire for community—has always been such a deep seeking out in this world. I feel so fortunate that there have been so many wonderful artists, cultural workers, community organizers that I've been able to learn from, collaborate with, but also really affirm and then also witness and see as role models.

So really understanding how important it is to just have a deep understanding of who you are and then in relationship to the world around you that's not designed for you. Then learning all those organizing skills in order to reimagine the spaces that we want. So, for me, that was architecture. Not the “How many permutations of a cube can we create on AutoCAD, or Illustrator, Rhino, whatever?” It really was cultural infrastructure in order to support our way of being that represents our cultural practices, our identity. That's to me, like, the architecture that I have, I think, now dedicated my whole practice to. So yeah, sorry, I'm going on and on. I'm like, reminiscing—I'm like, “Twenty years ago—”

TSC: That was an incredible story! I love hearing about your relationship to the identity Asian American and how you wove influences from your family and your mentors into that. I think a lot of people have almost moved in the opposite direction where they start off identifying as Asian American as a kind of default and now are slowly becoming more and more specific about what kind of Asian American they are. Whereas it's interesting to hear your experience of growing up very Corean and coming from a Corean family and then finding power in expanding out and coming into Asian American as a political identity.

I'm also curious about your sister! It sounds like she was a really big influence on your path. Do you think it has something to do with her being born in Corea? Did she grow up there for a little bit before coming over here? How did she even find or know about ethnic studies?

TH: I mean, she was like one and a half when she came over. But I do think there is something about—the physical place in which you're born has, like, cosmic implications on who you are. I don't know, it's like she found her own friends, went to, like, a small, tiny liberal arts college. But I do think a lot of the awarenesses my dad would bring up as it relates to injustice and then also recognizing we have a certain level of privilege, education—like, what are we doing in order to advocate for ourselves, but also work in our community? Both my parents were physicians and basically ran a community clinic that your entire family can get all of your health issues addressed—like adults and children in one place that spoke your language. So, in many ways, my parents, their practice was a bit of a community center of sorts. Everyone was like, Oh, I never knew that that was your mom! But I think in many ways both my mom and my dad have always framed it as like, What are we able to provide for our community? Because also our community is the one that keeps us safe in sort of today's terms.

“I'm choosing to be Asian American because I feel stronger being in relationship to all these other folks.”

Interview Segment: I’m choosing to be Asian American

So I think there was always sort of

like a consciousness around—there was never a deep individualism, I think. So I

think just naturally the things that we decided to learn, maybe that is what

resonated. I feel really lucky, and even when I went into architecture school,

it was always like, Yeah, because we need community centers for our people.

It's because we need housing for our people. Everything was always in the

framework of, like, collective resourcing as opposed to just individual

development.

And I think that's very Corean. It's very Asian where you think about your family. I think just beyond sort of like your immediate, whatever blood family, being able to stretch it as far as possible to your community. And yeah, I think it grew. It started off Corean, started Asian American. And I think it's really important a lot of my organizing work also centered my own needs. It was like, My stories aren't being told, so what is the space that I need in order to address it? So firsthand recognizing like, Oh, I'm being impacted in a certain way. What in our power can we do in order to sort of like transform the world around us?

So I think as I've gotten older—so those were my twenties, like really creating community spaces for Asian America. Like in my thirties when I moved to Los Angeles and I started to work in a community that I'm not having a firsthand lived experience. So I moved from Boston to LA to work with unhoused folks, and I landed in Skid Row to do this affordable housing fellowship. I'm working in a primarily Black community. So it's like I've never experienced being unhoused. There was a lot of sort of steps away from my own lived experience. But I think in many ways that's when I started to understand more deeply through an embodied practice what it meant to be a person of color and also recognizing sort of like the larger sense of solidarity in there. Because even though I didn't have direct experiences of homelessness, when I did work with community members, issues around substance abuse, mental illness, domestic violence, all of those issues were our own shared lived experiences that I've had. And just recognizing as communities of color, there are many through lines that we share.

So I think that's where I was able to embody what solidarity meant in terms of like, Yes, there is still shared understanding, right? Our experiences may not be exactly the same, but there is sort of the same systems that sort of produce some of these negative impacts—still touch us all as people of color. And so I think really that's when I started to understand more deeply the solidarity that you're not directly centered in, and how just recognizing your own then positionality of like, When do you need to step aside and sort of make sure other people's needs are being centered? That is a whole other, I think, level of relationship that needs nuanced understanding around.

But I do think I was able to sort of do that with depth because I went through a deep interrogation of what identity was for me. So I was able to sort of see what my adjacencies were, but also not trying to, like, co-opt. Not try to, like, play Oppression Olympics or anything like that. So yeah, I think the scaling up of affinity for me has been important and slow. I see my design work differently because I started off with sort of organizing for myself, designing for us, because I think it's different when some folks start off when you're like—you know, working in communities that you're brand new to, sometimes it could be more jarring or there could be more blind spots. So I think for me, the ability to deeply—and I'm still learning about Asian America. I think it continues to grow and as the generations also begin to age and our position in the US changes globally and layering on, just all those other contexts. It continues to be complicated. A lot of times our identity can be used as a wedge, and so it's tricky. I've always come from a place of like, Let's embrace it and just see where—I think just to be thankful to be a part of—have this lineage, I think to build off of.

TSC: I want to talk a little bit more about the solidarity aspect you talked about. I love that you said that you were scaling up in affinities. But that it also can be very nuanced when you're working with communities whose marginalized identities you may not hold. This is something that has come up in other interviews too, and I imagine you've dealt with like, How do you navigate bringing yourself to the work or not losing yourself in the work while centering other communities of color that you work with? Because I think oftentimes in white spaces we're used to assimilating or invisiblizing ourselves, but then in BIPOC spaces we tend to decenter ourselves. And I think that we can end up in the same position all the time in a way. I'm curious if you could share some more thoughts about that from your experiences of working.

TH: I think I'm still learning. I think I would say like in year four or five in the work I was doing in Skid Row is when I started to really see my role as just like, “Oh, I'm a space holder and a facilitator.” I think that's when I started to really embrace what that meant because—and that doesn't mean I'm a neutral party, but it sort of means like, You know what? This issue around housing for the most vulnerable is not about me. If anything, it's about connecting resources to the people that require it because they're the most impacted by the systems of oppression. But also making sure that sort of like the people allocating resources and making have all the decision-making power—also are able to be deeply informed by folks that are directly impacted.

And I think that's very Corean. It's very Asian where you think about your family. I think just beyond sort of like your immediate, whatever blood family, being able to stretch it as far as possible to your community. And yeah, I think it grew. It started off Corean, started Asian American. And I think it's really important a lot of my organizing work also centered my own needs. It was like, My stories aren't being told, so what is the space that I need in order to address it? So firsthand recognizing like, Oh, I'm being impacted in a certain way. What in our power can we do in order to sort of like transform the world around us?

So I think as I've gotten older—so those were my twenties, like really creating community spaces for Asian America. Like in my thirties when I moved to Los Angeles and I started to work in a community that I'm not having a firsthand lived experience. So I moved from Boston to LA to work with unhoused folks, and I landed in Skid Row to do this affordable housing fellowship. I'm working in a primarily Black community. So it's like I've never experienced being unhoused. There was a lot of sort of steps away from my own lived experience. But I think in many ways that's when I started to understand more deeply through an embodied practice what it meant to be a person of color and also recognizing sort of like the larger sense of solidarity in there. Because even though I didn't have direct experiences of homelessness, when I did work with community members, issues around substance abuse, mental illness, domestic violence, all of those issues were our own shared lived experiences that I've had. And just recognizing as communities of color, there are many through lines that we share.

So I think that's where I was able to embody what solidarity meant in terms of like, Yes, there is still shared understanding, right? Our experiences may not be exactly the same, but there is sort of the same systems that sort of produce some of these negative impacts—still touch us all as people of color. And so I think really that's when I started to understand more deeply the solidarity that you're not directly centered in, and how just recognizing your own then positionality of like, When do you need to step aside and sort of make sure other people's needs are being centered? That is a whole other, I think, level of relationship that needs nuanced understanding around.

But I do think I was able to sort of do that with depth because I went through a deep interrogation of what identity was for me. So I was able to sort of see what my adjacencies were, but also not trying to, like, co-opt. Not try to, like, play Oppression Olympics or anything like that. So yeah, I think the scaling up of affinity for me has been important and slow. I see my design work differently because I started off with sort of organizing for myself, designing for us, because I think it's different when some folks start off when you're like—you know, working in communities that you're brand new to, sometimes it could be more jarring or there could be more blind spots. So I think for me, the ability to deeply—and I'm still learning about Asian America. I think it continues to grow and as the generations also begin to age and our position in the US changes globally and layering on, just all those other contexts. It continues to be complicated. A lot of times our identity can be used as a wedge, and so it's tricky. I've always come from a place of like, Let's embrace it and just see where—I think just to be thankful to be a part of—have this lineage, I think to build off of.

TSC: I want to talk a little bit more about the solidarity aspect you talked about. I love that you said that you were scaling up in affinities. But that it also can be very nuanced when you're working with communities whose marginalized identities you may not hold. This is something that has come up in other interviews too, and I imagine you've dealt with like, How do you navigate bringing yourself to the work or not losing yourself in the work while centering other communities of color that you work with? Because I think oftentimes in white spaces we're used to assimilating or invisiblizing ourselves, but then in BIPOC spaces we tend to decenter ourselves. And I think that we can end up in the same position all the time in a way. I'm curious if you could share some more thoughts about that from your experiences of working.

TH: I think I'm still learning. I think I would say like in year four or five in the work I was doing in Skid Row is when I started to really see my role as just like, “Oh, I'm a space holder and a facilitator.” I think that's when I started to really embrace what that meant because—and that doesn't mean I'm a neutral party, but it sort of means like, You know what? This issue around housing for the most vulnerable is not about me. If anything, it's about connecting resources to the people that require it because they're the most impacted by the systems of oppression. But also making sure that sort of like the people allocating resources and making have all the decision-making power—also are able to be deeply informed by folks that are directly impacted.

“I feel really lucky, and

even when I went into architecture school, it was always like, Yeah, because we

need community centers for our people. It's because we need housing for our

people. Everything was always in the framework of, like, collective resourcing

as opposed to just individual development.”

Interview Segment: There was never a deep individualism

So I think it's one thing to decenter

yourself and then it's another thing to obscure yourself. And I think, yes, there are many times at meetings where I'm like,

Okay, this is the agenda. These are the folks that are going to be standing in

front of the room because, at this point, it shouldn't be me anymore. I will

buy the food and clean up afterwards and set up all the tables. But that's also

not necessarily me obscuring myself in that space. It's more about making sure

the people that can build the trust and the relationships necessary to get at

the root of—the heart of the matter are the ones given the space. But I also

recognize in the end like, I'm getting paid, right? So that's a form of not

being obscured. Whatever is produced, I'm going to have review process and decision-making

ability over it. So I think sometimes people just connect visibility with being

centered, and I think I've learned a lot that is also rooted in—I don't know—what

white-dominant culture deems as powerful. So I think there's always a balance

and it's intentional, I think, because I have a choice. Like, “Okay, well, I'm

going to make sure that these folks are the ones speaking.” I think that's

different.

I think when I am sitting in a table with just elected folks or policymakers, then yes, I'll make myself more visible in terms of speaking or showing face because I may be one of the few faces that aren't white in the room. But I think just sort of balancing what is appropriate in terms of, I think, how much space I take up, I think, is what it comes down to. Because in the end if we're talking about, like, designing solutions, I really should not be taking up that much space if we're talking about an issue that I'm not directly impacted by. I don’t know. This is all sort of roundabout.

TSC: You're blowing my mind. I love the distinction that you made between obscuring and decentering yourself and also almost using visibility and invisibility like a tool. Like when is it important to use your visibility versus invisibility towards the cause? I'm still ruminating, but I think it's really helping me reframe how I think about my own positionality. I'm also curious whether you've ever kind of experienced any resistance towards your role or presence in racial solidarity work as an Asian, as an East Asian, as a Corean person.

TH: Yeah, I mean, I remember in grad school going to sort of a students of color meeting. And I remember by the end of the year a lot of the folks were graduating and there was like a real, “What happens to this group?” Because it was founded by Black students. But in my head it wasn’t a Black student union; it was, like, students of color. And again, I came in with a framework of people of color being sort of like a larger umbrella for more folks to fit into. I remember people were like, Oh, well, should we change the name so that it could be more inclusive? And more inclusive always means, like, white folks can come in.

And I remember at some point I was like, “No, I think it's really important for there to be an explicit group that is supporting students of color, minority people, whatever you want to say.” And I remember getting pushback of like, “Well, when this was started this was for, like, real students of color.” And I think you hear that a lot sometimes of like, “You're Asian; you're a model minority.” Or people will use people of color when they really want to say Black. So I remember there was a pushback, but I also respected that. I was like, “They founded this,” and I was like, “If it was explicit that it was a Black-centered space, I would tread differently.”

I think when I am sitting in a table with just elected folks or policymakers, then yes, I'll make myself more visible in terms of speaking or showing face because I may be one of the few faces that aren't white in the room. But I think just sort of balancing what is appropriate in terms of, I think, how much space I take up, I think, is what it comes down to. Because in the end if we're talking about, like, designing solutions, I really should not be taking up that much space if we're talking about an issue that I'm not directly impacted by. I don’t know. This is all sort of roundabout.

TSC: You're blowing my mind. I love the distinction that you made between obscuring and decentering yourself and also almost using visibility and invisibility like a tool. Like when is it important to use your visibility versus invisibility towards the cause? I'm still ruminating, but I think it's really helping me reframe how I think about my own positionality. I'm also curious whether you've ever kind of experienced any resistance towards your role or presence in racial solidarity work as an Asian, as an East Asian, as a Corean person.

TH: Yeah, I mean, I remember in grad school going to sort of a students of color meeting. And I remember by the end of the year a lot of the folks were graduating and there was like a real, “What happens to this group?” Because it was founded by Black students. But in my head it wasn’t a Black student union; it was, like, students of color. And again, I came in with a framework of people of color being sort of like a larger umbrella for more folks to fit into. I remember people were like, Oh, well, should we change the name so that it could be more inclusive? And more inclusive always means, like, white folks can come in.

And I remember at some point I was like, “No, I think it's really important for there to be an explicit group that is supporting students of color, minority people, whatever you want to say.” And I remember getting pushback of like, “Well, when this was started this was for, like, real students of color.” And I think you hear that a lot sometimes of like, “You're Asian; you're a model minority.” Or people will use people of color when they really want to say Black. So I remember there was a pushback, but I also respected that. I was like, “They founded this,” and I was like, “If it was explicit that it was a Black-centered space, I would tread differently.”

“I think it's one thing to

decenter yourself and then it's another thing to obscure yourself.”

So also

this awareness that these identity names and labels are not always shared. Even

now it's, like, even more complicated. Like when you say BIPOC, what does that

mean? It's not always so intentional the words that people use and the

associations that you have with it. So I think there has always been a check. I'm like, Is this a Black-centered

space? Should I be here? It's like with any affinity space, Is this a queer-centered

space? Should I be here? What is my proximity? That's a question I ask myself allthe time. Like, what is the appropriate proximity to other folks in the room?

What is the desired closeness that we all want from each other?—but also making

sure that safety is in place and things like that. So even now when

going to some meetings or projects, there's just always, like, a check. Like,

Where's right for me? Even doing work in, let's say, like Little Tokyo that I'm

doing now. I recognize I'm not Japanese American, and there are many ways where

the historic JA community is centered. But then I go to a Black Lives Matter meeting,

and I know what it means to be, like, a non-black POC.

I feel fortunate there hasn't been a ton of pushback of like, “You shouldn't this, this, and that.” But I think I have tried really hard to—again, it comes down to, like, How much space should I be taking up? And I think that's some of the work that we all need to go through as it relates to racial justice and seeing where you are and thinking intersectionality as it relates to my own gender identity, my class, even just like longevity—like seniority, how long people have been associated with certain things. I think I've never been entitled to anything in this world, and I don't want to feel like anyone owes me anything. So it's something that I continue to grow, have more awarenesses around. But I definitely think it's really important to be mindful of. And then if you are corrected, to not be defensive about it or step out and make space for folks.

There are plenty of times when people are like, Oh no, not at all; it's actually really important—like you're able to pull in other resources that we're unable to. But I check; I will ask; I will, like, explicitly ask just to make sure that certain assumptions aren't being made. And so yeah, I think when I recognize I'm not the most impacted person in the room, like, what sensitivities do I need to hold in order to not perpetuate a dominant culture that may jeopardize a sense of safety or trust that's in the room?

TSC: Yeah. I think that's such a good point about always asking. Of course, there's the assuming that you belong, but there's also the assuming that people want you to kind of fade into the background. I think that can also come off as very presumptuous. I've been in a position where it has been the other way around where I've just assumed that people don't want me to co-author or co-present or put my name on something. And they've been like, Actually, no, you're part of this project; we want you here. But I think that the key is just asking and not assuming. So thank you for bringing that up.

I want to hear a little bit more about the projects you're working on. I know you've done a number of projects that directly address Asian American identity or history or experiences. I want to hear you talk a little bit more about what the experience is like working kind of with and for your communities, whether it's a Little Tokyo project you're doing now, or a project you've done in the past or another one you're working on.

I feel fortunate there hasn't been a ton of pushback of like, “You shouldn't this, this, and that.” But I think I have tried really hard to—again, it comes down to, like, How much space should I be taking up? And I think that's some of the work that we all need to go through as it relates to racial justice and seeing where you are and thinking intersectionality as it relates to my own gender identity, my class, even just like longevity—like seniority, how long people have been associated with certain things. I think I've never been entitled to anything in this world, and I don't want to feel like anyone owes me anything. So it's something that I continue to grow, have more awarenesses around. But I definitely think it's really important to be mindful of. And then if you are corrected, to not be defensive about it or step out and make space for folks.

There are plenty of times when people are like, Oh no, not at all; it's actually really important—like you're able to pull in other resources that we're unable to. But I check; I will ask; I will, like, explicitly ask just to make sure that certain assumptions aren't being made. And so yeah, I think when I recognize I'm not the most impacted person in the room, like, what sensitivities do I need to hold in order to not perpetuate a dominant culture that may jeopardize a sense of safety or trust that's in the room?

TSC: Yeah. I think that's such a good point about always asking. Of course, there's the assuming that you belong, but there's also the assuming that people want you to kind of fade into the background. I think that can also come off as very presumptuous. I've been in a position where it has been the other way around where I've just assumed that people don't want me to co-author or co-present or put my name on something. And they've been like, Actually, no, you're part of this project; we want you here. But I think that the key is just asking and not assuming. So thank you for bringing that up.

I want to hear a little bit more about the projects you're working on. I know you've done a number of projects that directly address Asian American identity or history or experiences. I want to hear you talk a little bit more about what the experience is like working kind of with and for your communities, whether it's a Little Tokyo project you're doing now, or a project you've done in the past or another one you're working on.

“Should I be here? What is my proximity? That's a question I ask myself all the time. Like, what is the appropriate proximity to other folks in the room? What is the desired closeness that we all want from each other, but also making sure that safety is in place and things like that.”

Interview Segment: What is the desired closeness we all want from each other?

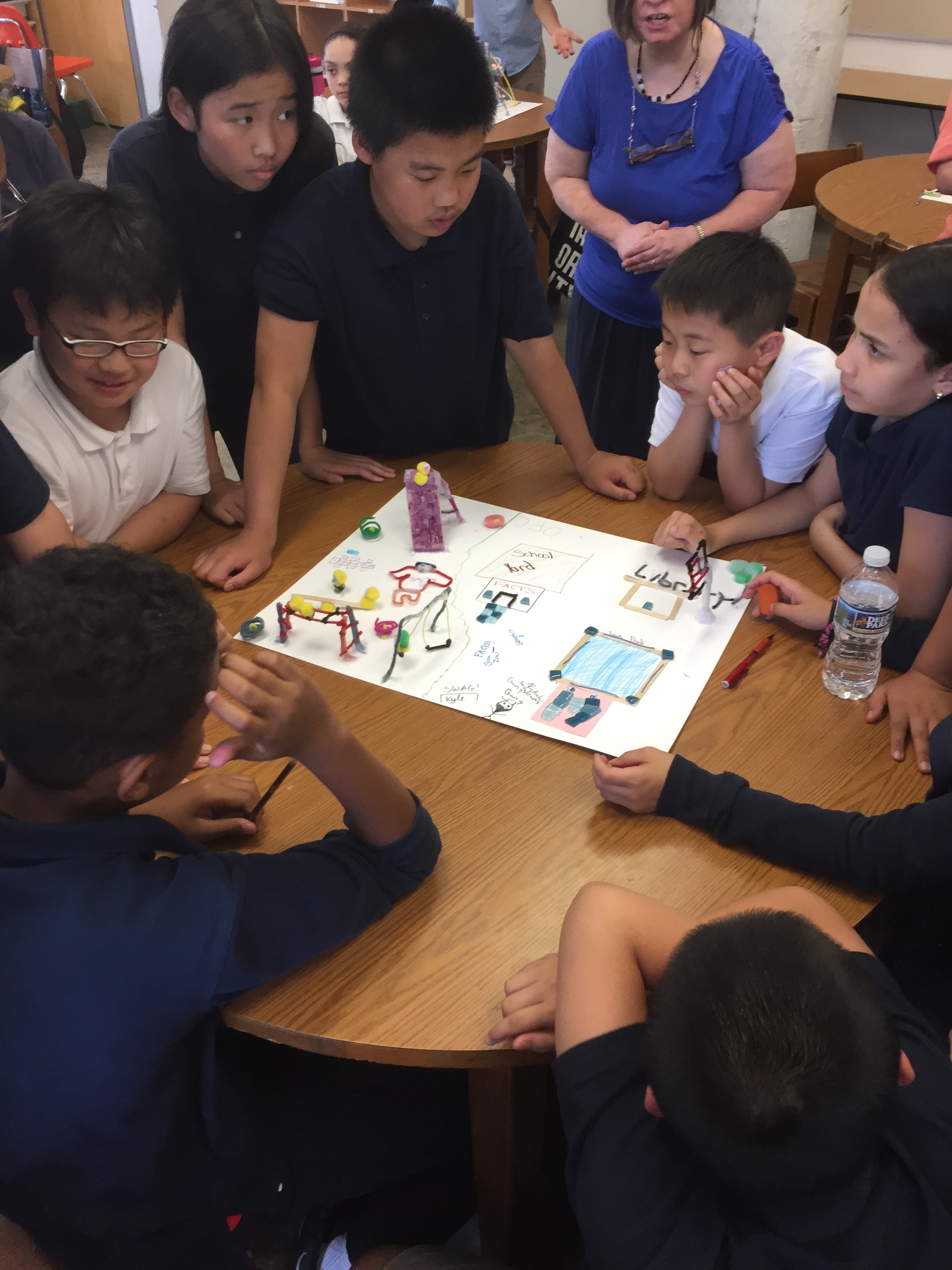

TH: It's interesting where—I think

the feeling of perpetually not belonging is part of the Asian American

identity. And a sense of just being very deferential to what's come before you.

So I've been working with Little Tokyo organizations—formally, I would say,

since like 2015. But really since I moved to LA in 2009, Little Tokyo has

always been—in many ways is this, like, storied center of Asian American

culture. It's like where East West Players was, like A Grain of Sand.

All these people that I read about, these are the public plazas; these are the

theaters. These are the stages that they stepped on. Even though it may center

the historic Japanese American experience, so much of it was to me about, like,

Asian American, especially like the cultural political center. I think it's,

like, what Oakland is to, like, the Black Panthers and Black power movement,

like, Little Tokyo was for me.

So there was always just sort of like—if there were meetings, I would just show up because, for me, this was, like, a place where—and I think other Chinatowns or other sort of diasporic ethnic neighborhoods have always been a place where I will have affinity for, even if it's not my ethnic background—like Chinatown or Little Saigon or places like that. So it just started off as like, I'm just going to go to certain meetings because I am an invested stakeholder. I want to see this community thrive. And it was through sort of like my other work in affordable housing that I met some of these other organizations. And when I sort of started my own practice, that was the opportunity to actually formally work together.

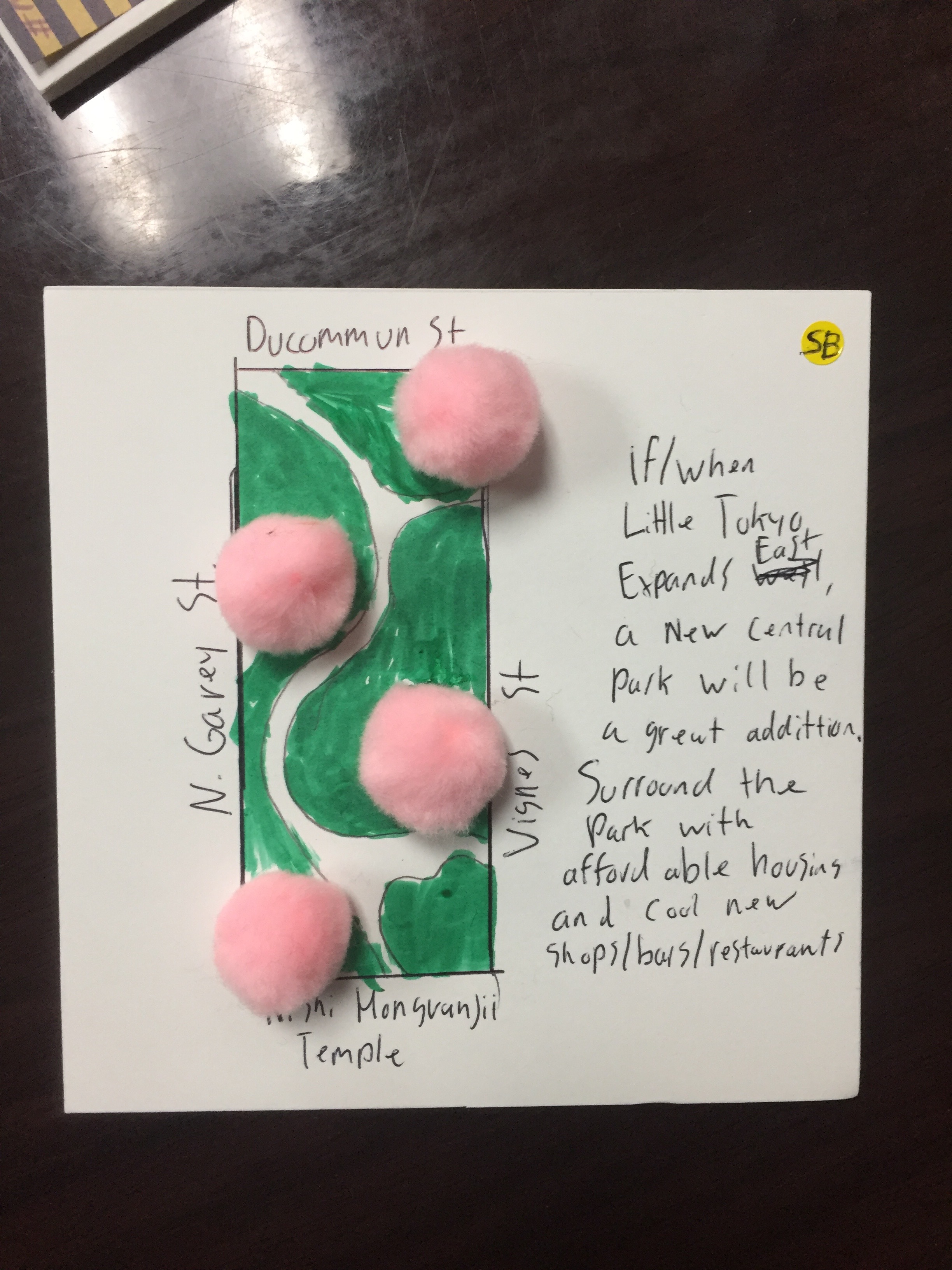

It's really wonderful where I'm working in a context of—again, thinking about what is the cultural infrastructure that reflects our people? I have as much buy-in because I want this for my child, for the next generations to come—and ensure that this space exists the same way. Like when I first came here in 2005, and I'm thinking about thirty years earlier of, like, these amazing cultural workers that fought to keep these places intact. So in many ways I see myself in it, but then when I hone in on the actual neighborhood politics, like with any community, my proximity is still further. There are always going to be people that are closest in terms of like, I don't live there; I don't work there every single day. And so again, it's like, How do you make sure you're honoring, respecting folks that have also, like, generations worth of labor invested into the community? But then also hearing, like, these are welcomed perspectives of sort of different leadership and also thinking about broader solidarity with other communities of color and recognizing Little Tokyo has the same struggle as Boyle Heights, as South Central, as other historic communities of color in Los Angeles. And how does what we are fighting for in Little Tokyo also then support the struggle in other neighborhoods.

So it's beautiful, but it's also so challenging when you're so personally invested in some of the work as well. And so, I've done a lot of things around thinking about a co-equitable neighborhood vision, and that changes even when you think about sort of like twenty years ago to now, sort of like the state of downtown has changed; the relationship to the unhoused community has completely changed. So how do the needs stay dynamic but then keep some of the cultural identity intact, but also create fluidity for things to change for the future—is also hard. I think in many ways I see some, let's say, historic Chinatowns. I still will have affinity for it, but also recognize what is permanent in terms of its aesthetics and in the buildings that are memorialized are from, let's say, like the early 1900s. Sometimes, like, a replication of that now becomes caricature. It's actually not representative of this complex, now fifth-generation Chinese diasporic identity that exists now. So I think some of it is also like we want to preserve legacy that's important, but we also need space for evolution because we want folks from, like, West Asia to feel affinity with Little Tokyo. We want biracial folks or other people who are even not Asian to feel affinity with the area.

But then if we just keep frozen certain aspects of what a neighborhood is supposed to look like, but also the functions and programs, I think, that also can get us a bit stuck because then we also want to think about addressing the larger issue of why certain ethnic communities are important to preserve—is because it is cultural resistance. It's like making sure that we have monumentalized places of permanence in still white-dominated spaces. So I continue to learn a lot, and it's always going to be complicated in terms of people don't want to change things, or some people want change faster. You can't meet everyone's needs all the time. And so, for me, the question comes down to equity and justice then. It's like in these areas, Who are the most impacted? Whose needs are never being met? Whose needs have been designed out? So it's like, What can we do then in order to center and redistribute attention, resources, decision-making in order to start addressing some of those needs. But then also recognize if we decenter certain needs that have maybe been centered in the past, it doesn't mean that it's not important. There's just maybe less urgency. And I think people need to not feel so scarce around that—actually recognize that actually means a lot of these needs are being met. That means, like, certain changes have actually happened. Now we can put time and attention in other areas in order to really think more holistically about certain things.

TSC: To build off of what you have been talking about, I wanted to hear a little bit about what your dreams and aspirations are for Asian diaspora spaces and also the people who are shaping them through design.

TH: I really want Asian America to be a proud choice. I don't want it to be sort of like a default association, or labeling, or someone else actually assigning it to you. I wish that people can see the strength of this shared experience that we do have in the US. And it's so complicated. We come from different cultures, different languages, all of this—like East Asian, Southeast Asian, Southwest Asia, we all even look different. It's such a wide range, but how exciting that could be if we also started to see the shared legacies and then being able to build all that power to actually address imperialism in ancestral homelands. Stuff like that can actually tear down some of the most violent systems of oppression that have been suffocating our countries and in the US for more generations than we can possibly remember.

So I think some of it is—don't just see it as, like, an ethnic association or just sort of the food that you eat. It really is a place of shared power and shared belonging in order to really transform the world that we live in. And how that also then fits into sort of like the larger system of oppression that also impacts and fuels anti-Blackness in our world and sort of larger impacts of racial capitalism and really thinking about if we all understood the power of our solidarity, it would be tremendous. And yeah, I think just to recognize to be Asian in the United States is an act of resistance. It is inherently political, like how we've all landed here and just wishing that people understood that or embraced that and understood that that was the legacy that we are a part of.

TSC: I share that dream as well. I want to hear a little bit about how you arrived at this place where you do feel this sense of pride. I think that a lot of Asian people may not think about it as a point of pride and see it more like a default or a fact or an ethnic association because of assimilation, survival, and shame from the way that we've been racialized, et cetera. And then also the fact that we can kind of slide by without thinking about it because of the model minority myth. So there's a combination of factors that within our own community results in a lot of people just kind of checking the box as a default and not thinking more about it. I'm very inspired by your story, and I'm also curious whether any of those elements seeped into your experience along the way or whether you kind of always felt very secure in your pride for your identity and wanting to share with others and bring others in.

So there was always just sort of like—if there were meetings, I would just show up because, for me, this was, like, a place where—and I think other Chinatowns or other sort of diasporic ethnic neighborhoods have always been a place where I will have affinity for, even if it's not my ethnic background—like Chinatown or Little Saigon or places like that. So it just started off as like, I'm just going to go to certain meetings because I am an invested stakeholder. I want to see this community thrive. And it was through sort of like my other work in affordable housing that I met some of these other organizations. And when I sort of started my own practice, that was the opportunity to actually formally work together.

It's really wonderful where I'm working in a context of—again, thinking about what is the cultural infrastructure that reflects our people? I have as much buy-in because I want this for my child, for the next generations to come—and ensure that this space exists the same way. Like when I first came here in 2005, and I'm thinking about thirty years earlier of, like, these amazing cultural workers that fought to keep these places intact. So in many ways I see myself in it, but then when I hone in on the actual neighborhood politics, like with any community, my proximity is still further. There are always going to be people that are closest in terms of like, I don't live there; I don't work there every single day. And so again, it's like, How do you make sure you're honoring, respecting folks that have also, like, generations worth of labor invested into the community? But then also hearing, like, these are welcomed perspectives of sort of different leadership and also thinking about broader solidarity with other communities of color and recognizing Little Tokyo has the same struggle as Boyle Heights, as South Central, as other historic communities of color in Los Angeles. And how does what we are fighting for in Little Tokyo also then support the struggle in other neighborhoods.

So it's beautiful, but it's also so challenging when you're so personally invested in some of the work as well. And so, I've done a lot of things around thinking about a co-equitable neighborhood vision, and that changes even when you think about sort of like twenty years ago to now, sort of like the state of downtown has changed; the relationship to the unhoused community has completely changed. So how do the needs stay dynamic but then keep some of the cultural identity intact, but also create fluidity for things to change for the future—is also hard. I think in many ways I see some, let's say, historic Chinatowns. I still will have affinity for it, but also recognize what is permanent in terms of its aesthetics and in the buildings that are memorialized are from, let's say, like the early 1900s. Sometimes, like, a replication of that now becomes caricature. It's actually not representative of this complex, now fifth-generation Chinese diasporic identity that exists now. So I think some of it is also like we want to preserve legacy that's important, but we also need space for evolution because we want folks from, like, West Asia to feel affinity with Little Tokyo. We want biracial folks or other people who are even not Asian to feel affinity with the area.

But then if we just keep frozen certain aspects of what a neighborhood is supposed to look like, but also the functions and programs, I think, that also can get us a bit stuck because then we also want to think about addressing the larger issue of why certain ethnic communities are important to preserve—is because it is cultural resistance. It's like making sure that we have monumentalized places of permanence in still white-dominated spaces. So I continue to learn a lot, and it's always going to be complicated in terms of people don't want to change things, or some people want change faster. You can't meet everyone's needs all the time. And so, for me, the question comes down to equity and justice then. It's like in these areas, Who are the most impacted? Whose needs are never being met? Whose needs have been designed out? So it's like, What can we do then in order to center and redistribute attention, resources, decision-making in order to start addressing some of those needs. But then also recognize if we decenter certain needs that have maybe been centered in the past, it doesn't mean that it's not important. There's just maybe less urgency. And I think people need to not feel so scarce around that—actually recognize that actually means a lot of these needs are being met. That means, like, certain changes have actually happened. Now we can put time and attention in other areas in order to really think more holistically about certain things.

TSC: To build off of what you have been talking about, I wanted to hear a little bit about what your dreams and aspirations are for Asian diaspora spaces and also the people who are shaping them through design.

TH: I really want Asian America to be a proud choice. I don't want it to be sort of like a default association, or labeling, or someone else actually assigning it to you. I wish that people can see the strength of this shared experience that we do have in the US. And it's so complicated. We come from different cultures, different languages, all of this—like East Asian, Southeast Asian, Southwest Asia, we all even look different. It's such a wide range, but how exciting that could be if we also started to see the shared legacies and then being able to build all that power to actually address imperialism in ancestral homelands. Stuff like that can actually tear down some of the most violent systems of oppression that have been suffocating our countries and in the US for more generations than we can possibly remember.

So I think some of it is—don't just see it as, like, an ethnic association or just sort of the food that you eat. It really is a place of shared power and shared belonging in order to really transform the world that we live in. And how that also then fits into sort of like the larger system of oppression that also impacts and fuels anti-Blackness in our world and sort of larger impacts of racial capitalism and really thinking about if we all understood the power of our solidarity, it would be tremendous. And yeah, I think just to recognize to be Asian in the United States is an act of resistance. It is inherently political, like how we've all landed here and just wishing that people understood that or embraced that and understood that that was the legacy that we are a part of.

TSC: I share that dream as well. I want to hear a little bit about how you arrived at this place where you do feel this sense of pride. I think that a lot of Asian people may not think about it as a point of pride and see it more like a default or a fact or an ethnic association because of assimilation, survival, and shame from the way that we've been racialized, et cetera. And then also the fact that we can kind of slide by without thinking about it because of the model minority myth. So there's a combination of factors that within our own community results in a lot of people just kind of checking the box as a default and not thinking more about it. I'm very inspired by your story, and I'm also curious whether any of those elements seeped into your experience along the way or whether you kind of always felt very secure in your pride for your identity and wanting to share with others and bring others in.

“It's interesting where—I think

the feeling of perpetually not belonging is part of the Asian American

identity. And a sense of just being very deferential to what's come before you.”

TH: I mean, I think

because there was an intense need to belong and recognizing the white and Black

binary of cultures, I inherently didn't belong. The cultural production of

second gen beyond Asian America was exciting, because then we can actually

design for ourselves. So I think for me then it looked in many ways like eating

rice cake soup and listening to Biggie on the radio at the same time. It meant celebrating

my ancestors, but then also recognizing that I have political ancestors that

aren't Corean on my altar. And I think it's this idea of, we don't need to

assimilate into whiteness in order to be accepted. We actually can be a part of

the creation of our own world. To me that was just very exciting, especially in

the moment that we are in. Yes, there are certain generations that have been

here for so long, but in many ways we do have the space to create this collective political identity and

it's always changing. Why not sort of opt into it and give it form, give it

visibility, instead of just being like, Mm-hmm, let me just continue to

choose which world to fit into?

TSC: An important component of this project or the kind of next phase of this project is to really create resources that'll be useful for Asian American designers and creatives. So I wanted to ask you what resources you would love to see for your fellow Asian American designers? Or what would you maybe have loved to see when you were younger and you were just getting into this field?

TH: I mean, I think some of it is happening in our generations. This question of, What is cultural infrastructure? What is an infrastructure that reflects the Asian American identity? I don't know. I think resources that support that—like resources that I wish existed or resources that I would point to?

TSC: I mean, you talk about wanting us all to think about our identity in this way where we see it as a political identity. And we see it as a way to belong, and build power, and work together towards better futures. I'm thinking of it like if you met an Asian designer and you were trying to direct them on this path, what resources do you think would be great for them to have? Is it like a book where you would say, “Here are some inspiring Asian designers to look at”? Or would it be something related to language? It could be anything. I'm wondering what you would need to feel supported in your work as an Asian designer working with and for other Asian communities.

TH: I mean, I think I would always just point folks to sort of the same books that I think politicized me. So it's like, read Living for Change, the autobiography of Grace Lee Boggs. First and foremost, see what it means to be Asian American, Asian in Black power movements. What does it mean to be in solidarity? What does it mean to be an activist? I think like reading Asian American pan-ethnicity and understanding that the creation of this identity is intentional and sort of some of the organizing from the sixties and seventies just to see the roots—to see the roots of what Pan-Asian solidarity looks like as just where we're from. I think it's like, okay, if you embrace this and you feel like okay—because it's also like learning your own political history.

We look at sort of like the Black power movement or the civil rights movement, the farm worker movement. There's so many other sort of national movements in the Black community, in the Latino community. And you don't realize that Asian America has deep, deep political roots as well. So it's like, first we need to just learn about that and recognize that. We're not just here to work quietly at our desks and fulfill capitalism.

TSC: An important component of this project or the kind of next phase of this project is to really create resources that'll be useful for Asian American designers and creatives. So I wanted to ask you what resources you would love to see for your fellow Asian American designers? Or what would you maybe have loved to see when you were younger and you were just getting into this field?

TH: I mean, I think some of it is happening in our generations. This question of, What is cultural infrastructure? What is an infrastructure that reflects the Asian American identity? I don't know. I think resources that support that—like resources that I wish existed or resources that I would point to?